A breathtaking new photo series offers an inside look at the muddy, frigid, high-pressure, high-reward hunt for illegal mammoth tusks in northern Russia.

The photos, which were captured by embedded photographer Amos Chapple for Radio Free Europe, document the day-to-day lives of "tuskers" in northern Siberia, who operate outside the law in their search for precious prehistoric ivory.

A tusker melts permafrost to reveal a mammoth tusk in Russia's Siberia region. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

These "ethical" ivory poachers set out into the wilderness each summer to hunt for mammoth tusks that have been preserved in the region's thick permafrost.

A tusker camp is shown along a river in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

Many expeditions operate at a loss, but those that do get lucky often bring home tusks worth approximately US$30,000 each in cash, which they sell to "agents" who allegedly take the tusks back to ivory-obsessed China. The tusks are later carved into ornate designs and sold for more than $1 million each.

Carved tusks are shown in this display owned by a Chinese collector. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

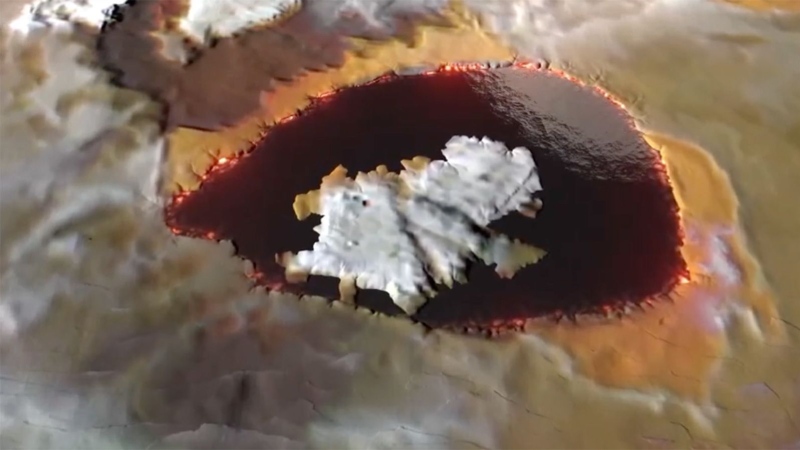

The industry in Siberia started a few years ago, when poachers would search for tusks by plunging sharp sticks into the permafrost. Efforts have ramped up since then, with teams of tuskers now heading out on summer-long expeditions into Russia's remote Yakutia region, where they use fire hoses to blast deep tunnels and caverns through the permafrost in search of ivory.

A tusker searches for ivory in this cavern under the permafrost in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

The fire hose method – known as hydraulic mining – is illegal, but Chapple says that doesn't deter the locals from doing it. He explained that the silt from the hydraulic pumps seeps into the nearby river and makes it uninhabitable for marine life. However, the tuskers have learned to dodge environmentalists and police, so as to avoid the relatively minor fine of $45 for first and second offences. They are only called to face a judge after the third offence.

The region where they mine is thought to have been a swamp or bog some 10,000 years ago, with all of the intact remains preserved by the permafrost blanketing the area.

Chapple says it's a hard life for these tuskers, the majority of whom fail to turn a profit while chasing stories of "instant, spectacular wealth" under the permafrost.

"They're basically working-class Siberian guys," Chapple told CTV News Channel on Monday. "in the summertime there's either fishing or tusk hunting, and tusk hunting is seen more and more as the thing to do."

The men sleep in tents, eat cans of beef and noodles, and occasionally resort to cooking dogs when food gets truly scarce. They also fend off large clouds of mosquitoes that will quickly cover exposed flesh, with some even going so far as to wear beekeeper-like outfits for protection.

"They're around you constantly, like a great big cloud that you can't escape," Chapple said.

Mosquitoes cover a tusker's feet in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

He described following his tusker team as an "intense" experience, especially when the 60 or so members of the team broke out the vodka. "Twice, guys turned on me," he said. "Anytime there was vodka in the camp, which was twice when I was there, things get pretty ugly."

Temperatures are above freezing during the day, but they remain frigid in the underground tunnels where tuskers go to search for their "white gold."

However, the tuskers hang on through these harsh conditions in hopes of hitting a big score, such as the $100,000 cash one team reported earning on an eight-day expedition. Another tusker said he earned $34,000 for a 65-kilogram tusk. That's a big payday for these men, who come from towns where the average pay is $500 a week.

Mammoth tusks are the biggest prize for these tuskers, but they can also cash in by recovering the horns of extinct woolly rhinoceroses, which are also found trapped in the ice.

A tusker emerges from a permafrost tunnel with a woolly rhino skull in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

Buyers pay approximately $14,000 for a good horn, which will be sent to Vietnam and ground up to make "medicine" thought to cure cancer.

Chapple, who held a 2.4-kilogram horn in his hand, said it "squelches like soggy driftwood and smells of unwashed dog."

A man examines a woolly rhino horn (Amos Chapple / RFE)

Chapple describes the permafrost itself as a "great, dirty iceberg," topped by a layer of dirt and moss. The mammoth tusks would have rotted away millennia ago in the dirt, but the permafrost has kept them perfectly preserved.

The bones of these prehistoric mammals are typically discarded as worthless, and the hillsides are left behind in their ravaged state. In many cases, silt runoff from the melted permafrost will actually affect water levels in the nearby rivers, permanently altering the landscape.

A pockmarked hillside is shown after a tusker excavation in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)

Although the practice is illegal, the poachers are good at dodging law enforcement, with lookouts regularly posted to watch for police boats coming down the river. Those who are caught typically face a $45 fine, with no further penalty until the third offence.

One tusker acknowledged the danger and damage caused by the industry, but admitted he simply doesn't see another option to provide for his family.

"No work, no kids," he told Chapple. "I know it's bad, but what can I do?"

A man emerges from a tent at a tusker camp in Siberia, Russia. (Amos Chapple / RFE)