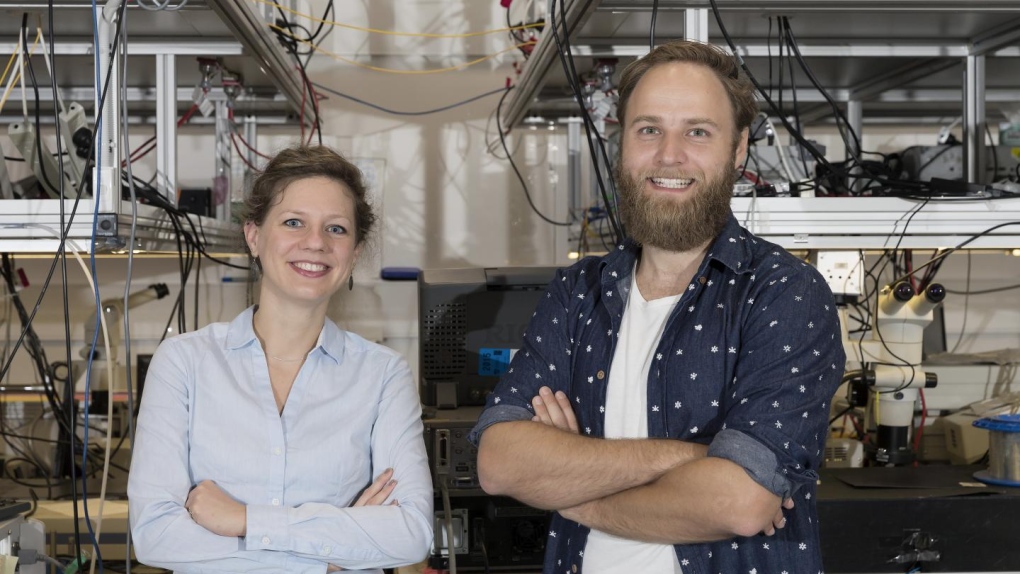

Australian researchers have created a microchip that converts light into sound waves and then back again for the first time ever.

The achievement, published in Nature Communications journal Monday, is touted as a huge step towards creating better, faster and more efficient computers.

Traditional computers and digital networks of today rely on electrons to transfer data but as the processing power of computers continues to increase, there are certain things that start to create problems.

For example, transfer data rates are limited by the speed of electrons, while resistance in circuits makes our computerized devices hot.

But a new microchip, developed by researchers at the University of Sydney, could herald a major change in the way computers work.

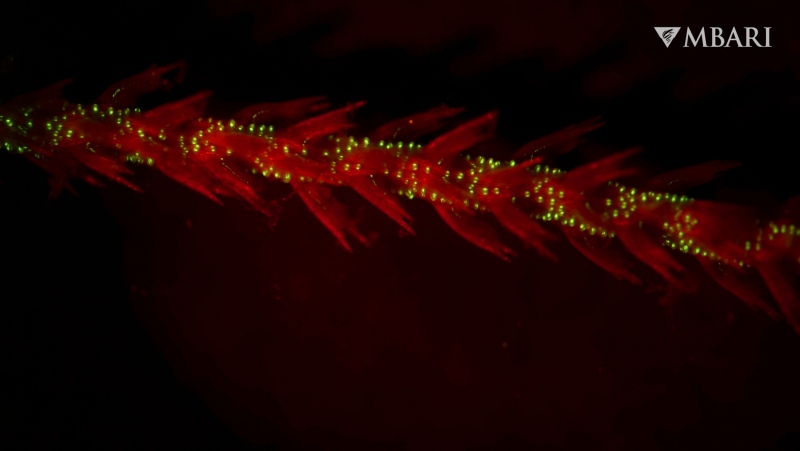

This chip, fabricated at the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Ultrahigh bandwidth Devices for Optical Systems (CUDOS), takes light-based data, in the form of photons, and stores them as sounds waves.

Light-based computers are considered ideal, because photons don’t produce heat, can travel quicker than electrons, and aren’t affected by electromagnetic radiation.

There’s just one tiny problem: photon-based data is too fast for current-tech computers to process, rendering them effectively useless.

Until now.

“The information in our chip in acoustic form travels at a velocity five orders of magnitude slower than in the optical domain,” Birgit Stiller, research fellow at the University of Sydney and supervisor of the project, said in a statement Monday. “It is like the difference between thunder and lightning.”

Similar to how there is a gap between the flash of lightning and the boom of thunder, the delay between the light and sound in the chip “allows for the data to be briefly stored and managed inside the chip for processing, retrieval and further transmission as light waves,” according to the statement.

In other words, the researchers managed to slow down light so the chip could do something with the data.

"Our system is not limited to a narrow bandwidth. So unlike previous systems this allows us to store and retrieve information at multiple wavelengths simultaneously, vastly increasing the efficiency of the device," said Stiller.

Several companies including IBM and Intel are working on light-based computer chips, but it may be sometime before the chips are in everyday computers.

Nonetheless Benjamin Eggleton, CUDOS director and co-author, said: "This is an important step forward in the field of optical information processing as this concept fulfils all requirements for current and future generation optical communication systems."