For the first time in decades, it’s possible – however unlikely – that Canada could experience a nuclear attack from a rogue nation that appears eager to show off its military strength against our allies to the south.

It’s a doomsday scenario that has gone from unthinkable to remotely possible in just a few short years. Now, with North Korea boasting the ability to hit North America with a hydrogen bomb delivered via intercontinental ballistic missile, experts say such an attack could potentially miss an intended U.S. target and hit somewhere in Canada instead.

Fear of nuclear annihilation is nothing new to those who remember the Cold War tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, when there was constant dread in North America that Russia might suddenly launch a nuclear attack. But for millennials, this marks the first time during their lives when the possibility of a nuclear attack on home soil is serious enough to warrant public discussion.

CTVNews.ca spoke with several experts to pose the big question: What if? What if everything went wrong, and North Korea launched a nuclear missile strike against North America?

Detection

This July 4, 2017 file photo distributed by the North Korean government shows what was said to be the launch of a Hwasong-14 intercontinental ballistic missile, ICBM, in North Korea. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP)

Military personnel at NORAD and U.S. Northcom would be the first to detect an intercontinental ballistic missile launch from North Korea, likely through satellite observation, up to five minutes after liftoff. South Korea would also likely detect the launch and relay that information to the rest of the world, as it does during most North Korean test launches. From that point, the news would be forwarded to the White House and the United States would activate its emergency broadcasting system. Canadians working at NORAD would also be able to relay the message to the prime minister, although there would be no Canadian participation in the missile defence response. Essentially, the decision to shoot the missile down would rest entirely with the Americans.

Experts say, at that point, there’d be no telling which city the bomb was meant for, unless Kim Jong Un announced it himself. There would also be some question as to whether it can actually hit a specific target.

A missile aimed at San Francisco, for instance, could miss and strike the coast of B.C., according to Christian Leuprecht, a political science professor at the Royal Military College of Canada and senior fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute.

The Charlie crew, made up of U.S. and Canadian military personnel, work the night shift Jan. 18, 2006, at the NORAD command center in Cheyenne Mountain, Colo. (AP / Denver Post, John Epperson)

UBC political science professor Allen Sens says the Americans would attempt to intercept an incoming strike with their ballistic missile defences, regardless of whether they thought it was headed for Canada or the U.S. Such a response would likely be able to take out one or two missiles, but a dozen or so would be more than enough to overwhelm those defences and get a few missiles through.

And as many have pointed out, it only takes one missile slipping through those defences to cause a major disaster.

When does the public find out?

News of a missile launch from North Korea would likely spread as it has in the past. On Nov. 28, for instance, South Korea’s news agency was first to report a missile had been launched from the North, and the U.S. soon looked into the situation and confirmed it.

The first public notice of an ICBM suspected of hitting North America would likely be the activation of the American emergency broadcasting system, Sens says. After that, news would spread rapidly through social media and other traditional media platforms.

Such news would likely generate a wave of hysteria, especially since it would pose a blanket threat to whole areas of North America. A missile headed for the Pacific coast, for instance, could generate panic from Vancouver to Los Angeles, and everywhere in between.

Sens says it would be impossible to evacuate a targeted city, especially without knowing the power of the bomb on the incoming ICBM.

Clarity over the target would only come toward the end of the ICBM’s 30-minute flight time, Sens says.

“The later in the flightpath, the more your estimate of the footprint… of a nuclear strike begins to narrow,” he said.

For many individuals who would be affected by a nuke, the first warning they get would be the blinding flash of the actual detonation.

When the bomb explodes

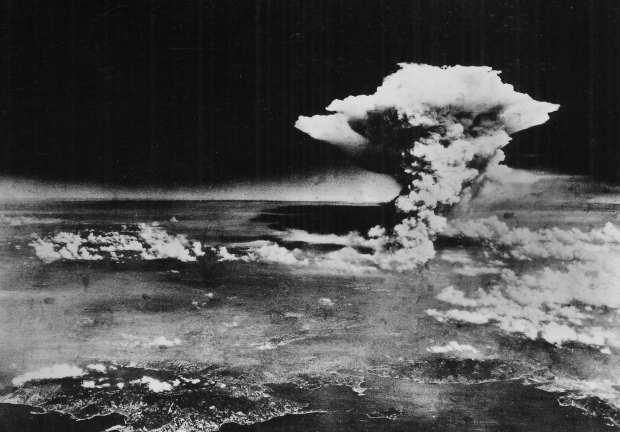

In this Aug. 6, 1945 file photo released by the U.S. Army, a mushroom cloud billows about one hour after a nuclear bomb was detonated above Hiroshima, Japan. (AP / U.S. Army via Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

North Korea’s ideal goal would be to detonate its nuclear warhead a few hundred metres above a target on the ground, to create the largest possible fireball and spread the fallout of radioactive dust and ash from the explosion.

Location, weather, wind direction, height of the blast and, most important, the explosive yield of the bomb all make it difficult to say exactly how far-ranging its effects would be. However, the website Nuke Map offers a handy tool for estimating the impact of explosions over any chosen location. The site is run by Alex Wellerstein, a Harvard-educated historian of nuclear weapons.

If, for instance, we use the maximum estimated yield of North Korea’s first suspected hydrogen bomb test – 100 kilotons, or the equivalent of 100,000 tons of TNT – Nuke Map estimates the resulting air blast over the heart of Toronto would cause nearly 214,000 fatalities and 294,000 injuries.

An identical explosion over downtown Vancouver would cause approximately 85,000 deaths and 288,000 injuries, but those numbers could double if the detonation occurred over a residential neighbourhood such as Riley Park, for example.

The nuclear fireball at the heart of such a blast would incinerate everyone within a 3-kilometre radius, according to data from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. Most of those within a five-kilometre radius would be fatally hit by the shockwave from the explosion, killed by asphyxiation or poisoned with deadly radiation sickness.

Beyond this, approximately half of those within a 10-kilometre radius would die of severe burns or physical trauma from the blast wave. Many others would die from the fires set by the explosion, or, eventually, from radiation sickness. Buildings closest to the blast would be obliterated, but sturdier concrete structures that are a few kilometres away might only suffer heavy damage. Homes would be completely destroyed, and debris would be sent flying through the air.

People and buildings caught in the fireball would be completely incinerated. Anything close to the fireball would be hit by a shockwave packing 20 psi of force – or roughly twice as much power as the wind of a strong tornado. The shockwave would grow weaker as it travels outward from ground zero, but many would still be burned by the intense heat, injured by flying debris or poisoned by deadly levels of radiation. Death is assured for the vast majority of people caught in the blast, although those on the edge might last a few hours or days before they die.

In this June 30, 2015 file photo, Sumiteru Taniguchi, a survivor of the 1945 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, shows his back with scars of burns from the atomic bomb explosion, during an interview at his office in Nagasaki, southern Japan. (AP / Eugene Hoshiko)

Even those who don’t feel the blast will probably see it from a distance, or experience it in the form of a massive electromagnetic pulse that can fry electronics for hundreds of kilometres in every direction.

Wind can make the damage caused by the bomb even worse, by blowing the radioactive fallout hundreds of kilometres across residential and rural communities in the area. This fallout not only poisons humans, but also leeches into the ecosystem, tainting soil, water, crops and livestock. These effects can last several years.

What can you do?

A nuclear attack sounds apocalyptic, but civil authorities still have advice for surviving such a doomsday scenario.

Whether you’re in Canada, the continental United States or Guam, where the North Korean threat is particularly acute, the guidelines for surviving a nuclear attack are the same. Essentially, experts say to take shelter the moment you hear that there are bombs in the air. Evacuation usually isn’t an option when missiles are already on the way, but you can use the precious minutes before they hit to insulate yourself against the blast.

A huge mushroom cloud rises above Bikini atoll in the Marshall Islands July 25, 1946 following an atomic test blast, part of the U.S. military's "Operation Crossroads." The dark spots in foreground are ships that were placed near the blast site to test what an atom bomb would do to a fleet of warships. (AP)

Authorities say three factors are key to survival: distance, shielding and time. In terms of distance, it’s easier to survive the blast the farther away you are from ground zero. When it comes to shielding, the goal is to put as much earth and concrete as possible between you and the nuclear blast, so that those thick walls can soak up the deadly radiation. And as far as time is concerned, it can take days or weeks for harmful radioactive fallout to clear. If you’ve got the resources to hunker down for an extended period of time, you have a better chance of outlasting the fallout cloud.

Canada’s nuclear preparedness guidelines from 1969 recommend keeping an emergency kit on hand with medical supplies, 14 days of rations, a battery-powered radio and a kerosene stove for preparing food. The guidelines also recommend familiarizing yourself with your community’s nuclear attack plan – if it exists – and establishing your own plan with your family.

Guidelines say that for those trapped outside, the best idea is to find a solid-looking brick or concrete structure and take shelter against it. One can also hide in a ditch or culvert and lie flat with the head covered, in hopes of surviving a blast that’s some distance away. Otherwise, the force and heat generated by such a blast can incinerate a human body or rip the skin right off of it, depending on distance from ground zero.

Keeping your head down is key, as the nuclear flash can blind you. It’s also important to remember that even if you’re a considerable distance from the blast, it can take several seconds for the blast wave to hit you. Stay covered until it has passed.

There are also plenty of hokey Cold War-era videos that teach H-bomb preparedness to children. They’d be adorable if they weren’t terrifying.

National response

Health Canada is designated as the leading government body in the event of a nuclear emergency, which includes a nuclear attack under Canada’s Federal Nuclear Emergency Plan. Public Safety Canada is slated to provide support for Health Canada, and both agencies are expected to work with existing provincial and municipal emergency plans in any location struck by an attack. B.C., for instance, has plans in place for responding to a mass fatality incident, while Ontario has detailed plans for addressing a nuclear meltdown or nuclear attack.

Experts say any domestic response would involve first responders from both sides of the border, as Canada and the U.S. have an agreement in place to call for help from one another in the event of such a disaster. However, it might take hours or days for crews to enter the blast zone of a nuclear attack, as they would have to wait for specialized equipment to arrive for protection against radioactivity. Fires and radioactivity might also delay their response time.

Mass evacuations are also to be expected in the path of the fallout cloud. The size and direction in which the cloud travels can be hard to predict, as it’s influenced by wind, the size of the nuclear explosion and the amount of debris generated by the blast. Such a cloud could travel hundreds of kilometres.

The environmental and humanitarian impact of a nuclear attack would generate much greater challenges that play out over days, weeks, years and even decades after an attack.

However, the immediate military response would happen much more quickly.

Military response

A North Korean attack would almost certainly be met with swift and severe military force from the United States but that does not necessarily mean full-scale nuclear war.

Instead, experts say the U.S. is more likely to use its ultimate non-nuclear weapon, the so-called “Mother of All Bombs,” to cripple the North Korean regime’s military and communications infrastructure.

In this May 2004 photo, a group gathers around a GBU-43B, or massive ordnance air blast (MOAB) weapon, on display at the Air Force Armament Museum on Eglin Air Force Base near Valparaiso, Fla. (Mark Kulaw/Northwest Florida Daily News via AP)

The Americans also would not be alone in their response, as NATO treaties and other agreements would kick in, prompting many countries – including Canada – to declare war on North Korea.

“This is partially why everyone wants to avoid an escalation,” Leuprecht said, adding that European countries such as Germany really don’t want to be pulled into the conflict.

“The Germans understand full well that if there’s a missile that flies toward North America, it’s going to be ‘all in,’” he said. “The last things the Germans want to do is start sending troops to somewhere in Asia to defend the North American homeland.”

Political science professor and international relations expert Elliot Tepper, of Carleton University, says the exact circumstances of such a conflict are difficult to predict, other than to say it would result in a huge death toll.

“The scenarios regarding the North Korea situation have been wargamed endlessly,” Tepper told CTVNews.ca.

“The possibility that we could find ourselves in a nuclear exchange does exist,” he added. “But it doesn’t have to be a nuclear exchange to be deadly.”

Why it probably won't happen

Tepper urges restraint when discussing the possibility that North Korea would ever actually use its fledgling nuclear arsenal.

“They never intend to use this except in an extreme circumstance,” he told CTVNews.ca. He says North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is interested in the survival of his regime, and is ultimately trying to use nuclear weapons as a bargaining chip to play tough with the international community. “It’s meant as a deterrent,” he said.

Sens echoed that sentiment, adding that it’s foolish to simply label Kim Jong Un a “madman.”

“Kim Jong Un is interested in survival, and based on that, their actions can be interpreted as rational to this point,” he said.

This story is part of a three-part series on the nuclear threat North Korea poses to Canada.