OTTAWA -- A significant shortage of RCMP officers is raising concerns about their safety and the safety of the communities in which they work, according to several Mounties speaking out from across Canada.

With more than 12 per cent of positions unfilled, RCMP members, speaking on the record and on background, tell CTVNews.ca that they're worried about the number of vacancies.

The lack of front-line officers is leading to stress, burnout and even to departures for other police forces, these members say.

"The HR crisis is the number one thing affecting our organization and there's no overnight fix to it," said Brian Sauvé, who serves as national executive co-chair for the National Police Federation, the organization that looks likeliest to become the union for the RCMP.

"There's no magic bullet to finding 4,000 or 5,000 more police officers that can alleviate our HR crisis in a timely fashion. It's going to be years," he said.

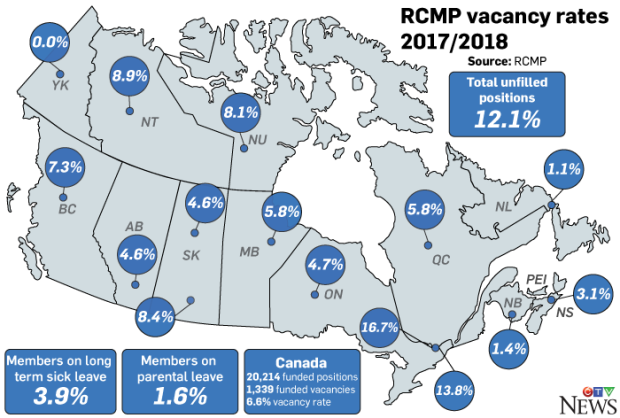

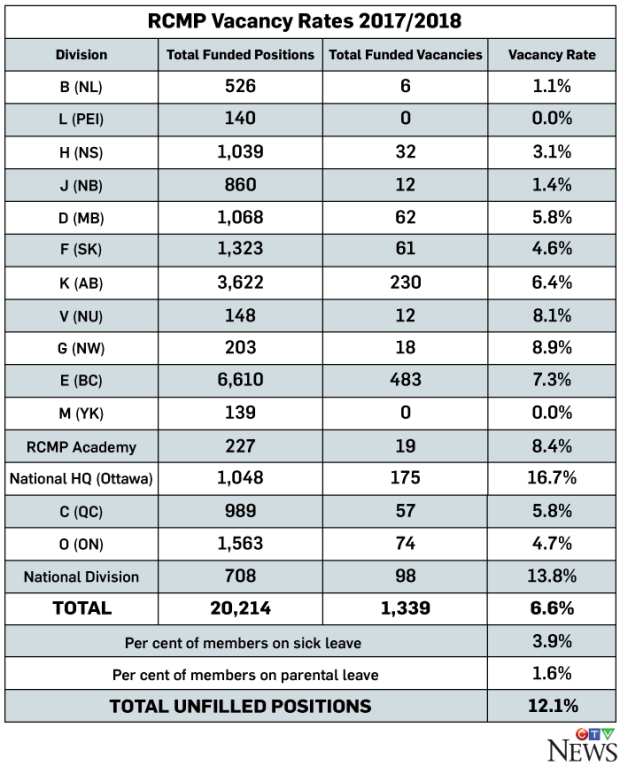

The RCMP says 6.6 per cent of the force's jobs nationally were vacant as of April 1, 2017, with another 3.9 per cent of members off on long-term sick leave, and another 1.6 per cent on maternity or paternity leave.

Graphics by Nick Kirmse / CTVNews.ca

That means an average of 12.1 per cent of RCMP member positions are sitting empty, leaving small detachments severely understaffed.

In a detachment of four people, for example, not back-filling someone who goes on family leave increases work for the remaining officers by 33 per cent.

"You're going to see, and you are seeing, burn-out from the membership.... That's consistent across the country," Sauvé said.

'Overworked' leading to 'disaster'

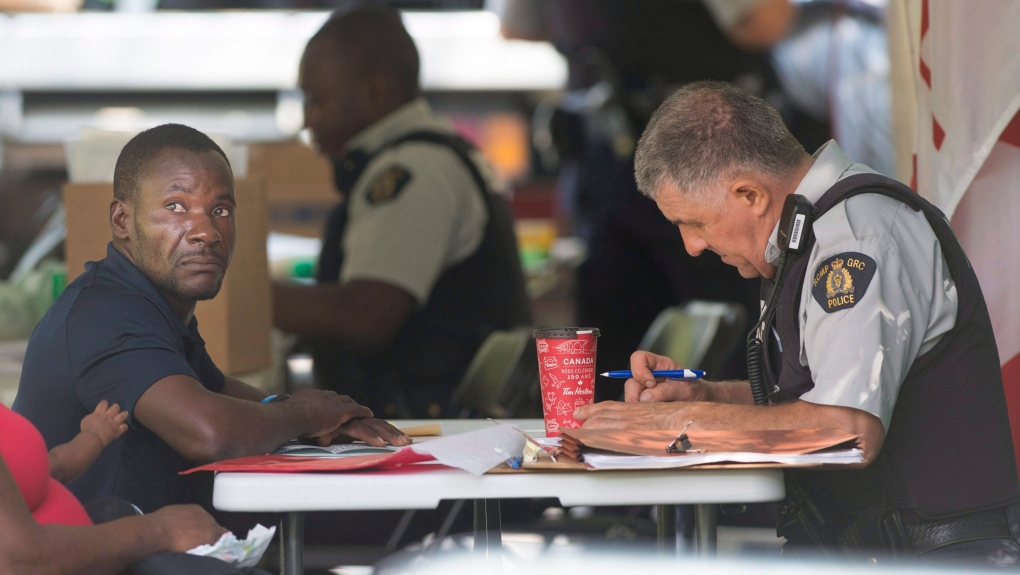

For small towns and remote communities in Canada, the RCMP provide contract police services that see them covering hundreds of square kilometres of sparsely populated areas, including dark, isolated rural roads where their radios may not work properly.

Now, many have to cover those areas without a full complement in their detachments.

Fear of burnout drove Cpl. James Smith to speak out publicly two weeks ago, following a meeting with his MP, Conservative Arnold Viersen.

"We are overworked, we're fatigued, we're exhausted, and I haven't seen any reason to be optimistic that it's getting better," Smith said of front-line RCMP members.

"In my 10 years of service... our workloads have just been going up and up and up."

Smith, who works at the Valleyview detachment about 300 kilometres north of Edmonton, calls the staffing shortages a "crisis" and a "mess."

"It's almost this perfect recipe for disaster," he said.

The vacancy rate -- which the RCMP considers to be unfilled but funded jobs, excluding sick leave and parental leave -- is as high as 16.7 per cent at national headquarters in Ottawa. The biggest provincial or territorial gap is in the Northwest Territories, at 8.9 per cent.

The Mounties initially provided the vacancy rate broken down by province and territory to CTVNews.ca, and didn't respond to follow-up requests for more than a month before adding the sick leave and maternity and paternity leave numbers.

Numerous sources also told CTVNews.ca that the RCMP will eliminate unfilled positions in order to lower the vacancy rates, not solving the resource problems but making the numbers look better. The RCMP didn't answer a question about how many vacant positions it eliminated in the last year.

The remaining members work additional hours and get called in on their days off because of the shortages.

"I'm seeing members with two and three years service showing signs of advanced fatigue and exhaustion," Smith said, adding his biggest concern is "members going to these high-risk calls for service when they're burned out, and they're exhausted, and they really shouldn't be working at that point."

'It has to be dealt with'

A spokesman for the RCMP refused CTV's interview request, saying the Mounties preferred to answer by email.

"The safety of the communities we serve and our members who serve them are our greatest concerns," Sgt. Harold Pfleiderer wrote to CTVNews.ca.

"Management employs a variety of strategies to help address vacancies and provide relief to employees, such as: authorizing overtime, calling up RCMP reservists and temporarily re-assigning staff from other detachments or divisions. We recognize the dedication and professionalism of our members who often go the extra mile to keep their communities safe and support each other."

One officer, who requested anonymity out of fear for his job, says he's on-call for three to five hours before his shift starts and two to three hours afterwards if he's on the night shift.

"Twelve hours seems to be the norm," said the Mountie, whose detachment is in a rural community.

"Most times you come home 2, 3 in the morning and if you're on call til 5, it never fails, you get called out at 4:59, 4:58, and it's an hour or two away."

(This experience is echoed by Smith).

The officer says he usually goes to calls by himself, with his nearest back-up anywhere from 65 to 80 kilometres away. He's stopped pulling over vehicles at night because he says it's too risky.

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, the minister responsible for the RCMP, declined an interview request. A spokesman responded to a list of emailed questions to say the government has already provided "integrity funding" for temporary support and is reviewing a report by KPMG into the RCMP's resources.

"It is important for the public to understand that as part of the planning, the level of funded positions takes into consideration that some positions are periodically unstaffed due to sick leave and maternity leave, and this does not represent a deficient service level to the public," Scott Bardsley wrote to CTVNews.ca.

"More broadly, the government is working to modernize the force to deal effectively with its long-term challenges and ensure a healthy workplace for all its officers -- which will help ensure that they are as effective as possible."

That includes increasing RCMP pay (the first increase in three years), reviewing reports on harassment within the RCMP and passing legislation to let Mounties form a union.

Concerns over the staffing shortages have led groups like the Alberta Urban Municipalities Association to start raising them during meetings in Ottawa.

"It's unfortunate that it has to become a [news] story," said Barry Morishita, a vice president with AUMA.

"It's kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy a little bit, right? We're going to talk about RCMP shortages and people are going to feel less safe... [but] it has to be dealt with."

Rural people 'paying the price'

The organization has heard anecdotal complaints about RCMP vacancy rates affecting response times, but nothing specific, Morishita said.

"We hear the complaining around the table fairly regularly that there are just not enough RCMP in some jurisdictions."

The Mountie who requested anonymity says his detachment used to have four RCMP members and a corporal, but after losing one member a few years ago, the position was eventually eliminated.

Now, people in the community show up at his home if they can't reach anyone by phone. It can take hours or even until the next day for the RCMP to respond to non-urgent calls, he said.

"It's ridiculous. It was never like that before. Before, the response time was 15 minutes and there was a member somewhere... The people who are paying the price for that are the rural people.

"Even the criminals know that 'by the time they call the police, I could be 30, 40 minutes out of here'."

He says that's led to people retaliating, risking being charged themselves for protecting themselves or their property.

Lose up to 800 members a year

It's not just member staffing that's plaguing the force. Mounties also say it takes months to get kit like new pants or utility belts (the RCMP says it has approved a plan to address the backorders). Radios don't always work in the more remote parts of the country where they patrol. And dispatching and statistics-keeping have also slowed due to staffing shortages.

Some of these problems are making it harder to retain trained members. Stories abound of Mounties leaving for the Edmonton and Calgary police forces, or the Ontario Provincial Police, all of whom pay better and provide better gear, without the same concerns there aren't enough officers for back-up.

The OPP says it can't break down how many officers it hired with RCMP experience, but so far in 2017 has picked up 30 officers with experience on other forces. The year before, it hired 38 experienced police officers.

An Ottawa police spokeswoman says it has hired three former RCMP officers since April, 2016, emphasizing that the officers weren't recruited but applied for the jobs.

Last February, former RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson told a Senate committee that the Mounties aim for a four to five per cent vacancy rate.

"It is not ideal, but a fair, balanced and thoughtful approach to how the vacancies are shared across the country," he told senators on the security and defence committee.

"Stress on our employees and overworked employees is a failure of management rather than the amount of resources. We have to prioritize our work, let our employees do what they can, make sure they're properly supervised and managed, and meanwhile argue effectively, thoughtfully and transparently for more resources."

A separate RCMP spokeswoman responded to CTV's questions about the vacancy rate by pointing to the 1,088 cadets at Depot in Regina over the last year, a 175 per cent increase since 2012-13.

Taking into account a 13 per cent attrition rate, provided by the RCMP, about 947 cadets graduated this year. The Mounties project 800 members will depart this year, leaving a gain of nearly 150 people -- which won't go far to closing the existing gap.

Goodale’s spokesman says the RCMP Depot saw 36 troops of 32 cadets this year, which they hope "over time" to increase to 40 troops a year.

'It's not pocket change'

Pfleiderer said the RCMP doesn't know how many members leave for another police force.

"Regular members leaving the organization are not required to disclose details of new employment, if any," he said.

"However, our overall attrition (terminations and retirement) is quite low for 0-15 years of pensionable service. In fiscal year 2016-17, less than 1.5% of the RCMP Regular Member workforce left the organization with less than 15 years of service."

Conservative Senator Vern White, a former Mountie who also served as Ottawa police chief, estimates the RCMP is 1,500 officers short and finding it hard to recruit more.

But he's more concerned about how the short-staffed force will police national security and organized crime. Paulson told the Senate national security committee in 2016 that he'd had to move 470 people from white-collar crime to national security.

The vacancy rate at headquarters and at the national division, both located in Ottawa, are double that of those in the provinces and territories, Pfeiderer said, because the force is "focusing on the primacy of operations."

"Staffing front-line police officers has taken precedence over filling vacant positions in non-operational roles in Ottawa," he wrote.

White says that has an impact on the community.

"I'm not saying they can afford not to do that [counter-terrorism] work. I'm saying they can't afford to stop doing organized crime. National security is the new normal," he said.

The catch is the cost: White says he thinks it would take $1 billion for the RCMP to be able to balance both properly.

"It's not pocket change for sure."

The Mounties have made some changes to their application and recruiting process over the last few years to deal with the fact that they're just treading water when it comes to staffing. The application process is faster and more flexible, with broader entrance criteria, Pfleiderer said. They also introduced "an enhanced disability management and accommodation program" to help injured or ill members remain or return to work.

"Proactive recruiters continue to spread the message that we're hiring through their outreach work and we are planning an advertising campaign," he added.

The question for those dealing with the vacancies is whether it's enough. Smith pointed to the impact on the members' families.

"[My wife] finds it hard. She's a mother of two young children and she has a job and she can't rely on me to be home when I am supposed to, and it's very hard," he said.