SAN FRANCISCO -- Federal officials don't know how many migrant children they've sent to live with convicted criminals across the U.S. over the last three years, at a time the government sought to move young Central American migrants out of shelters and into private homes, says the chair of a bipartisan congressional subcommittee that meets Thursday on the issue.

Overwhelmed by the numbers of children crossing the border, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services weakened its child protection policies, leaving children vulnerable to human trafficking, Sen. Rob Portman said Wednesday in an opening statement to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

The subcommittee's hearing will examine weaknesses in the agency's placement program for migrant children, which Portman says suffers from "serious, systemic defects."

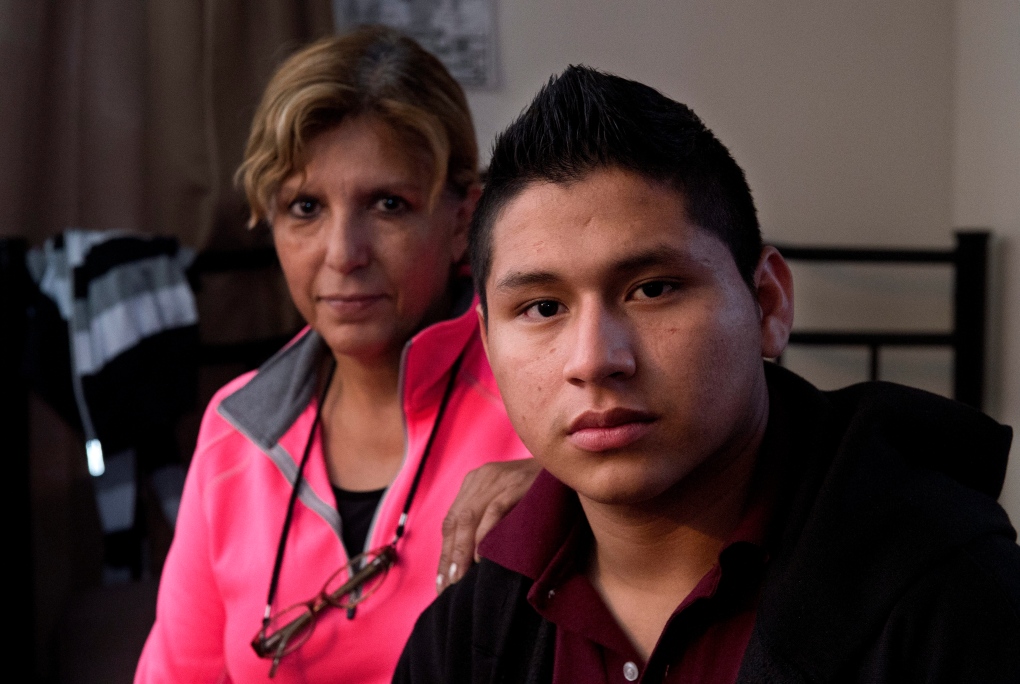

An Associated Press investigation released Monday found that more than two dozen unaccompanied children were sent to homes across the country where they were sexually assaulted, starved or forced to work for little or no pay.

In his statement, Portman said that as part of the subcommittee's six-month investigation, it reviewed "more than 30 cases involving serious indications of trafficking and abuse." Since almost all of the children have not been publicly identified, it could not immediately be determined if the children studied by the AP were among those cited by Portman.

"The program does an amazing job overall," HHS spokesman Mark Weber said in a recent AP interview. "We are not taking shortcuts."

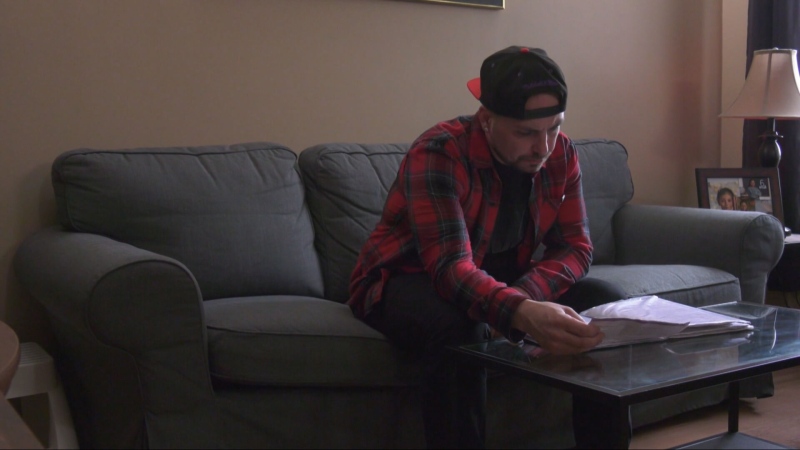

Top HHS officials are scheduled to testify at the hearing, which will reveal new details in a case in Portman's home state of Ohio, where six Guatemalan unaccompanied minors were placed with human traffickers including sponsors and their associates. Lured to the U.S. with the promise of an education, the teens instead were forced to work up to 12 hours a day on egg farms under threats of death.

"HHS told us that it is literally unable to figure out how many children it has placed with convicted felons, what crimes those individuals committed, or how that class of children are doing today," Portman said in a statement, noting that the agency changed its criminal background check policy only Monday.

HHS bars releasing children to anyone convicted of child abuse or neglect or violent felonies like homicide and rape. In November, Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa said a whistleblower contacted his office saying that unaccompanied children were placed with 3,400 sponsors who had criminal histories including homicide, child molestation, sexual assault and human trafficking. The government says it is investigating that claim.

HHS says it recently signed a contract to open new shelters, and is strengthening its protection procedures as the number of young migrants is once again rising.

According to emails, agency memos and operations manuals obtained by AP, some under the Freedom of Information Act, the agency relaxed its procedures as the number of young migrants rose in response to spiraling gang and drug violence in Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.

First, the government stopped fingerprinting most adults seeking to claim the children. In April 2014, the agency stopped requiring original copies of birth certificates to prove most sponsors' identities. The next month, it decided not to complete forms that request sponsors' personal and identifying information before sending many of the children to sponsors' homes. Then, it eliminated FBI criminal history checks for many sponsors.

AP uncovered accounts of children placed with sponsors who forced them to work taking care of other children and in cantinas where women drink, dance and sometimes have sex with patrons. Other teens were placed with relatives who were abusive and locked them inside the home. Experts who work with migrant children, including a psychologist and an attorney, cited cases in which unaccompanied children were raped by relatives or other people associated with their sponsors.

Advocates say it is hard to gauge the total number of children exposed to dangerous conditions among the more than 89,000 placed with sponsors since October 2013 because many of the migrants designated for follow-up were nowhere to be found when social workers tried to reach them.