Angelo Dundee. Bundini Brown. Dr. Ferdie Pacheco. All well-known Muhammad Ali cornermen.

But there may not have been a triumphant second act to Ali's career without Leroy Johnson in his corner.

The former Georgia state senator was the driving force in Ali's return to the ring on Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta. Ali had to surrender his passport during his battle through the legal system after refusing induction to the U.S. Army in 1967, so he couldn't fight outside the country. He couldn't fight in the U.S. either, as attempts to get a boxing license were met with resistance for 3 1/2 years.

Enter Johnson, an African-American who saw an opportunity in the Peach State.

"My passion was to beat the system because the system had done Ali wrong," Johnson, 87, told The Associated Press in a phone interview.

Johnson is unable attend Friday's memorial service in Louisville, Kentucky, for Ali, who died on June 4 at 74. But he'll be watching and reflecting on his relationship with the three-time champion.

"He was such a tremendous personality," said Johnson, who Ali called "Big Man." "What impressed me that he had so much faith in himself."

The way he cleared the way for the Quarry fight, Johnson showed Ali that he probably should have had a little more faith in him.

Johnson worked with entrepreneur Harry Pett and got Ali licensed in Atlanta, a significant move since Georgia didn't have a boxing commission. Johnson said then-Gov. Lester Maddox initially supported the fight before publicly opposing it following protests by the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizens Council. The senator said shots were also fired into his home.

"I just kept thinking of all the cities that wouldn't grant him a license," said Johnson, who became Georgia's first black state legislator since the end of Reconstruction with his 1962 election.

Johnson first had to arrange an exhibition for Ali at Morehouse College - he's an alum - before the comeback fight at Municipal Auditorium against Quarry, a leading heavyweight contender.

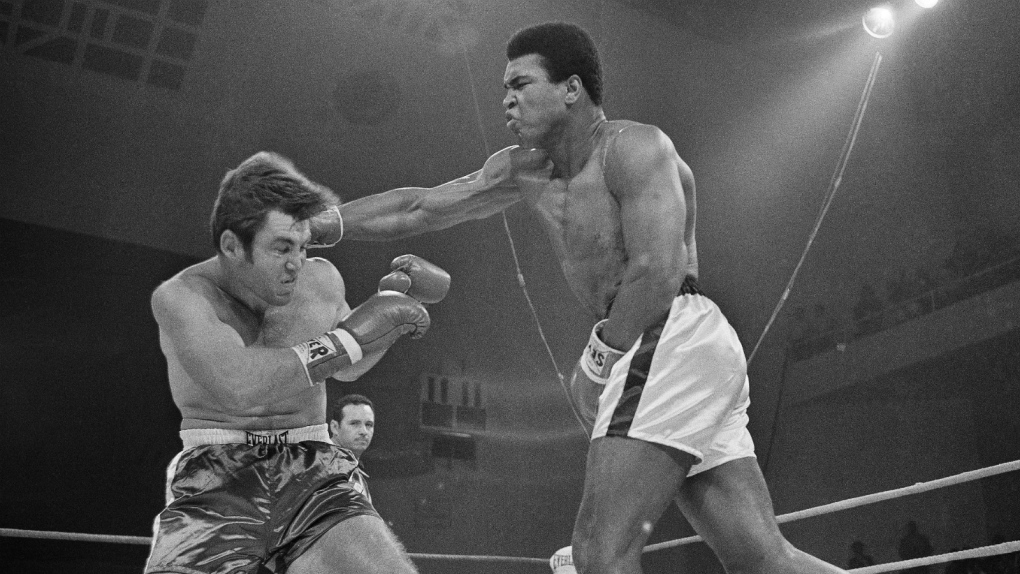

Ali dispatched Quarry before a delighted sellout crowd of 5,100 that included civil rights leaders Andrew Young and Coretta Scott King, and celebrities such as Gladys Knight, Hank Aaron and Bill Cosby.

There was plenty of glitz, glamour and gaudiness around the fight- a precursor of Ali's epic fight with Joe Frazier just five months later at New York's Madison Square Garden.

"It was the first time (with) all of the big-time gamblers and racketeers," Young jokingly recalled in a phone interview with the AP. "There were more long cars and full-length mink coats and fur hats on men and women than I had ever seen in my life."

Young considers Ali's return to the ring in Atlanta fitting because of the city's place in the civil rights movement.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson says Johnson was the right man championing Ali's cause. Jackson noted that Johnson had previously stood up for newly elected Julian Bond as legislators tried to block him from taking his seat in the House because he opposed the Vietnam War, like Ali.

"Leroy was the bridge for Ali from exile into the ring," Jackson said.

For Johnson, it was - and still is - all about Ali. Johnson recalled an urgency to get the fighter working again and generating positive publicity with everyone unsure how the U.S. Supreme Court would decide Ali's fate and when.

After the fight, an elated Ali gave Johnson the gloves he wore. Johnson said Ali told him, "I didn't think you could do it, but you did."

Johnson still has the gloves in a case at his home in Atlanta.

"Those gloves are very special," he said, "because he was a special man."