On the heels of World Refugee Day and protests by Canadian doctors who claim refugees are not receiving the most basic human health care, clinics on the ground face difficult decisions.

Sue Grafe, a nurse practitioner with the Hamilton Centre for Newcomer Health (HNCH), receives refugee patients who under current government law are ineligible for basic health care.

“I want (Canadians) to know it’s not about the extras, it’s about the basics that are being denied,” Grafe told CTV News.

In one example, a Hungarian woman who fled her home country and is waiting for her refugee hearing has learned that she is pregnant, but the staff at HNCH are unable to check her for a fetal heartbeat.

The woman is not eligible for insurance to cover an ultrasound, and she is not eligible for health care in Canada.

“We don’t know if it’s an issue of fetal demise, meaning that the baby has passed away,” Grafe said.

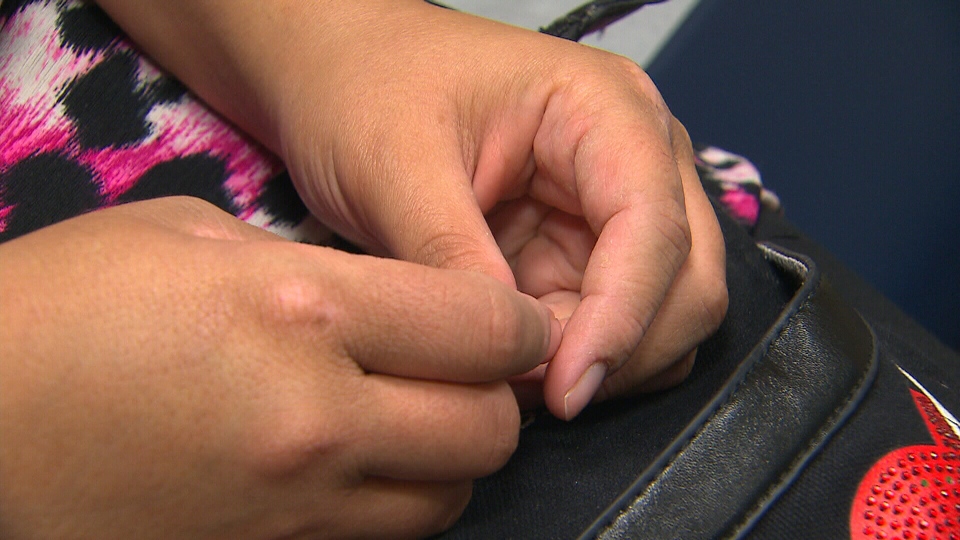

Through an interpreter the Hungarian woman said that she is sad and upset because she doesn’t know what is going on with her baby.

In June 2012 the federal government cut funding, leaving refugees who have filed a claim and are awaiting hearings without any health-care coverage.

“The reality is that the majority of asylum claims made in Canada are unfounded,” Ana Curic, a spokesperson for Minister of Immigration Jason Kenney, said in a statement.

“Canadian taxpayers funded free eye care, free dental care and free supplementary drugs for 4,000 asylum claimants from the United States. They did so for another 7,500 claimants from Hungary (prior to the June 2012 changes),” Curic said.

In December 2012, Immigration Minister Jason Kenney announced 27 countries, including Hungary, would no longer be considered for refugee claims, because those countries are considered “safe.”

Inside the Hamilton clinic, CTV found a 3-year-old girl and her mother, also Hungarian refugees, awaiting treatment. The mother said that both her legs were broken in Hungary, and the family was attacked because of their Roma background.

Nurses believe the little girl is a case of “failure to thrive,” which could mean allergies, or iron deficiency which could affect brain growth. Without blood tests or X-rays, nurses will not know for sure.

“We don’t know what will happen if somebody gets sick,” said the mother through an interpreter.

Earlier this week, doctors took to the streets in 17 cities across the country to protest against cuts to refugee health care.

“Even if you don’t agree with the immigration policies, we believe health care is a human right and we should be able to provide you with care,” said Dr. Christian Kraeker an internal medicine specialist and a volunteer with HNCH.

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip