TORONTO -- For all the roster wrangling and chatter over who got left behind, Team Canada hopes its 25-man roster announced Tuesday will be enough to win a gold medal in Sochi.

Canada's management staff woke up after nine hours of meetings happy with the group selected, but the Olympic tournament doesn't happen in a vacuum. That's why when executive director Steve Yzerman was asked which country he was most worried about, he replied: "Every one."

"International hockey is getting more difficult for Canadians every day," Yzerman said Tuesday. "These countries are all improving. It's becoming very tough. To pick one country and say, 'That's our biggest rival, our biggest fear.' I'm nervous about them all. You can't overlook anyone anymore."

When it comes to medal contention, it would be easy to overlook Latvia, Norway, Austria, Slovenia and perhaps even Switzerland. But beyond that it's anyone's game among Canada, the United States, Sweden, Russia, Finland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

From a pure talent standpoint, Canada has the edge, especially at forward because of the availability of so many high-end centres, from Sidney Crosby and Jonathan Toews to John Tavares, Ryan Getzlaf and Patrice Bergeron.

"I think the strength of the team right from the get-go was down the middle of the ice," said Doug Armstrong, St. Louis Blues general manager and part of Team Canada's staff. "Our five centre-ice men have experience and are all proven winners."

Sweden has strong centres with Henrik Sedin, Nicklas Backstrom and Alexander Steen, but no country can touch Canada's depth there. The United States has big wingers, but among Joe Pavelski, Ryan Kesler, David Backes, Paul Stastny and Derek Stepan there's no clear-cut No. 1 down the middle, while Canada could have three top-line centres.

Armstrong likes Canada's size on the wings and those players' ability to skate. The U.S. has an advantage there with more natural wingers like Zach Parise, Dustin Brown and smooth skaters like Max Pacioretty and Blake Wheeler.

With wingers like Loui Eriksson, Daniel Sedin and Daniel Alfredsson -- among others -- Sweden may be best built for the international-sized ice where physical play isn't nearly as important as playmaking.

Russia's high-end talent up front is impossibly to deny: centres Pavel Datsyuk and Evgeni Malkin and wingers Alex Ovechkin and Ilya Kovalchuk are a formidable force and they should play major minutes.

"I think the biggest (strength) is just the mentality because we're Russians and we're going to play," Ovechkin said on a conference call Tuesday.

The Czech Republic's deep group of forwards shouldn't be overlooked, either, especially if Jaromir Jagr shines in the Olympic spotlight. There's plenty of unheralded offensive talent there in Milan Michalek, Tomas Plekanec, Jakub Voracek and others.

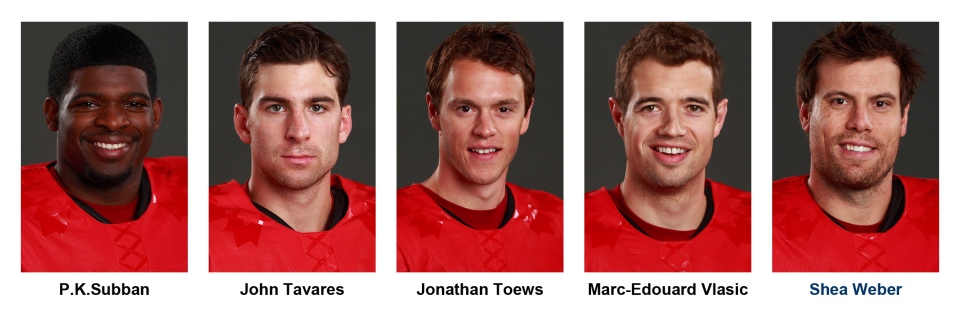

On defence, Armstrong praised Canada's experience. Duncan Keith, Shea Weber and Drew Doughty are back from 2010, with players like Jay Bouwmeester, Alex Pietrangelo and P.K. Subban filling a rather large hole left from the defencemen who are no longer around.

"Those two Hall of Famers on D in (Scott) Niedermayer and (Chris) Pronger, they're not here," Yzerman said. "We like the defensive core."

Canada coach Mike Babcock called it an "unbelievable back end that can transport the puck and get it going in a hurry."

It's good, but it's hard to top Sweden, which boasts Oliver Ekman-Larsson, Erik Karlsson, Alexander Edler and Niklas Kronwall. Puck-movers and skaters will be at a premium on the international ice, as Sweden showed by winning gold in Turin in 2006.

But one of the biggest reasons Sweden won eight years ago was in goal because of the play of goaltender Henrik Lundqvist. The edge in goal in this tournament there goes to Finland because of its likely starter and handful of options.

Tuukka Rask came within two victories of winning a Stanley Cup with the Boston Bruins last year, and his .942 even-strength save percentage is near the top of the league and best among Olympic goaltenders. If Rask falters in Sochi, Finland can turn to 2010 Cup-winner and 2013 Vezina Trophy finalist Antti Niemi, and its third option is Kari Lehtonen.

Goaltending almost won the U.S. gold in Vancouver because of Ryan Miller, so his return along with 2012 Conn Smythe Trophy-winner Jonathan Quick makes the Americans again worth talking about in net.

"Millsy and Quicky, they're tremendous players in their own (right)," third goaltender Jimmy Howard said. "Ryan's got a Vezina, Quicky, he's got a Conn Smythe and a Stanley Cup. Not to mention Ryan was the MVP in 2010."

If Jaroslav Halak puts together two magnificent weeks, there's no reason why Slovakia can't challenge for a medal. Russia's Semyon Varlamov and reigning Vezina winner Sergei Bobrovsky give them a legitimate gold-medal chance, too, beyond just being motivated to win on home soil.

Of course plenty can change on these rosters before the tournament begins Feb. 12. By the time Canada opens against Norway on Feb. 13, it may or may not have Steven Stamkos or the rest of this 25-man roster intact.

"We're going to be a work in progress once we get there," Babcock said. "The guys understand that and know that, and they have high hockey IQ. They process information great and they'll be detail-oriented."

That's where it helps having 11 players back from Vancouver. And those who are new, like Tavares, Matt Duchene and Jamie Benn up front, Bouwmeester on the blue-line and Carey Price in goal provide answers to different questions about Sochi.

"We wanted that blend of experience, of some youth, some speed, some high IQ," said Ken Holland, a member of Team Canada's braintrust and GM of the Detroit Red Wings. "You want to have as many different dimensions as you possibly can."