TORONTO - Did you know that our bodies are home to trillions -- yes, trillions -- of microorganisms that play a role both in keeping us healthy and making us sick?

Taken together, these teeming communities of bacteria, viruses and fungi make up what's known as our microbiome, and probing its secrets has become a red-hot area of medical research in recent years.

On Thursday, the country's scientific funding agency, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and several partners announced a $16-million investment for seven projects to see what role these microbes might play in a number of key diseases.

"We're starting to realize that there are many, many possibilities or linkages between our microbiome and disease that we would not have expected before, especially complex diseases," said Dr. Marc Ouellette, scientific director of CIHR's Institute of Infection and Immunity.

"This is really an emerging field where we think there are a lot of new discoveries to make that will have a direct impact in health."

Among the researchers receiving a five-year grant is David Guttman of the University of Toronto, whose team is studying how the bacterial, viral and fungal constituents of people with cystic fibrosis change as the disease progresses.

Cystic fibrosis, the most common, fatal genetic disease affecting Canadian children and young adults, is an incurable, multi-organ disease that primarily affects the lungs and digestive system.

"One of the big problems with cystic fibrosis is the production of a very thick mucus layer in the respiratory tract," Guttman said. "And that not only causes physical problems in breathing, but also makes a really nice environment for microbial communities."

"We know that CF patients very frequently, almost universally, are infected with very large amounts of bacteria and often fungal infections," he said. "So what is the role that they play? Are they actually causing these exacerbations of the disease?"

Guttman hopes genetic sequencing of the multitudes of different microorganisms that inhabit the respiratory tract and lungs in CF patients will bring forth the answer, although he concedes the process will take years.

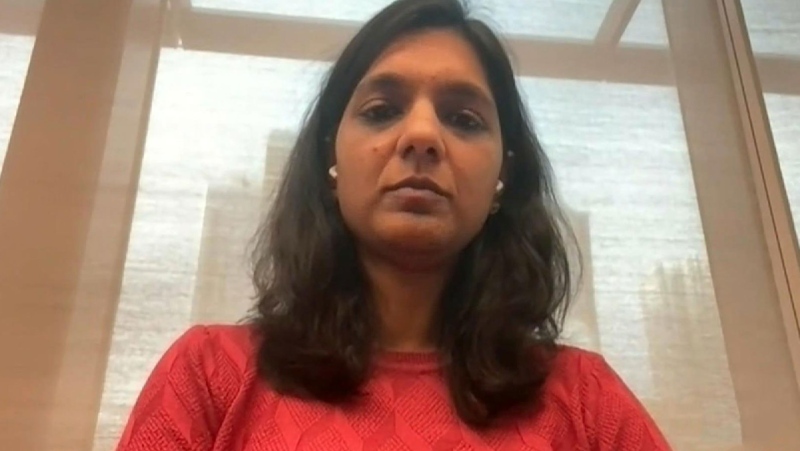

The Toronto geneticist is also involved with another microbiome project that received CIHR funding -- a multicentre project co-directed by Anita Kozyrskyj, an epidemiologist at the University of Alberta.

The cross-Canada team suspects that giving antibiotics to infants in their first year of life may be the underlying trigger that causes asthma and allergies to develop later in childhood.

Everyone has "good" intestinal bacteria, known as microbiota, to help absorb nutrients and protect against harmful bacteria. But antibiotics affect the microbiota, and studies show that by one year of age, more than half of Canadian children have been treated with one of the antibacterial drugs.

In a pilot study, Kozyrskyj has shown that infants given antibiotics by three months of age have definite changes in their microbiota.

"The number of different kinds of bacteria is less," she said in a release. "Now the question is: Does antibiotic use early in life change the microbiota in the intestines of children? And are these changes associated with the development of asthma and allergies in children? We are hoping to specifically pinpoint which 'bad' bacteria it is that is causing asthma."

In Vancouver, Dr. Deborah Money of the Women's Health Research Institute is leading a project to examine vaginal organisms to determine what a healthy bacterial balance is for women to protect against sexually transmitted infections and preventing pregnancy loss and pre-term birth.

Using advanced technology, the team will be able to rapidly sequence hundreds of thousands of the bacteria species.

"What's important about this approach is that we are not looking at a single bacteria in isolation," Money said in a release. "We are able to look at whole communities and how they interact with each other, which is critical to understanding how a woman keeps healthy, and to identifying when something is going wrong with her reproductive system."

For Dr. Ken Croitoru, a gastroenterologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, a $2.5-million CIHR grant will allow his lab to proceed with DNA sequencing of microorganisms in the digestive system that may play a role in the development of inflammatory bowel disease.

The research will involve sequencing the genomes of vast numbers of different microorganisms living in the intestines, extracted from biological samples taken from almost 1,500 people at high risk for Crohn's disease. The condition, which causes chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, has a strong genetic component.

"The idea here is not just that bacteria live in our gut and cause disease, but it's our body and our genetics that maybe allows for certain types of bacteria -- some good, some bad -- to interact and influence development of disease like Crohn's disease," Croitoru said in an interview Thursday.

"For example, if you're missing one gene, does that give you a different kind of bacteria that may lead you to be more susceptible to disease?" he said. "It may well be that it isn't a bad bacteria, but it's a collection of bacteria that normally are good. But yet in the person with the bad gene, those good bacteria behave badly."

The ultimate goal, said Croitoru, is to identify a cause of inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis so a preventive therapy or even cure could be developed.

"So this is the first step, and a necessary step, to really changing the way we deal with patients who have not just inflammatory bowel disease, but many of these complex diseases."