DOHA, Qatar -- The first signs of tensions emerged at the UN climate talks on Tuesday as delegates from island and African nations chided rich countries for refusing to offer up new emissions cuts over the next eight years which could help stem global warming

The debate mostly swirled around the Kyoto Protocol -- a legally-binding emissions cap that expires this year and remains the most significant international achievement in the fight against global warming. Countries are hoping to negotiate an extension to the pact that runs until at least 2020 but several nations like Japan and Canada have said they won't be party to a new one.

Marlene Moses, chairwoman of a coalition of island countries, said she was "gravely disappointed" with rich nations, saying they have failed to act or offer up any new emissions cuts for the near term. The United States, for example, which is not a signatory of Kyoto, has said it would not increase earlier commitments to cut emissions by 17 per cent below 2005 levels by 2020.

"In our view, these actions are an abdication of responsibility to the most vulnerable among us," Moses said.

In its current form, a pact that once incorporated all industrialized countries except the United States would now only include the European Union, Australia and several smaller countries which together account for less than 15 percent of global emissions he Japanese delegation defended its decision not to sign onto a Kyoto extension, insisting it would be better to focus on coming to an agreement by 2015 that would require all countries to do their part to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F), compared to preindustrial times.

"As we have been explaining, only developed countries are legally bound by the Kyoto Protocol and their emissions are only 26 per cent," said Masahiko Horie, speaking for the Japanese delegation.

"If we continue the same, only one quarter of the world is legally bound and three quarters of countries are not bound at all," he said. "Japan will not be participating in a second commitment period because, what is important, is for the world is to formulate a new framework which is fair and effective and which all parties will join."

The position of Japan and other developed countries has the potential to reignite the battles between rich and poor nations that have doomed past efforts to reach a deal. So far that hasn't happened, but countries like Brazil are warning that it will be difficult for poor nations to do their part if they continue watching industrialized nations shy away from legally-binding pacts like Kyoto.

"This is a very serious thing," said Andre Correa do Lago, who heads the Brazil delegation and is the director general for Environment and Special Affairs in the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

"If rich countries which have the financial means, have technology, have a stable population, already have a large middle class, if these countries think they cannot reduce and work to fight climate change, how can they ever think that developing countries can do it," do Lago said. "That is why the Kyoto Protocol has to be kept alive. It's the bar. If we take it out, we have what people call the Wild West. Everybody will do what they want to do. With everyone doing what they want to do, you are not going get the reductions necessary."

Many scientists say extreme weather events, such as Hurricane Sandy's onslaught on the U.S. east coast, will become more frequent as the Earth warms, although it is impossible to attribute any individual event to climate change. The rash of violent weather in the U.S., including widespread droughts and a record number of wildfires last summer, has again put climate change on the radar.

"It's probably not a coincidence," Jean-Pascal van Ypersele, vice chairman of the UN climate panel, told The Associated Press. "Climate is defined by trends and not by single events so it's never possible to attribute a single event to a changing climate. But what is clear over time is that the climate context is evolving and in that climate context many extreme events become either more intense or more frequent. And the kind of things that we have seen in the U.S. are likely to happen more in the future, together with heat waves and that kind of thing."

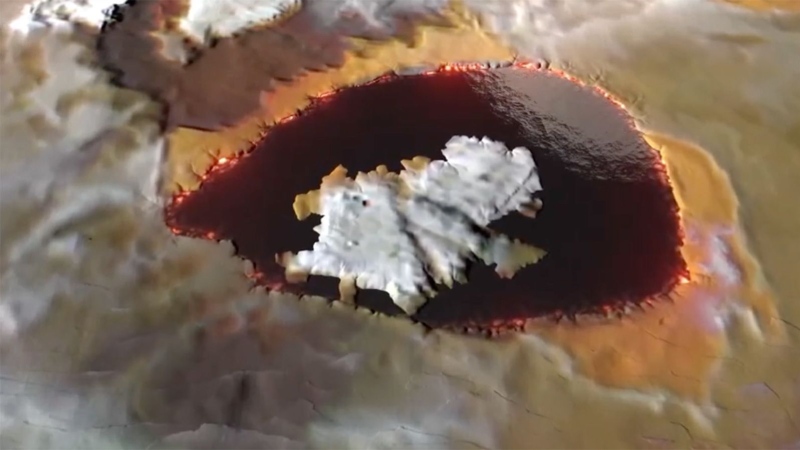

Meanwhile, a United Nations report warned that thawing permafrost covering almost a quarter of the northern hemisphere could "significantly amplify global warming" at a time when the world is already struggling to reign in rising greenhouse gases, a UN report said on Tuesday.

The UN said the potential hazards of carbon dioxide and methane emissions from warming permafrost has until now not been factored into climate models. It is calling for a special UN climate panel to assess the warming and for the creation of "national monitoring networks and adaptation plans" to help better understand the threat.

In the past, land with permafrost experienced thawing on the surface during summertime, but now scientists are witnessing thaws that reach up to 10 feet deep due to warmer temperatures. The softened earth releases gases from decaying plants that have been stuck below frozen ground for millennia.

"Permafrost is one of the keys to the planet's future because it contains large stores of frozen organic matter that, if thawed and released into the atmosphere, would amplify current global warming and propel us to a warmer world," said UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner in a statement.

Kevin Schaefer, of the University of Colorado National Snow and Ice Data Center, said 1,700 gigatons of permafrost exist. The lead author on the UN report, he warns that that melting could permanently amplify what is already a worrisome threat.

"The release of carbon dioxide and methane from warming permafrost is irreversible: once the organic matter thaws and decays away, there is no way to put it back into the permafrost," Schaefer said.