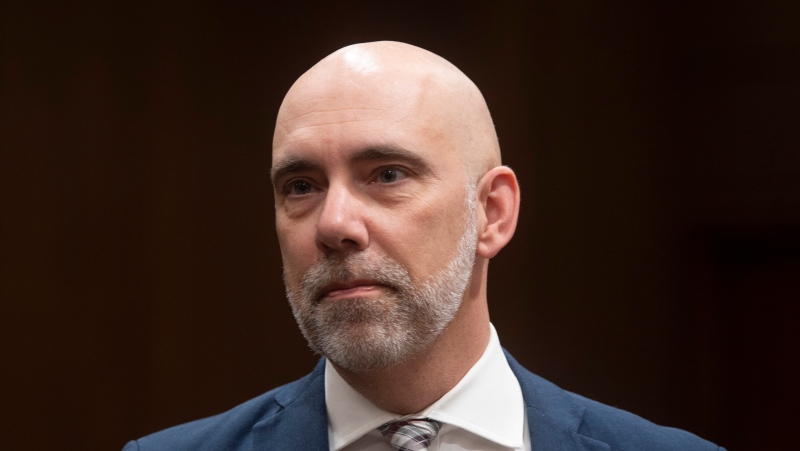

Now that the Progressive Conservative party has been sent back to the opposition benches for a fourth straight election, they will be looking back at what went wrong with Tim Hudak’s campaign strategy.

Following the loss Thursday night, Hudak announced he would resign as party leader.

“I am proud of what of what our team has accomplished and I am optimistic about our party’s future, but I will not be leading the Ontario PC party into the next election campaign,” he said to a crowd of supporters in his home riding of Niagara-West Glanbrook.

Hudak said he will remain party leader until the caucus chooses his replacement.

Analysts attributed Hudak’s loss to his inability to connect with Ontario’s voters. His “Million Jobs” plan just didn’t resonate with people, and his personality could not compete with Liberal Kathleen Wynne’s “likability” factor.

PC strategist Ralph Lean says that even more than the job creation plan, Hudak’s downfall was a promise to cut as many as 100,000 public-sector jobs.

“I think using the 100,000 job number hurt,” he said to CTV News. “That stuck. We thought it would get our core out. It didn’t.”

Hudak had campaigned on a love of numbers. During the Ontario debates, he recounted tales of family road trips. His father would ask him math questions or get him to recite his multiplication tables. He received his undergraduate degree in economics from the University of Western Ontario and a Master’s degree from the University of Washington in Seattle.

He felt so strongly opposed to the government’s “discovery math,” a new form of teaching that involves open-ended methods of problem solving instead of using traditional formulas, that he suggested returning back to the original school curriculum.

“When students graduated, employers soon discovered that people couldn’t do basic math. So they didn’t get the job,” Hudak said during the Ontario election debates. During the debates, Hudak also promised to bring in specialty math teachers and create a new provincial science test that will help prepare young kids for the realities of the workforce.

Still, economists said the Million Jobs math didn’t work out, either. He also failed to explain how his Million Jobs plan would work in terms people could understand.

“I think (Hudak’s) biggest problem is that he spent the last year talking about negative scandals instead of talking about and selling his million jobs plan,” political strategist Jim Warren told CTV News.

Here is a recap of the PC number-based platform:

- Creating a million jobs: Hudak’s Million Jobs plan was the centre of his campaign strategy. He claimed that by reducing government spending, shrinking the cabinet, and cutting jobs as current employees retire, he will create an abundant number of trade and entry-level positions for residents of Ontario. He was so confident in this plan that he said he would resign if he did not follow through with it.

- Balancing the budget: In addition to creating a million jobs, Hudak has also pledged to balance the Ontario budget by 2016, ridding the province of its projected $11.3-billion deficit. In order to do so, he will invoke a minimum two-year wage freeze on government employees and cut 100,000 non-essential public sector jobs. He estimates this could save the government at least $2 billion a year.

- Cutting taxes: This campaign pledge may be years in the making. Hudak is promising a 10 per cent personal income tax cut once the budget is balanced, presumably in 2016. Back in May, he also promised to reduce corporate taxes by 30 per cent.

Speaking with CTV’s Paul Bliss two days ago, Hudak realized not all voters would connect easily with his ideas or personality.

“This is life. I think when people see me … they will see in Hudak a guy who calls it as it is,” he said to Bliss. “That had the courage to look in the camera during the debate and say I’m not trying to be a great actor and try to fool you. I’m going to be the guy who is going to get things done.”

Even Thursday night, as he walked quickly off the stage after announcing his resignation, he was firm in that belief.

“We ran a damn good campaign. We just didn’t get the results we hoped for.”