Ontario's McMaster University says it can produce four times the amount of medical isotopes as the failing Chalk River reactor, in a possible solution to a severe worldwide shortage.

"Our physicists have done the calculations and verified them with the literature and . . . that equals, at the end of the day, 20 per cent of the North American market," Christopher Heysel, McMaster's director of nuclear operations and facilities, told a House of Commons committee on Tuesday.

But the school would need $30 million in government funding over the next five years. It has already received $22 million from both the federal and Ontario governments.

McMaster's 50-year-old reactor is the only other Canadian facility that can produce Technetium-99m (Tc-99m), the principal medical isotope used in cancer tests. It once filled in for the Chalk River reactor in the 1970s during a shutdown.

Meanwhile, the federal government announced $6 million to fund research into alternatives to Tc-99m, which is produced from molybdenum-99 (Moly-99).

With the reactor shutdown expected to last three months or longer, medical imaging experts have been struggling to meet the needs of patients requiring important diagnostic images.

Just this week, nuclear medicine leaders, meeting in Toronto, called for legislators to fund more research so they can shift dependence away from the commonly used Tc-99m.

"Through this funding, we hope to research into alternative, non-nuclear isotopes that could supplement or replace Tc-99m in certain medical imaging procedures," Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq said.

"We will also support the production of these alternatives to reduce the time it takes to move to clinical trials."

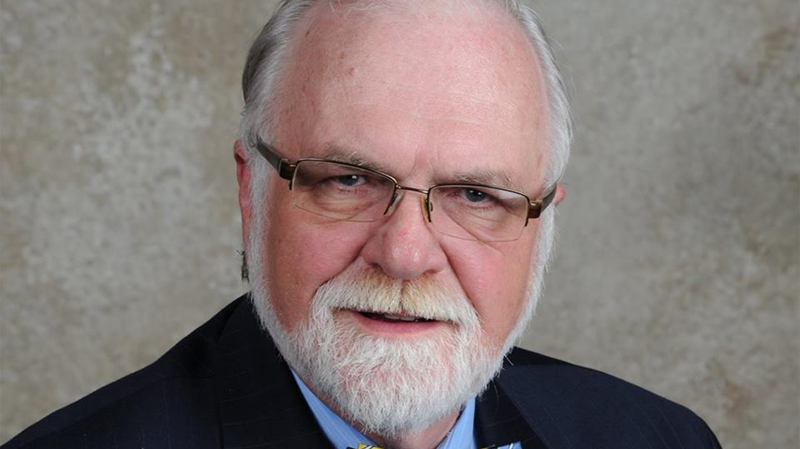

The president of the Society of Nuclear Medicine, Dr. Robert Atcher, is saying the long-term solution to the worldwide isotope shortages isn't necessarily in building new reactors.

"It turns out that our real problem isn't that there aren't enough reactors to make medical isotopes," Atcher told CTV on Tuesday.

"It's the production facilities that we use when we take those targets out of the reactor and process them to remove the medically useful isotopes -- that capacity around the world is very limited. So we don't need necessarily to build any more reactors; we need to build those processing facilities."

The nuclear medicine conference, usually a forum for celebrating new ways of diagnosing disease, is being dominated by the Chalk River shutdown, which Atcher says has caused two problems.

"One is that we've lost a third of our capacity. But the second point is that the Canadian reactor is also responsible for making up about 25 per cent of capacity if any of the other four reactors around the world go offline," he explained.

"So, for example, the reactor in the Netherlands is scheduled to go down in July, and with Chalk River offline, we won't be able to make up for that reactor not producing as well."

Facilities that are too old

There are only five countries with reactors that produce the raw materials for medical isotopes: Belgium, Canada, France, the Netherlands and South Africa. Each of those reactors has been operating for about five decades.

Atcher says it's clear that too many demands are being placed on too few facilities that are simply too old.

"It's really too bad that we had to face this, but on the other hand, the reactor at Chalk River is at the end of its useful life. So we anticipated that it would go offline in the next few years," he said.

Atcher added that the announcement last week from Prime Minister Stephen Harper that Canada will get out of the medical isotope business when the 52-year-old NRU reactor finally is mothballed (likely by 2016), helps nuclear medicine organizers to plan for the future.

"There's a silver lining in that now we know when Canada is planning to cease activity. So that gives us a deadline to develop more capacity and to potentially even build a new reactor that might take over," Atcher said.

Canada had been planning to have two reactors dedicated to producing medical isotopes by now. AECL was building two reactors at Chalk River -- the Maple project -- that were supposed to be operating by 2000. But after 12 years of development and cost overruns, the reactors never worked well enough to be put into commercial production. AECL concluded last year that the Maple project would have to be cancelled altogether.

Health Canada also has a stopgap, announcing late Monday a new source for Tc-99m.

It said it has authorized Lantheus Medical Imaging of Boston, Mass. to use Moly-99 produced by the Open Pool Australian Light-water (OPAL) reactor to make Tc-99m for Canadian health care facilities.

Health Canada's approval means that the Moly-99 produced by the OPAL reactor is safe and effective for use by Canadian health care providers.

"This is very good news for Canadian health care providers and patients," Aglukkaq said in a news release.

In the meantime, with diagnostic tests being delayed or cancelled, deaths are possible, warns Atcher, because there is little capability to use other imaging technologies in many kinds of diagnosis.

"For patients with lung cancer, prostate and breast cancer, we use nuclear medicine to assess whether the cancer has spread to their skeleton and there's really not other adequate way for us to do that," he said.