New technology to clean water filtration systems developed at the University of British Columbia (UBC) could drastically lower the cost of delivering clean drinking water to Canada's First Nations communities and remote regions around the world.

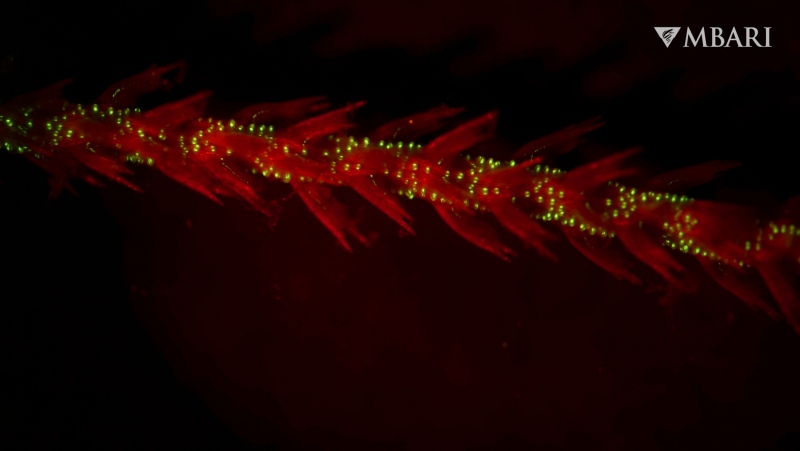

It's capable of removing over 99.99 per cent of dirt, organic particles, bacteria, and virus-based contaminants from otherwise undrinkable water using a fibrous spaghetti-like membrane.

That technology has been around for decades. But unlike most municipal systems, this one is about as easy to maintain as a fish tank, according to its designers.

UBC civil engineering professor Pierre Bérubé told CTVNews.ca that many small and remote communities are able to raise the money to build a water treatment plant, but the high cost of employing skilled workers to keep the system clean often leads to neglect and ultimately undrinkable water.

"What our technology does is it removes the need for all those chemicals and complex mechanical systems," Bérubé said Tuesday. "We've gone from a system that essentially requires 24-hour-a-day attention to something that requires half-an-hour-a-day of attention."

He estimates about half of the infrastructure at most water treatment plants is dedicated solely to removing contaminants from clogged membranes with chemicals, motors, and pumps. This new simplified design relies instead on gravity, and hungry bacteria, to get the job done.

The dirty water falls through tanks filled with the fibre membranes that latch on to particles such as dirt, bacteria and viruses while the liquid filters through.

"You just need to cause liquid flow and turbulence around the membrane to scour it clean. The way we do that with gravity is basically analogous to taking a bottle of water and flipping it over. As the water rushes out, air rushes in," said Bérubé. "At the same time, in our system we have microorganisms that grow and eat away at the contaminants."

The operational cost savings could be a godsend in communities where budgets for municipal staff are slim. Bérubé said the critical job of managing rural water supplies all too often fall on the shoulders of someone with several other jobs on their plate.

"Often it is a part-time person that is responsible for the water treatment system that is also responsible for maintaining fire hydrants, cleaning the roads, and a whole bunch of other civil infrastructure requirements," he said. "Our system under those circumstances becomes very feasible. All you need to do is go in every day and check the system to make sure it is still functioning, and do a bit of routine cleaning."

Bérubé's efficient design is well timed given the number of First Nations and remote communities in desperate need of functioning water infrastructure. One in four living on a First Nations reserve may not have access to clean water, according to an estimate by The Council of Canadians released last week.

"In pretty much all provinces there is a number of communities that are currently on boil water advisories, literally in the number of thousands of small systems," said Bérubé. "In B.C. at any one point in time, I think there are over 300, up to 500 boil water advisories."

UBC plans to begin testing the new system in West Vancouver next week. The researchers plant to eventually broaden the pilot project to partnering small communities in the province.

Watch a video about the technology on YouTube: