Health Minister Rona Ambrose says she is "outraged" by the Supreme Court of Canada decision that expands the definition of medical marijuana beyond dried leaves, to include cannabis oils, teas, brownies and other forms of the drug.

In a unanimous decision Thursday, the Supreme Court ruled that users should not be restricted to only using the dried form of the drug. They said the current rules prevent people with a legitimate need for medical marijuana from choosing a method of ingestion that avoids the potential harms of smoking it.

But Ambrose says, despite recent court rulings in favour of the use of marijuana, her government maintains that cannabis has never been proven safe and effective as a medicine.

"Marijuana has never gone through the regulatory approval process at Health Canada, which requires rigorous safety reviews and clinical trials with scientific evidence," she told reporters in Ottawa.

"So frankly, I'm outraged by the Supreme Court."

She said Thursday's decision, as well as prior court rulings that permit the use of medical marijuana, give Canadians the impression that the drug has been shown to be effective, when it has not.

"We have this message that normalizes a drug where there is no clear clinical evidence that it is, quote-unquote, a medicine," she said, adding that never in Canada's history has a drug become a medicine "because judges deemed it so."

Currently, doctor-prescribed marijuana can only be offered in dried form; any other form could lead to charges under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

Medical marijuana advocates argued that for many patients, including the elderly, digesting the cannabis extracts was the only reasonable method of ingestion.

In a handful of cases, children like Liam McKnight will also benefit from these alternative methods of ingesting cannabis. The seven-year-old suffers from a rare form of epilepsy. Marijuana helps control the seizures.

For McKnight and children in similar situations, the Supreme Court’s ruling means they can have access to the medical benefits of cannabis without being putting their parents in the bizarre situation of encouraging their kids to smoke marijuana.

“I don’t think I’ve stopped crying since I found out,” said the boy’s mother, Mandy. “It’s just a huge, huge relief.”

The Supreme Court agreed with medical marijuana advocates that it was unreasonable to require users to smoke dried marijuana.

"Inhaling marihuana can present health risks and is less effective for some conditions than administration of cannabis derivatives," the court said in its judgment.

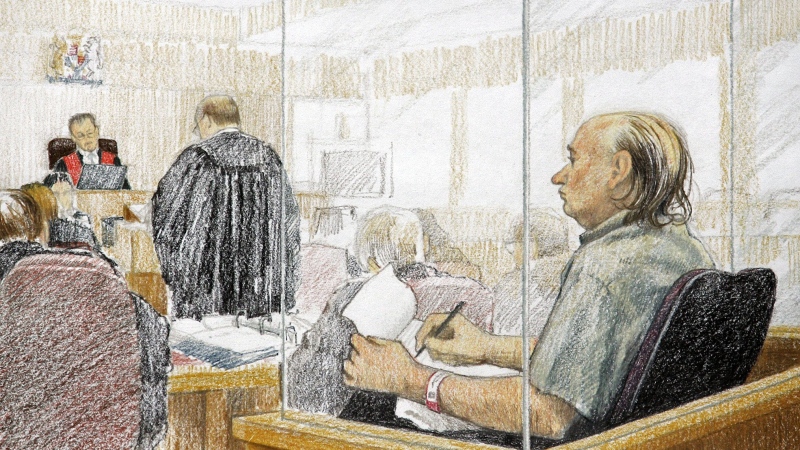

The case began in 2009, with the arrest of Owen Smith, the former head baker for the Cannabis Buyers Club of Canada. He was charged with unlawful possession of marijuana and possession for the purpose of trafficking, after police found large amounts of cannabis-infused olive oil and cookies in his apartment.

Smith challenged those laws, arguing that medical marijuana users should have the right to consume marijuana in other ways than smoking. The court agreed and Smith was acquitted at trial.

Last summer, the B.C. Appeal Court upheld that decision, and gave the federal government a year to change the Marihuana Medical Access Regulations to remove the word "dried" from its definition of marijuana.

The federal government, which does not endorse the use of marijuana, decided to challenge the decision in Canada's top court, where it contended there was not enough scientific evidence on the efficacy of "derivative cannabis products" such as baked goods, and argued that the Charter does not give medical marijuana users the right to obtain or produce drugs based on their subjective beliefs.

The Supreme Court disagreed.

"The evidence amply supports the trial judge’s conclusions on the benefits of alternative forms of marihuana treatment," it said.

"…There are cases where alternative forms of cannabis will be 'reasonably required' for the treatment of serious illnesses. In our view, in those circumstances, the criminalization of access to the treatment in question infringes liberty and security of the person."

Terry Roycroft of Medicinal Cannabis Resource Centre says the court decision is a significant one for medical marijuana users who didn't like smoking the drug. He says, when marijuana is smoked, its effects last a couple of hours, but when ingested the effects can persist for six to eight hours.

"There's much more medicine going in the body and you get much better results when you use an edible than when you use smoking," he told CTV News Channel.

The decision is also significant for doctors who worried about how to prescribe smoking marijuana, Roycroft added.

"When we start creating edibles, there is the possibility and there is the mechanism to standardize the dose, which is exactly what physicians want," he said.

Under the changed definition, marijuana can also be offered in the form of capsules, tinctures and ointments.

"The Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, one of their biggest concerns is the lack of standardization. So this … will allow them to be more accepting of this," he said.

Smith's lawyer, Kirk Tousaw, says while he is gratified by the ruling, he notes that Canada has failed to create a working system to allow patients to access medical cannabis and protect licensed growers.

"The government really has to go back to the drawing board here, start listening to patients and the people who understand the difficulties that patients are dealing with every day, and come up with a system that really protects those patients from the imposition of the criminal law," he told CTV News Channel from Vancouver.