Step aside, triceratops. There’s a new contender for king of the three-horned dinosaurs, and he already has a crown.

Paleontologists at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta have unearthed the fossilized skull of a never-before-seen cousin to the triceratops, with a “bizarre” set of horns and a crown-like frill unique to dinosaurs of its kind.

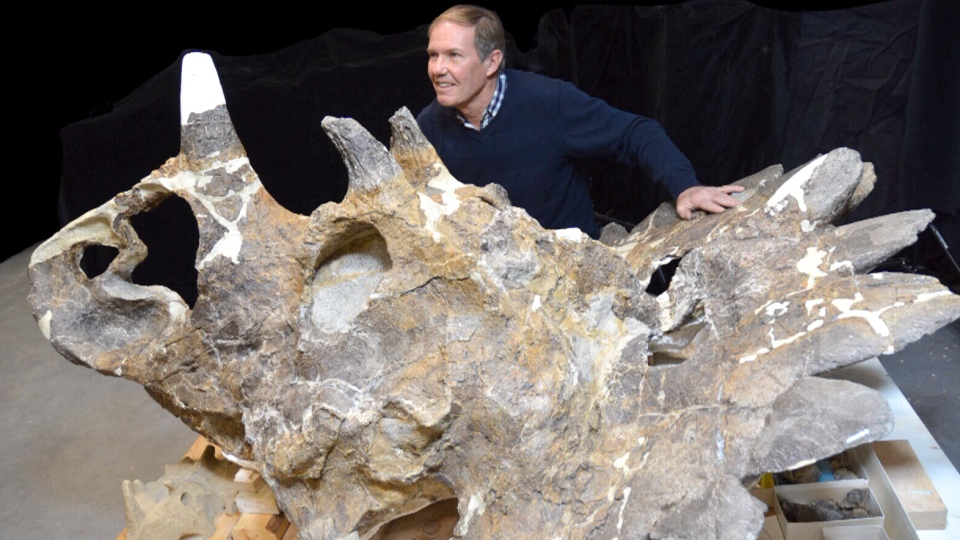

The new dino, dubbed regaliceratops peterhewsi, lived approximately 70 million years ago and grew to roughly the size of a large SUV. The 1.5-tonne beast had a large nose horn, small secondary horns over its eyes and a jagged-edged, shield-like frill at the back of its skull. The frill is the largest ever recorded among three-horned dinosaurs, with oversized, plate-like protrusions jutting out from the top.

Brown calls the regaliceratops an “evolutionary convergence” between two branches of the horned dinosaur family. Regaliceratops is closely related to the well-known triceratops, but its horns and frill are throwbacks to a breed that died out millions of years before regaliceratops ever lived.

Brown and his colleagues spent 10 years unearthing a mostly intact regaliceratops skull, which will go on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum on Thursday.

“It’s a very impressive skull, so you can see exactly what this animal looked like,” Brown told CTVNews.ca by phone. He says the skull was almost entirely intact, with only the lower jaw and beak missing. That allowed paleontologists to conclusively determine that it was unlike anything they’d ever seen before. “You can see parts of the anatomy that just don’t match up with known species,” he said.

A riverside find

Calgary geologist Peter Hews first laid eyes on the regaliceratops fossil back in 2005, when he spotted a piece of bone in a cliff overlooking Oldman River, in southwestern Alberta. He called the Royal Tyrrell Museum in to excavate it, and the museum researchers thanked him by naming the dinosaur after him.

And while regaliceratops peterhewsi is the full, official name, the dinosaur is commonly known around the Royal Tyrrell Museum by a simpler moniker: Hellboy.

Brown says the nickname sprang from the “hellish” 10-year excavation process that paleontologists went through to get the skull ready for display. Diggers had to extricate the skull from a steep riverside cliff that overlooks a bull trout spawning ground. The bull trout are a protected species in the province of Alberta, so Brown and his team had to dig out the fossil without dropping any dirt or sediment into the river below.

“That mean that the process had to be longer and more difficult,” he said.

The whole skull was encased in extremely hard rock, and it took paleontologists a year-and-a-half to fully uncover the fossilized bones.

The regaliceratops skull was found in the Rocky Mountain foothills of southwestern Alberta, a region where paleontologists don’t typically expect to find fossils, Brown said. Dinosaur bones are far more common in the badlands of the southeast.

Brown says his team will now widen their research area to include the southwest, in hopes of finding more undiscovered species. “We’ll definitely go back and look for more,” he said.

Age of dino-discovery

The Royal Tyrrell Museum uncovers a new dinosaur species approximately once every five years, but Brown says the regaliceratops find is special.

“This is probably one of the most exciting ones that we’ve been involved with,” he said.

Brown says there might have been millions of regaliceratops on Earth at one point, but it’s extremely rare for any living creature to become fossilized. He says less than one per cent of the dinosaurs were preserved as fossils, and many of those fossils do not survive the compression and erosion that occurs over 65 million years.

Still, paleontologists are in the middle of a golden age of discovery, with more new species turning up now than ever before, Brown said.

“We’re finding dinosaurs incredibly rapidly nowadays, on a global scale,” he said.

Brown and co-author Donald M. Henderson published their regaliceratops findings in the June 4 edition of the journal Current Biology.

This is where the new dino was discovered, 10 yrs ago by Calgary geologist & dino lover Peter Hews. "I was lucky." pic.twitter.com/RhuA4oBv4E

— JanetDirks (@janetdirks) June 4, 2015

Here you can see the bones. The new dinosaur is getting it's debut this morning at Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller pic.twitter.com/SszURsWtRY

— JanetDirks (@janetdirks) June 4, 2015

They called the dino "Hellboy" because so difficult to haul it out of the hard rock. 10 yrs from discovery to now. pic.twitter.com/ljNLyIkL92

— JanetDirks (@janetdirks) June 4, 2015

They have the skull complete with its frill (this is a horned dinosaur). Great excitment at Royal Tyrrell Museum. pic.twitter.com/KlJJ4febiv

— JanetDirks (@janetdirks) June 4, 2015