BANGUI -- France and the African Union on Saturday announced plans to deploy several thousand more troops into embattled Central African Republic, as thousands of Christians fearing reprisal attacks sought refuge from the Muslim former rebels who now control the country after days of violence left nearly 400 people dead -- and possibly more.

French armoured personnel carriers and troops from an AU-backed peacekeeping mission roared at high speed down Bangui's major roads, as families carrying palm fronds pushed coffins in carts on the road's shoulder. In a sign of the mounting tensions, others walking briskly on the streets carried bow-and-arrows and machetes.

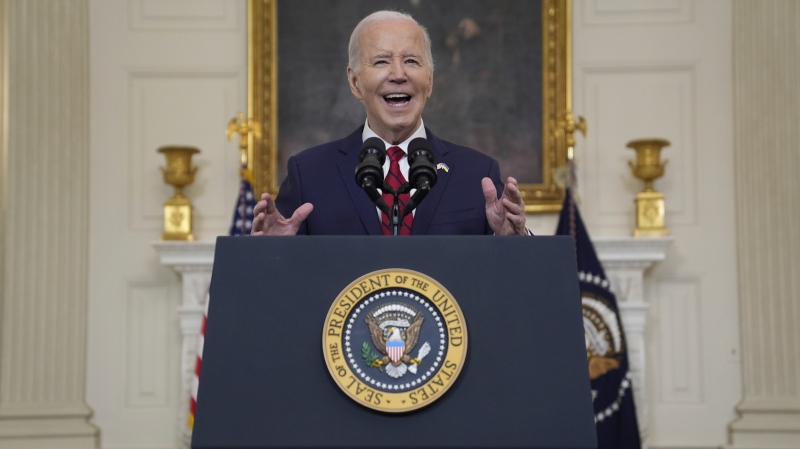

Concluding an aptly-timed and long-planned conference on African security in Paris, President Francois Hollande said France was raising its deployment to 1,600 on Saturday -- 400 more than first announced. Later, after a meeting of regional nations about Central African Republic, his office said that African Union nations agreed to increase their total deployment to 6,000 -- up from about 2,500 now, and nearly double the projected rollout of 3,600 by year-end.

Amid new massacres on Thursday, U.N. Security Council adopted a resolution that allows for a more muscular international effort to quell months or unrest in the country. Troops from France, the country's former colonial overseer, were patrolling roads in Bangui and fanning out into the troubled northwest on Saturday.

"This force is going to deploy as quickly as possible and everywhere there are risks for the population, with the African forces that are present -- currently 2,500 soldiers," Hollande said, referring to the increased French presence. "In what I believe will be a very short period we will be able to stop all exactions and massacres."

In an interview with France-24 TV, Hollande specified the AU reinforcements would arrive "in the coming days."

Word of the bigger deployments came as human rights groups continued the grisly business of counting and collecting bodies of those killed in recent massacres. The death toll in the capital from the recent fighting rose on Saturday to 394, said Antoine Mbao Bogo of the local Red Cross.

Meanwhile, Central African Republic's president called on the former rebels who are now integrated into the national army to stay off the streets now being patrolled by French and regional forces. Presidential spokesman Guy Simplice Kodegue said those who violated the order would be punished.

Aid workers returned to the streets to collect bloated bodies that had lay uncollected in the heat since Thursday, when Christian fighters known as the anti-balaka who oppose the country's ruler descended on the capital in a co-ordinated attack on several mostly Muslim neighbourhoods.

Residents of Christian neighbourhoods said the ex-rebels known as Seleka later carried out reprisal attacks, going house-to-house in search of alleged combatants and firing at civilians who merely strayed into the wrong part of town.

Zumbeti Thierry Tresor, 23, was among those slain after he tried to cross through another neighbourhood to visit family members in another part of Bangui. Seleka fighters shot him in the neck and stomach, his friends said. On Saturday, neighbours hiked the rocky path to his one-room home where his covered body lay on the floor underneath neatly hung music posters.

Outside the front door, his wife wailed hysterically, gripping their 3-year-old daughter in her lap as neighbours crowded around her. Alongside their house, a team of a dozen men with sticks and shovels dug Tresor's grave under the shade of a tree.

"We want the French army to come and protect us," said Tresor's friend, Francois Yayi. "We have no police to call. The Seleka will kill us all."

He and his friends begin counting on their fingers the number of neighbours slain amid the latest spasm of bloodshed. At least 10 they determine have died since Thursday.

As families mourned their dead, others fled by the thousands to the few known safe places in the capital -- the airport guarded by French troops and the grounds of a Catholic centre run by the Salesians of Don Bosco. About 3,000 people had fled to the complex on Thursday when the fighting began and that number swelled to 12,000 by Saturday.

"We have no water, no food, no medicine -- we have nothing," said Pierre Claver Agbetiafan, looking around the centre where he works.

As dusk fell, hundreds of people began lining up outside the mission's doors for a safe place to sleep, carting foam mattresses and plastic buckets of food on their heads. Some even toted wheeled luggage, not knowing when they could return. Every bit of ground near the tennis courts was crowded with families preparing for a night on damp ground under the open sky. The air filled with smoke as women tended small fires to prepare dinner.

Judith Lea, 47, came with a family of 20 including her 3-day-old grandson to escape violence in their neighbourhood on the north side of the capital. As people settled in for the night, she and the other female relatives argued over what to name the little boy who has spent nearly his entire life in a displacement camp.

"When the Seleka rebels came to the house, they stole his blankets and all the little things we had bought for him," Lea said, stretched out on the ground to rest. "When this war is over, what will we do? He is cold and hasn't had his vaccines yet."

Most of the displaced in Central African Republic's capital are Christian, as the ex-Seleka have not targeted Muslim neighbourhoods. However, anger over the Seleka attacks has prompted vicious reprisals on Muslim civilians in other parts of the country. Nearly a dozen Muslim women and children were slain less than a week ago just outside the capital in an attack blamed on the Christian fighters.

Central African Republic, one of the world's poorest countries, has been wracked for decades by coups and rebellions. In March, the Muslim rebel alliance known as Seleka overthrew the Christian president of a decade. At the time, religious ideology played little role in their power grab. The rebels soon installed their leader Michel Djotodia as president though he exerted little control over forces on the ground.

The rebels are blamed for scores of atrocities since taking power, tying civilians together and throwing them off bridges to drown and burning entire villages to the ground. Anger over the Seleka abuses translated into a backlash against Muslim civilians, who make up only about 15 per cent of the population.

An armed Christian movement has arisen in response to the Seleka attacks, and it is widely believed to be supported by former members of the national army loyal to ousted President Francois Bozize.