Exposure to even the tiniest amount of perfume, hairspray or pesticide floating in the air can make Marie LeBlanc sick. The Winnipeg photographer lives with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, a little-known but chronic condition affecting about three per cent of Canadians.

MCS sufferers can experience symptoms including burning eyes, headaches and skin rashes.

“You go into a building and everything is bothering you: the lights, the fumes -- everything,” she said in an interview with CTV Winnipeg.

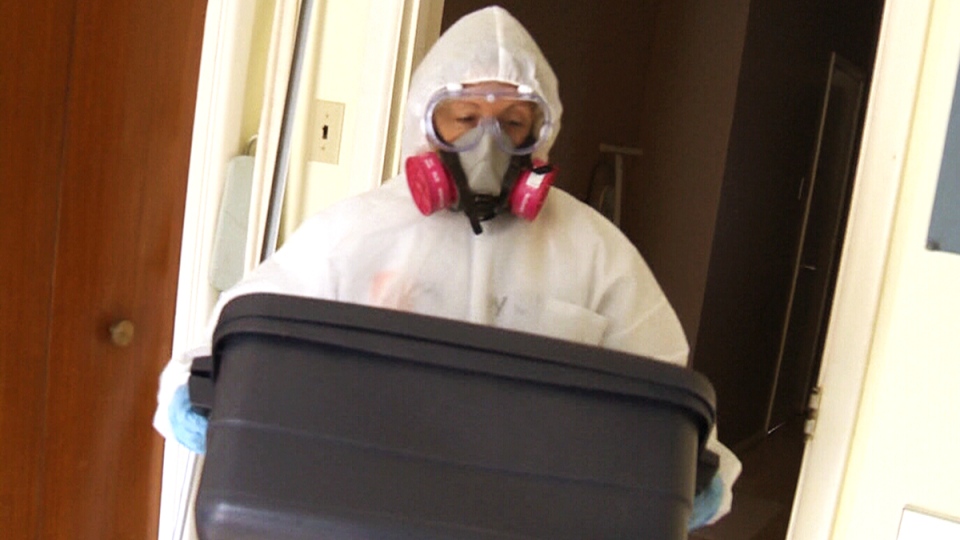

LeBlanc has had to go to extreme lengths to avoid chemicals that most people can tolerate without any adverse effects. The only way the 51-year-old is willing to step into her apartment is in a full-body protective suit.

Since late spring, LeBlanc has slept in a tent and stayed with family and friends in order to avoid her apartment.

Now, after living in the unit for three years, LeBlanc is moving out, without a permanent place to go.

LeBlanc said her doctor is helping her find a place to call her own, so she’s doesn’t end up on the street.

One of the problems, sufferers say, is that MCS is not recognized by the World Health Organization as a medical condition.

That means people like LeBlanc can face financial and housing hardships, with little community support.

But there are organizations that try to help people with non-diagnosable conditions.

The Integrated Chronic Care Service is one of them. The Nova Scotia-based facility treats “environmental sensitivities and complex chronic conditions, such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue.

Rob Dickson, a clinic co-ordinator at the centre, says the “big reason” why a condition like MCS is controversial is because there’s little evidence that can support the diagnosis.

He says many “mainstream conditions” can be diagnosed through medical tests, such as bloodwork, CT scans and MRIs.

“And with the conditions we work with, there are no diagnostic testing or bio markers that can show there is something going on within the body,” Dickson said in an interview with CTV News.

In 2011, LeBlanc travelled to the centre for her diagnosis and to learn how to manage the condition.

“What you’re looking for is what is affecting the person’s overall health,” Dickson said. “Ultimately is there is a physical component to it? Yes. Is there is a mental health component to it? Yes -- but I would also argue that this is for any type of condition that we experience.”

In an effort to destigmatize MCS, LeBlanc used her talent as a photographer to make a statement about her condition.

Earlier this year, she displayed her letters from doctors, as well as her photography for an exhibit on her struggle.

LeBlanc never attended the show, however. There were too many chemicals inside the studio.

Instead she spoke with guests using a computer.

The Manitoba Human Rights Commission says there is a legal obligation for employers and landlords to assess if accommodations can be made.

“Sometimes it may be unreasonable to accommodate a person’s needs, however, sometimes they can do something,” said spokesperson Isha Khan.

With a report from CTV Winnipeg’s Beth MacDonell