Chrissy Brajcic was once a healthy, happily married mom of two boys, with a thriving interior design business. But she became house bound and bed-ridden, battling constant infections and chronic pain after getting a mesh implant to treat a common female disorder.

When she died in late November 2017, her case made international news and raised questions about the safety of plastic mesh, a product that was already under intense scrutiny.

It began innocently enough. Chrissy had stress urinary incontinence (SUI) -- trouble controlling urine -- which began after giving birth to her second child.

Her doctor recommended treatment with a mesh sling -- a product made from a long narrow strip of polypropylene, a type of plastic. It is designed like a hammock, to support the urethra -- the tube connecting the bladder to the outside of the body.

He described the operation as simple and low risk, Chrissy said. But within hours of her mesh surgery, she knew something was wrong.

“The pain got worse and worse and worse, and finally it was like my insides were ripping out, I couldn't pee hardly at all,” she told W5.

Chrissy said it took over a year to find a doctor skilled enough to remove the mesh. The implant is designed to be permanent and hers had to be extracted, piece by piece, in a five-hour procedure.

Even when the implant was finally gone, Chrissy said she was still in pain.

“Once they took the mesh out, it caused so much trauma ... my pelvic floor is now collapsing and falling out,” she said.

She has chronic infections and pain from nerve damage that sends her to hospital nearly once a month.

"I can’t walk, I can’t take my kids to the park. Every little thing I do is such a huge ordeal to even get myself out of the house,” she told W5, in tears.

“[I feel] anger that my life was taken away from me and my kids.”

Just four months after Chrissy’s interview with W5 she was re-admitted to hospital where she battled infection and, finally, sepsis. She died a few weeks later. Chrissy was only 42 years old.

However, the coroner has not confirmed her cause of death and her family is awaiting the results of a toxicology examination. It is unclear if surgical mesh implant is to blame.

News of her sudden death devastated the close-knit community of mesh patients worldwide – many who followed Brajcic’s painful journey on social media.

Kath Sansom, who launched the U.K. patient support group Sling the Mesh after she suffered severe pain in her legs following her own mesh surgery in 2015, said: “What is so heartbreaking is to see that Chrissie, like all of us, trusted her surgeon when she was told it was a simple fix. She went for it because why wouldn’t you? Great, it’s a day case. This is a really good fix for my problem.”

“And, and she’s died from that? I think we all struggle to get our head around the fact that Chrissie’s death was so … unnecessary.”

In Canada, there are thousands of women registered as part of class action lawsuits or filing their own cases against the makers of pelvic mesh devices, claiming the products caused irreparable harm.

In the U.S., patients have filed over 100,000 cases against several companies like CR Bard, AMS, Boston Scientific, Johnson& Johnson and its subsidiary, Ethicon.

Mesh history

The lawsuits and controversy are just the latest development in a saga that began over 15 years ago.

The first female pelvic products for SUI came on the market in the 1990s . By the early 2000s, mesh makers had also developed transvaginal kits to treat a condition called pelvic organ prolapse (POP) –where the muscles that hold pelvic organs in place become weak from childbirth or age.

Companies marketed their implants as a quicker and easier way of fixing both conditions. Doctors could perform the procedure in under an hour, using minimally-invasive surgery.

Patients could go home the same day -- a big advantage over traditional repair which used a woman’s own abdominal tissue and involved long surgeries and recoveries.

However, in 2008, the news started to shift.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a safety warning, indicating that “rare” complications -- including pain, tissue erosion, infection, and painful intercourse -- were associated with transvaginal mesh used to treat SUI and POP.

In Canada, there were similar advisories in 2010 and 2014, with officials stating doctors should inform patients of the risks before they undergo surgery.

In the U.K., injured women are becoming more vocal -- holding protests in front of parliament in London, determined to bring a hidden problem into the public eye.

“There are women in wheelchairs or walking with sticks because of this operation. Others with life-altering chronic pain, on cocktails of high dose medication. Many can no longer work, marriages have broken down and all for a 20-minute, day case operation that was supposed to improve their quality of life,“ said Sansom. Her group is calling for investigations to find out how many U.K. women are affected and how the mesh products were approved.

Some governments are listening. The UK and Scotland have launched studies to assess how many patients have been harmed. Australia and New Zealand went further, banning some mesh products for organ prolapse, calling them too risky.

And this month the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence is calling for more research, particularly based on how patients are selected and long term impact of this procedure on patients.

The anti- mesh movement is gaining momentum, said Sansom.

“It is … as big, if not bigger, than the thalidomide scandal and it needs to stop before more women are maimed unnecessarily,” she said.

Hernia mesh

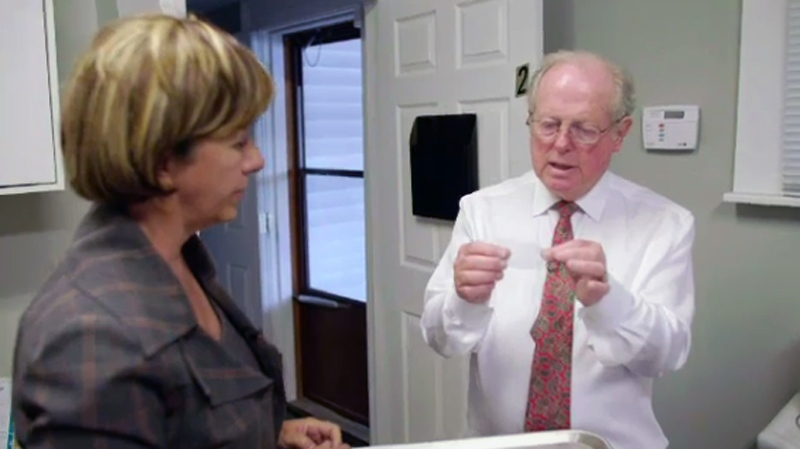

Some doctors are starting to question hernia mesh -- a product used in about 100,000 hernia repairs in Canada every year. It is the standard of care, according to most surgical advisory groups. But surgeon John Morrison warns he’s seeing hernia mesh cause serious problems..

“I've seen hernia mesh erode into the adjacent tissues, the tissue that's beside it. I've seen mesh erode into …. the spermatic cord. I've had ... patients with the mesh erode into the rectum and actually hang out through the anal canal," Dr. Morrison told W5 from his clinic in Chatham, Ont.

Dr. Morrison is performing more mesh removals and receives calls from across Canada from patients desperate for help.

“They feel that nobody will listen to them. And that is the most striking feature of all, that they are getting passed from one professional to another to another," he said.

Twenty-six-year-old Keith Richter says his hernia mesh implants caused severe pain that prevented him from playing hockey and going skateboarding -- activities he loves. It made him feel “useless”

“It sucks,” he said, wiping away tears. He recently got his implant removed and joined a class action lawsuit against C R Bard and Bard Canada, the maker of his implant.

Mesh under the microscope

While the battle heats up in court, one doctor is studying mesh in the lab to uncover why some patients experience problems.

Dr. Vladimir Iakovlev is the director of Cytopathology at St. Michael’s hospital. He has examined over 500 specimens removed from patients experiencing complications.

The products are implanted flat, but in the body they can fold up and shrink -- sometimes up to 50 per cent of their original size, he said.

His examination confirmed nerves, blood vessels and scar tissue have grown into the mesh fibres – “like a rebar in concrete.” He said this makes the product difficult to remove and can cause pain in some patients.

When he examines a sample under a microscope, he can see that mesh sometimes moves from the site of repair to puncture surrounding tissues like the bowel or the vagina.

"I find that almost all meshes moves. Some mesh move just microns, very little, some mesh move all the way through the bowel,” he said.

These complications happen in only a fraction of patients, he said, but often enough to worry him. He said the polypropylene mesh degrades and becomes brittle over time in the body.

He said we need more studies to understand long-term risks.

The debate over mesh also raises questions about how these mesh products were initially approved.

In most countries, including Canada, new medical devices get quick approvals if they are similar to medical devices already on the market -- a common procedure called “substantial equivalence.”

Critics claim that stricter human testing should be required for all medical devices before they are sold on the open market.

Many patients are demanding registries to track all implanted medical devices so that problems can be identified quickly.

Doctors: Mesh is a valuable tool being maligned

Across North America there are surgeons who specialize in hernias and in female pelvic disorders who steadfastly believe that mesh is an important tool. They say negative press around the world is giving mesh a bad name and scaring patients from a product that might help them.

“If you come to one of our clinics and talk to most of the patients that I see, they're overjoyed and thrilled with the experience that they've had with mesh fixing their problems,” said Dr. Colleen McDermott, a urogynecologist based in Toronto who uses mesh regularly to treat incontinence.

“Unfortunately there's no media coverage about that, right? Because people who are happy don't usually talk about it," she told W5.

One patient she treated “could not leave her house because she was just constantly, just constantly wet and changing pads and changing Depends and undergarments because she was soaked all the time. ... We cured her.“

But not all doctors have the experience or skill to perform these procedures, and Dr. McDermott wonders if this is partially to blame for complications some patients are experiencing worldwide.

In the early 2000s, "the companies that were producing these devices were targeting the generalists to do them and inviting them down to do these 3 or 4 day courses somewhere nice and learn how to do them. And then these physicians were going back to their practice and doing a lot of them because they’re quick, can have an easy patient turnover, usually patients go home the same day,” said Dr. McDermott, who received three years of specialized training to implant mesh.

“The problem is that you can't learn how to do these procedures in 4 days.”

Dr. David Urbach, surgeon‐in‐chief at Women's College Hospital, said he uses mesh in virtually all hernia repairs.

He believes complications for pain and other problems are rare – one to two per cent. But with so many hernia mesh repairs done every year, it means about 1,000 to 2,000 people could end up with complications and chronic pain.

“That may seem like a huge problem, and it is a problem to people who are personally affected, but it’s really a consequence of the fact that this is such a common procedure, even if the risk of severe problems is quite low,” he explained.

“No one's arguing that hernia repair is perfect, or that mesh repairs are perfect, but we think on balance, that the risks of using mesh repairs are outweighed by the benefits of mesh repairs.”

He and Dr. McDermott stressed the need for informed consent so patients are made well aware of the risks as well as the benefits.

McDermott spends 45 minutes reviewing options other than mesh -- like laser therapy or physiotherapy. Though she said often these treatments can cost thousands of dollars and may be out of reach for many patients.

She is also very careful not to offer mesh to patients who have a higher risk of complication -- such as women with fibromyalgia, autoimmune diseases or any history of chronic pain.

Questions remain

The Canadian Institute for Health Information data shows that in 2016, 972 people had pelvic mesh removed -- that’s almost three removals a day.

Considering these are permanent devices, the removal rates beg research into why.

Dr. Morrison himself is removing several a month. He wonders if mesh is offered too often for hernia repair. There are studies that suggest that younger patients and smokers are at higher risk for post-operative pain.

He also said patients can explore alternatives like getting hernias repaired using their own tissue. The Shouldice Hospital in Thornhill, Ont.,which specializes in hernia repairs, does not use mesh -- with studies showing low complication rates and low hernia recurrences.

"I am not against mesh. I am against the absolute use of mesh in every case. I would much prefer a surgeon to say: ‘Hey, do we actually need to use mesh in this position? Does this patient require mesh?’ … It may save them major grief years down the road,” Dr. Morrison said.

The numbers

- There are some 25,000 surgeries to treat stress urinary incontinence done annually in Canada; about 90 per cent with mesh

- There are approximately 100,000 hernia repairs in Canada, over 90 per cent with mesh

- Studies on mesh complications have been quite mixed -- ranging from 1 to 2 per cent for SUI to 15 percent and higher for POP.

Lawsuits

In the U.S. there have been several large settlements in female pelvic mesh lawsuits. Some woman in Canada have settled with mesh makers quietly. The exact terms of settlements were not publicly disclosed.

In 2016 Bard Canada, the makers of Avaulta, Align, and Adjust brands of transvaginal mesh, agreed to pay some $2.4 million to settle claims against three products: Avaulta, Align, and Adjust. There were 30 eligible Primary Claimants. After legal costs they received about $60,000 in compensation.

ADVISORIES ON SURGICAL MESH:

- 2008 U.S. Food and Drug Administration public health notification about vaginal mesh

- 2010 Health Canada Advisory on complications associated with transvaginal implantation of surgical mesh

- 2014 Health Canada's notice to hospitals

- 2014 Heatlh Canada notice on what to do if considering or have had a mesh implant

More resources

NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA BAN SOME MESH PRODUCTS

CANADIAN UROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION POSITION STATEMENT

STRESS URINARY INCONTINENCE (SUI)

In 2016, the Canadian Urological Association issued a position statement stating that the medical literature supports the use of mesh sling to treat SUI and that complications rates are low. However, surgeons performing these procedures should be well trained and be able to deal with complications should they arise. Also, patients should be told of the risk and benefits before they consent to surgery.

PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE (POP)

The Canadian Urological Association says the medical literature does not support the routine use of transvaginal mesh for prolapse repair.

It is a position supported by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the British Society of Urogynaecology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

However, the American Urogynecologic Society UAS stresses there is an important role for the selective use of mesh for POP.

Since the federal Food and Drug Administration updated their warning in 2011, surgical mesh used for POP repair has been reclassified as a high risk device and one that requires more stringent approval than before.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE (NICE)

The NIHCE published new guidelines stating there is not sufficient evidence on the safety of laparoscopic mesh procedures for organ prolapse

Our W5 investigation MESH MISGIVINGS airs Saturday at 7 p.m. EDT on CTV.