A new Canadian study has concluded that a procedure to open narrowed veins in the neck and chest is ineffective in relieving the symptoms of multiple sclerosis and works no better than a placebo treatment. But some neurologists and MS patients who say the treatment worked wonders for them say more research is still needed.

The study, by researchers from the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health, was led by Dr. Anthony Trabousee, neurologist and UBSC associate professor of neurology. He says no further research needs be conducted on the theory of blocked veins and MS.

“We didn’t see any sign of a clear improvement across measurements to justify going forward with a larger confirmatory study. It’s done,” he told CTV News.

The findings have yet to be published, but were presented Wednesday at the Society for Interventional Radiology’s annual scientific meeting in Washington, D.C.

The study was conducted on 104 MS patients across the country. All had narrowing of either their jugular vein, which drains blood from the brain, or their azygos vein, which drains blood from the spinal cord. The patients were randomly chosen to receive either an actual venoplasty treatment. or a “sham” procedure.

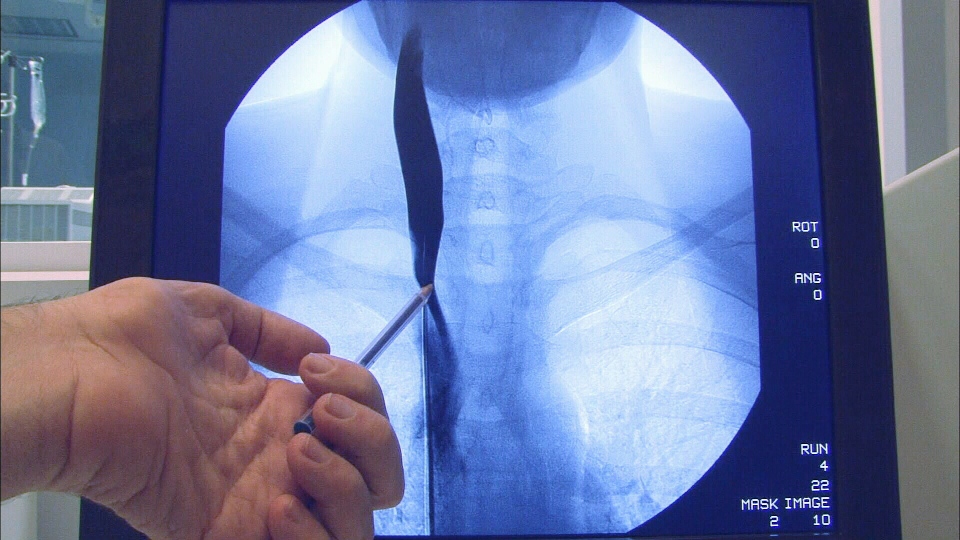

In the actual treatment group, doctors inserted a catheter into their blocked or narrowed veins and then inflated a balloon to push out the blood vessel’s walls. In the “sham” treatment group, a catheter was inserted in the vein but no balloon was inflated.

Neither the patients nor the physicians who evaluated them knew who was receiving the actual treatment or who received the sham procedure, making the study “double-blinded.”

The patients were evaluated for MS symptoms three days after the procedure and then at regular intervals for 48 weeks. MRI scans (magnetic resonance imaging) of their brains were used to look for new lesions in their myelin, the coating on brain neurons that erodes in MS patients, leading to symptoms such as numbness, walking difficulties and muscle weakness.

Patients were asked to evaluate their own symptoms, and to perform a limb function and cognitive function test called the MSFC (Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite).

In all, about 25 per cent of patients saw an improvement in their symptoms, but they were equally divided among the real and the sham treatment groups.

As well, by 48 weeks after treatment, the researchers report that patients’ disability symptoms were back to the baseline established at the beginning of the study. The brain scans also showed no statistically significant changes in either group.

The study findings have yet to be published, but they were presented Wednesday at the Society for Interventional Radiology’s annual scientific meeting in Washington, D.C.

The study authors conclude their findings represent “the most definitive debunking” of the so-called “liberation procedure.”

In 2009, Italian physician Dr. Paolo Zamboni published a study showing that venoplasty helped some patients with MS who had a condition he dubbed chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency,” or CCSVI, a narrowing of veins that causes improper blood flow from the brain.

Zamboni theorized that neck vein narrowing might cause iron to accumulate in the brain and spinal cord, triggering an autoimmune response.

'I got my life back'

MS patient Kathy Francis of Brockville, Ont. says she is stunned by the “negative tone” of the study’s results announcement in a news release. Both she and her daughter, who also has MS, had the venoplasty treatment in the U.S. and say it brought “fantastic results” that changed their lives.

“I am sitting there and I am reading that and I am thinking, wow, I had a complete turnaround. I got my life back from this,” she told CTV News, adding she felt better within days of the treatment.

“If I didn’t have this treatment, I would be paralyzed or in a wheelchair. That is where I was in 2010, in hospital. I couldn’t look after myself… I have had four years of my life gone because of relapses through MS.”

She says since she had the treatment, she no longer wakes up in the morning wondering if her legs or her arms are going to work. Today, she’s on the go every day, curling five times a week and playing with her grandkids.

“I got my balance back, my brain fog went away, the crawling inside my head went away. I can talk and I have had no relapses or symptoms since I had my treatment in 2012,” she says.

Francis also wishes the government had kept a registry for all MS patients who went outside of Canada to get treated and followed up with their results.

“Many of us have had positive results and we are not being talked about. It is all the negative; the positives are never put out there,” she says.

The study’s lead researcher, Dr. Anthony Traboulsee, says his team had hoped the study would show the treatment could work for some patients.

“We were attracted to the theory at the beginning. The idea that something could improve patients’ lives is very attractive. We had to do the science around it, and explore: ‘Is it true? Can we validate it?’” he told CTV News.

Traboulsee, the director of the MS Clinic at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health in Vancouver, says he is proud of the double-blind approach his team used, which helped eliminate any bias during the controversial procedure. He says he and his colleagues are disappointed the procedure did not have a positive result

“Patients with MS need something better to improve their quality of life. We are all motivated toward that goal. That’s why the study had to be done,” he said.

Given their findings, though, the authors say they hope their research will persuade MS patients not to pursue “liberation therapy,” which they say is an invasive and potentially expensive procedure that carries risks of complications.

Others who are analyzing the preliminary data say that they have concerns that patients enrolled were too advanced in the disease compared to other treatment trials, and that the balloon angioplasty may not have been performed to adequately restore blood flow.

“The question really is, (was) the patient selection appropriate, and was the technique of the procedure the way I would do it, or the way anybody who had evolved with the procedure since 2009 would do it,” Dr. Salvatore Sclafani, interventional radiologist from New York, told CTV News.

Sclafani said the study left him very “unsatisfied.” He questioned the size of the balloons used in the procedure, saying they “did not look very big.”

He added: “I think they probably underestimated the size of the vein, the degree of stenosis” and under-dilated the veins with balloons that were small.

“A lot of the balloons they used were not high-pressure balloons.”

Sclafani said in his experience, the balloons must be “very high pressure to open the veins.”

The study wasn’t supposed to be complete until September 2017.

The early presentation of the still unfinished trial caught Geoff McNeill of Langly, B.C., by surprise.

He has MS and was enrolled in the UBC trial -- awaiting his final assessments on whether the venoplasty worked. But he awoke to find the researchers had already reached a conclusion.

“Seems strange how they can announce it doesn't work when I'm not finished my trial?” he told CTV News

Mc Neill said after his first study procedure in June of 2015, he felt nothing. After the second procedure in May of 2016, he says ran up a few flight of stairs and ran around his house, feeling new-found energy. He doesn't know which session provided the actual venoplasty but he has his suspicions.

While some of the gains have since abated, he says he’s improved and is skiing again.

“I’m doing so well now, I bought a pass to Grouse and although I’m not as good as I was, I’m skiing and loving it again."

He says his story raises questions about the study and the so-called "definitive results" said McNeill.

Research continues

In an email to CTV News, Dr. Zamboni noted that 40 per cent of the patients in the Pan-Canadian study were in advanced stages of MS – primary or secondary progressive and who had MS for on average, 17 years.

”All the preliminary studies clearly showed that in this category (venoplasty) does not modify significantly neither (disability scores) EDSS nor MRI,” Zamboni wrote.

Other studies of venography in MS that showed a benefit, Zamboni wrote, were done in patients with relapsing and remitting MS (earlier stage of the disease) who had been diagnosed less than 10 years.

Another study on venoplasty for MS is underway in Italy called Brave-Dreams (BRAin VEnous DRainage Exploited Against Multiple Sclerosis) that will study an even larger group of patients.

Dr. Alireza Minagar, a U.S. neurologist who specializes in MS and teaches at Louisiana State University, says he has always been intrigued by the CCSVI theory and the idea that the venous system has been implicated as a possible cause. He thinks despite this study’s latest findings, the concept deserves further research.

“While still in its infancy, CCSVI poses an enormously complicated idea, which requires more fundamental studies to understand its role in pathophysiology of MS,” he said in an email to CTV News.

He says it isn’t clear if any of the opened veins in the UBC study closed up again after treatment, which is called restenosis, nor whether blood flow actually improved in the treated group.

He applauded the UBC group for tackling the study, but says the preliminary findings pose more questions that need to be studied.

“As a neurologist, I would suggest that the methods employed in this study be scrutinized more meticulously before ‘shelving’ this concept entirely, particularly when venous stenting approaches are increasingly being validated for other neurovascular complications.”

The study was jointly funded by the federal government’s Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the MS Society of Canada, and the provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba and Quebec.

With reports from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip

Below are slides presented by the UBC team at the Society of Interventional Radiology conference on March 8, 2017: