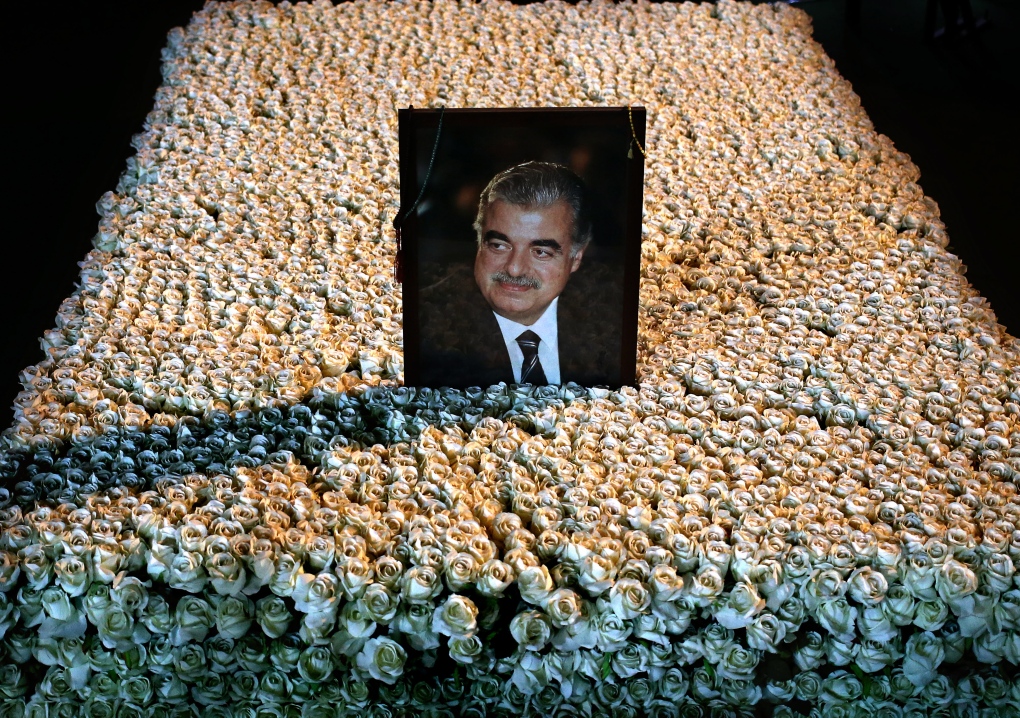

BEIRUT -- The truck bomb assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri sent a sectarian tremor across the Middle East and set off years of upheaval in Lebanon, the consequences of which are still felt across the turbulent region.

Nine years later, the international trial of four Hezbollah suspects is finally set to begin.

With Sunni-Shiite tensions at an all-time high, exacerbated by the raging civil war in Syria, some fear a fresh outbreak of deadly violence because of a trial it had been hoped would help put an end to Lebanon's long tradition of unsolved political assassinations.

Faith that justice would eventually prevail has faded over time. Many Lebanese believe the tribunal is politicized, and many involved in the investigation have died. None of the suspects have been arrested, and Hezbollah has vowed never to hand them over.

The suicide assassination with a ton of explosives that killed Hariri and 22 others on Feb. 14, 2005 was one of the most dramatic assassinations in the Middle East's modern history, helping fuel sectarian divisions between Sunni and Shiite Muslims. Violence between members of the two sects has claimed the lives of thousands over the past years mostly in Iraq, Syria, Pakistan and Lebanon.

Hariri, who also held Saudi citizenship, was one of Lebanon's most influential Sunni leaders, with wide connections in the Arab world and international community. Hezbollah, a Shiite group, is backed by Shiite Iran.

In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, suspicion fell on Syria, since Hariri had been seeking to weaken its domination of Lebanon. Syria has denied any role in the murder, but the killing galvanized opposition to Damascus and led to huge street demonstrations dubbed the "Cedar Revolution" that helped put an end Syria's 29-year military presence in its smaller neighbour.

Lebanon has a history of political assassinations for which no one has ever held accountable. In the emotional days following his death, Hariri supporters called for an international investigation, and a UN-backed court was established in 2009.

"I think that for the first time since 1943, Lebanon is about now to discover the truth through an independent tribunal," said former Justice Minister Charles Rizk, referring to political killings since Lebanon's independence.

The trial opens Thursday on the outskirts of The Hague, Netherlands. Four members of the Syria and Iranian-backed Hezbollah group were indicted in 2011 with plotting the attack, but have not been arrested. A fifth was charged late last year in the case and is also still at large.

Hezbollah denies involvement in the murder and the group's leader, Sheik Hassan Nasrallah, has denounced the court as a conspiracy by his archenemies -- the U.S. and Israel.

"The start of the trial will be a historic day for Lebanon and international justice," the tribunal's spokesman Martin Youssef told reporters in Lebanon last week.

Since Hariri's killing, several people accused by anti-Syrian Lebanese politicians of having a role in the case have died.

Syria's Interior Minister, Brig. Gen. Ghazi Kenaan, died in his Damascus office in late 2005 about a month after speaking with investigators in Hariri's assassination. Syrian officials said he shot himself to death, but some in Lebanon believe he was killed. Kenaan ran Lebanon at the height of Syria's dominance of the country for two decades until 2003.

Syria's deputy Defence Minister Asef Shawkat was among other top generals killed in a Damascus bombing in July 2012. In 2005, an inadvertently released passage of a UN investigative report of the killing cited a witness saying that Shawkat, head of military intelligence at the time, was among those behind Hariri's assassination. Shawkat was the brother-in-law of Syrian President Bashar Assad.

In October, Maj. Gen. Jameh Jameh was killed while fighting rebels in eastern Syria. At the time of Hariri's assassination, Jameh was the second top Syrian intelligence official based in Lebanon and was Syria's intelligence chief in Beirut.

The four Hezbollah suspects include Mustafa Badreddine, believed to have been Hezbollah's deputy military commander, who also is the suspected bomb maker in the 1983 blast at the U.S. Marines barracks in Beirut that killed 241 Americans.

The other suspects are Salim Ayyash, also known as Abu Salim; Assad Sabra and Hassan Oneissi, who changed his name to Hassan Issa. The fifth to be indicted was Hassan Habib Merhi.

There are fears in Lebanon that the tribunal will open a new chapter of sectarian violence in a country where the Syrian civil war has spilled over with increasing frequency in the past few months. Sunni-Shiite tensions are soaring, and there has been a new wave of killings among Lebanon's Shiite and Sunni political factions.

Hezbollah has been fighting alongside Bashar Assad's forces in key areas near the border with Lebanon, angering the overwhelmingly Sunni rebels fighting to topple him. Sunni radicals have hit back with several car bombs against Hezbollah strongholds in Beirut.

Assassinations have continued. The last one targeted former Finance Minister Mohammed Chatah, who was killed in a car bomb on Dec. 27. Chatah was a close aide to Hariri.

"We and the international community wanted the tribunal to punish the criminals and to stop political assassinations," legislator Atef Majdalani, a member of the Future Movement bloc that is headed by Hariri's son, Saad, also a former prime minister, told The Associated Press.

There is little hope that the suspects would ever stand trial. International arrest warrants were issued for them nearly three years ago and they are all still at large. Hezbollah is the most powerful group in Lebanon and has a far more powerful arsenal than that of the national army.

In a defiant speech after the indictments were released in 2011, Hezbollah's leader said it will be impossible to arrest the suspects.

"No Lebanese government will be able to make any arrests whether in 30 days, 30 years or even 300 years," he said.