For the first time, researchers have captured images of how LSD affects the human brain, showing how the drug alters brain activity.

Researchers from Imperial College London in the U.K., working with the Beckley Foundation, gave 20 healthy volunteers both LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) and a placebo. Researchers then used brain scanning techniques to see how LSD alters the way the brain functions.

Their results, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show what happened to the volunteers' brains as they experienced visual, dreamlike hallucinations often associated with the drug.

The researchers observed a difference in the brain's functioning under LSD compared with placebo.

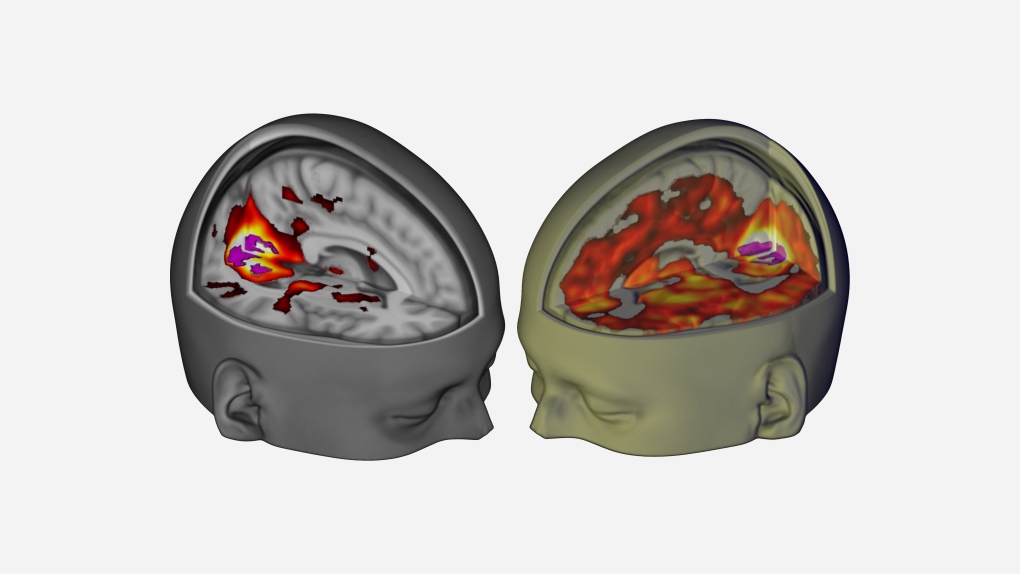

Under normal conditions, information from our eyes is processed in the visual cortex, a part of the brain located near the back of the head. However, when the volunteers took LSD, several additional parts of the brain became involved in the visual processing, the researchers found.

This image shows how, with eyes-closed, much more of the brain contributes to the visual experience under LSD than under placebo. (Photo from Imperial College London)

Lead researcher Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris said the team observed brain changes in the volunteers that suggested they were "seeing with their eyes shut."

"Albeit they were seeing things from their imagination rather than from the outside world," he said in a statement. "We saw that many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD – even though the volunteers' eyes were closed. Furthermore, the size of this effect correlated with volunteers' ratings of complex, dreamlike visions."

The researchers also observed changes in the volunteers under LSD, leading to a more "integrated" and “unified” brain.

Carhart-Harris said that normally the brain consists of "independent networks" that perform separate specialized functions, such as vision, movement and hearing. However, he said, under LSD the "separateness of these networks breaks down," leading to a more "integrated or unified brain."

He said that the results suggest the effect causes the "profound altered state of consciousness" that people often describe when using LSD.

"It is also related to what people sometimes call 'ego-dissolution,' which means the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world," Carhart-Harris said in the statement. "This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way – and seems to be associated with improvements in well-being after the drug's effects have subsided."

Carhart-Harris said that as humans grow up, their brains become increasingly compartmentalized, and they become more focused and rigid in their thinking. But, he said, human brains on LSD more closely resemble the brains of infants: free and unconstrained.

"This also makes sense when we consider the hyper-emotional and imaginative nature of an infant's mind," he said.

The study said that the findings represent an "important advance in scientific research with psychedelic drugs at a time of growing interest in their scientific and therapeutic value."

In 2014, a small pilot study found that LSD may help lower anxiety in patients with life-threatening disease, including cancer and Parkinson's disease.

During the 1950s and 60s, researchers explored the use of LSD in conjunction with psychotherapy. However, much of that research came to a halt when the drug was made illegal in the U.S. in 1966.

LSD is considered a controlled substance under Canada's Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.