A stomach-churning concoction of mashed-up garlic, wine and stomach bile that was used to treat eye infections over 1,000 years ago just might hold the key to killing antibiotic-resistant superbugs today, say British researchers.

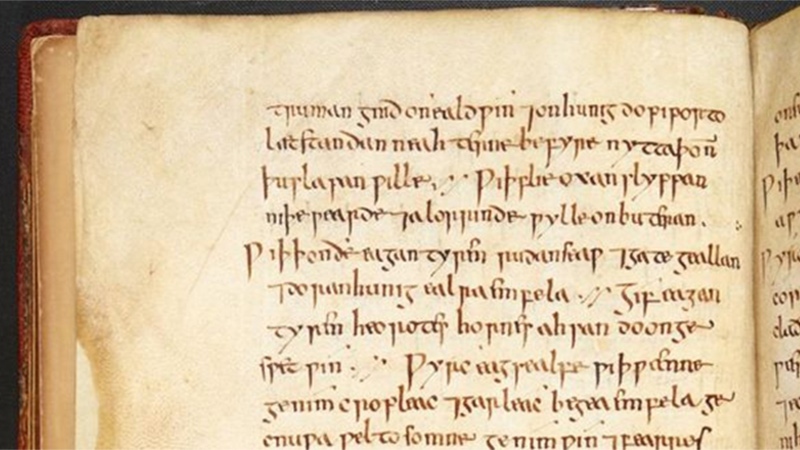

The discovery was made thanks to a curious Anglo-Saxon and Vikings Studies professor at the University of Nottingham, named Christina Lee.She wanted to test one of the strange-sounding potions listed in "Bald’s Leechbook," a 9th century textbook written in Old English that is preserved in the British Library.

So she enlisted the help of microbiologists from the university’s Centre for Biomolecular Sciences to recreate one of the recipes for treating styes, those annoying eyelash follicle infections.

To their amazement, the researchers found that the mixture was highly effective at wiping out MRSA, or methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, a bacterial strain that causes thousands of hospital-aquired infections. In fact, they say, it performed as well as, if not better than conventional antibiotics.

In order to recreate the recipe, the researchers had to grind together garlic with a variety of onion called cropleeks, along with wine and "bullocks’ gall," which is old-fashioned terminology for bile from the stomach of a cow.

The recipe said to let the mixture stand in a "brass vessel" for nine days, wring it through a cloth "and about night time apply it with a feather to the eye." As brass vessels were hard to come by, the team used glass bottles instead and added in squares of brass sheeting.

They then tested the resulting mixture on MRSA samples grown in a lab on human collagen. They also tested it on mice with MRSA-infected wounds.

To the researchers' astonishment, the mixture was able to kill off most of the bacteria in both models.

Interestingly, when they tested each of the ingredients alone on the bacteria, none had any effect. But when combined together as explained in the recipe, only one bacterial cell in 1,000 survived.

University microbiologist Steve Diggle says he was astonished to find the recipe worked.

“When we built this recipe in the lab, I didn't really expect it to actually do anything. When we found that it could actually disrupt and kill cells in S. aureus biofilms, I was genuinely amazed," he said in a statement.

Fellow microbiologist Dr. Freya Harrison says the finding is an important one, given the growth of antibiotic resistance and the lack of any new antimicrobial agents on the horizon.

She says her team is now seeking more funding to extend this "fascinating" area of research, looking to the past to find modern weapons against our most difficult pathogens.