Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan appear to be growing old before their time.

An ongoing study at a U.S. Veterans Affairs hospital in Boston has found emerging evidence that even combat troops in their 20s and 30s are showing early signs of heart disease, slowed metabolisms and diabetes.

Researchers with a program called the Translational Research Center for Traumatic Brain Injury and Stress Disorders (TRACTS) have been testing U.S. veterans for the last three years to better understand the long-term effects of brain injuries and PTSD.

It’s well known that both these problems affect similar areas of the brain and can lead to cognitive and psychological problems, as well as substance abuse and mood disorders.

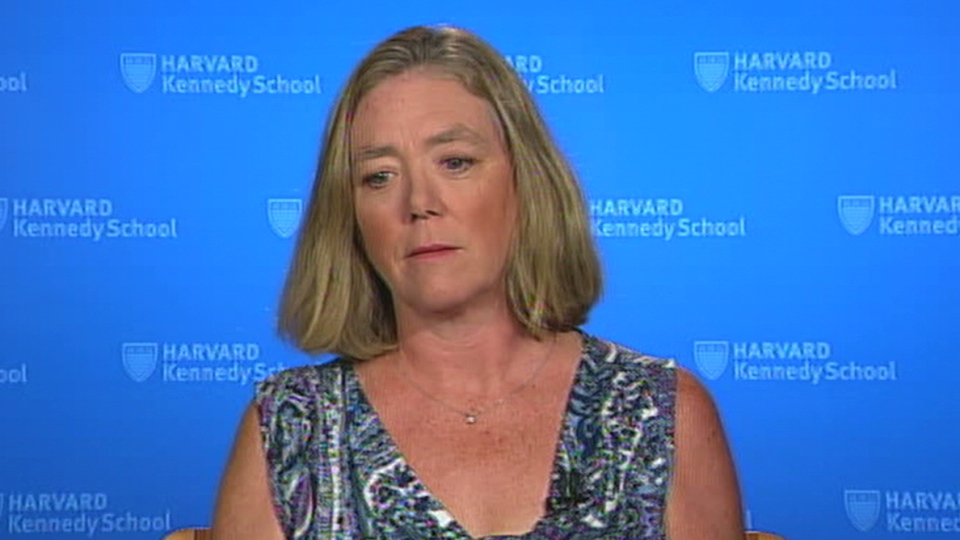

But what has really stunned the researchers are the physical problems these veterans are also experiencing, says Regina McGlinchey, a neuropsychologist and co-director of the study.

“The data are preliminary but what we are beginning to see is that there are a number of veterans and service members coming back who have elevated risk factors for what we would call ‘premature aging’ or cardiovascular disease,” she told CTV’s Canada AM from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“What that means is that we are seeing higher rates of hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetes, elevated glucose levels, hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol) in young adults that we really wouldn’t normally see until people are more advanced in their 40s and 50s.”

Those most at risk, the study suggests, are those who are also dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder and blast-related concussions.

Why soldiers and veterans who have seen combat seem to age faster than civilians is still not clear, McGlinchey says.

“There are a number of theories, and we’re really not in a position to tie down on any one particular mechanism. But the level of stress that our soldiers are under is certainly a factor,” she says.

It may be that living with a high level of stress for months at a time, facing repeated life-and-death exposures, starts to cause changes to the internal chemistry of people's bodies.

“Anyone who is exposed to these extreme conditions of both physical and psychological trauma – sometimes occurring in the same incident – are going to be at risk of developing these kinds of problems,” she says.

McGlinchey says it also appears that repeatedly being near explosions -- even when they don’t cause physical or brain injury – may also increase the risk.

“We are at the beginning of understanding what blast exposures do to the body’s physiology… even for sub-concussive events that don’t necessarily produce a traumatic brain injury,” she says.

“We need to know: What does it do to the physiology of the body to be exposed repeatedly to blasts?”

Of the 270 or so soldiers tested so far, about 30 per cent have signs of PTSD, and another 30 per cent have a traumatic brain injury along with PTSD. McGlinchey says they’ve also noticed that traumatic brain injury very rarely occurs on its own, without some kind of stress disorder.

Another 30 per cent of those recruited have had no long-term brain problems. These are the soldiers who are acting as controls in the study.

McGlinchey says her team does not screen ahead of time for PTSD among the study participants; the only requirement is that they have to have served in combat in either Afghanistan or Iraq.

Each of the men and women is subjected to more than 10 hours of testing, including blood tests, memory tests and neuropsychological tests to look for PTSD or anxiety disorders.

McGlinchey says that in many cases, this study is the first time that some of the soldiers have ever talked about their war experiences. And in many cases, they haven’t received a diagnosis of PTSD before entering the study.

The study has been underway for three years now and is scheduled to continue for another two. The hope is that by the end of the study, researchers will better understand the effects of repeated blast exposures and TBIs on soldiers and how these effects evolve over time.

“It’s going to be a big challenge and it’s going to take a lot of numbers to be able to tease out what happens and to see how these things interact with each other,” McGlinchey says.