TORONTO -- Researchers have produced lung cells in the lab using stem cells grown from the skin of patients with cystic fibrosis -- a tool they believe can be used to test drugs that might overcome the debilitating, life-shortening condition.

In a study published Sunday in Nature Biotechnology, researchers at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto describe how they produced what are known as induced pluripotent stem cells from skin taken from patients with CF.

Induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells, are adult cells that have been genetically manipulated in the lab to act like embryonic stem cells. As such, they can give rise to heart, muscle, liver and virtually any other cell type in the body.

In this case, the researchers wanted to make lung cells because it is the lungs that are primarily affected by cystic fibrosis.

One in every 3,600 children born in Canada has CF. The disease, which results from genetic mutations, causes a thick, sticky mucus to clog the lungs and airways, leading to repeated respiratory infections and lung damage.

The mucus also severely affects digestion: CF patients must take large doses of digestive enzymes at each meal so their bodies can absorb nutrients.

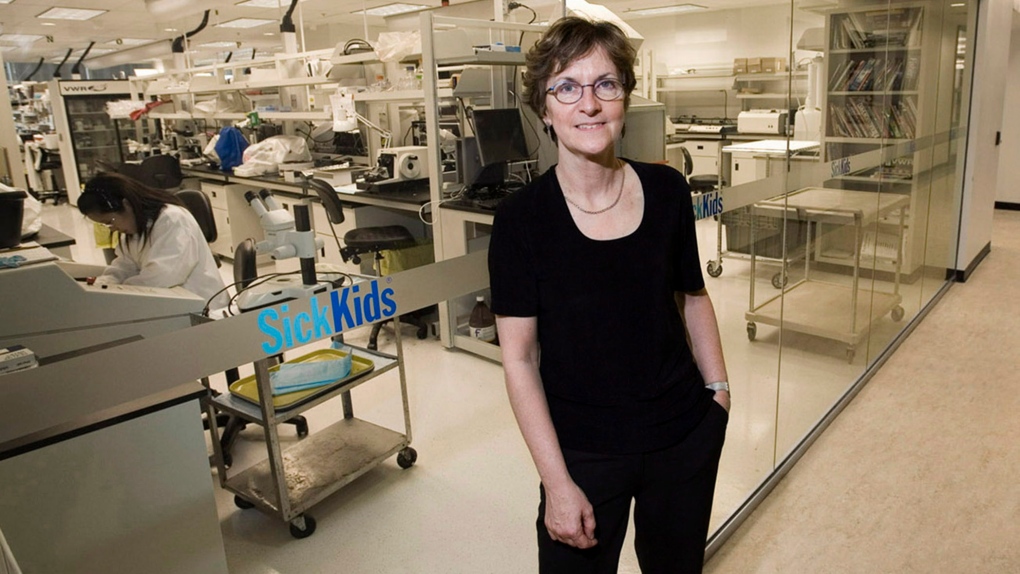

"What we would like to be able to do is take cells from patients, turn them into these iPS, or pluripotent cells, and then be able to turn them into lung cells that we can use to test for drugs that might help to treat cystic fibrosis," said principal researcher Janet Rossant, chief of research at Sick Kids.

Because a patient's cells all carry the genetic mutations that give rise to cystic fibrosis -- including the lung cells grown in the lab -- researchers can test drugs that specifically target the individual.

One of those drugs is an experimental compound currently being tested in the lab to see if it can reverse the effects of a key mutation in cystic fibrosis, which involves a gene known as CFTR.

The CFTR gene was isolated at Sick Kids in 1989 by a team led by Lap-Chee Tsui.

"This study shows the major impact stem cell research can have on the field of individualized medicine," said Rossant. "It is a promising move toward targeted therapy for patients with cystic fibrosis."

If researchers can generate lung cells derived from a particular patient, then they can look for a specific drug that will work in that individual's cells.

Then, if the drug is effective in overcoming the mutation in lung cells in the lab, the next step would be to see if it works in the patient, she said.

"What we are trying to do here is not take lung cells and put them back in patients -- that's a ways off. But by taking these cells and growing them in culture, we really do have, in this fairly short term, new cells that can be used to develop drugs that might be used to treat patients.

"In the long run, if we could improve the efficiency of making these lung cells, and really get them to function, one day we might indeed be able to use them to help repair damaged lung tissue."

Up until recently, the only therapies available for patients with cystic fibrosis have targeted symptoms of the disease, such as respiratory infections and digestive disorders, rather than the CFTR gene mutation itself.

Lung transplants can prolong life, but a shortage of donor organs means that therapy is available to relatively few CF patients. One person dies from cystic fibrosis in Canada each week, and of the 40 who died of the disease in 2010, half were under 26 years old, according to statistics from Cystic Fibrosis Canada.

"More recently there has been a paradigm shift and now drugs are being developed to target the mutant CFTR specifically," said study co-author Christine Bear, co-director of the SickKids CF Centre.

"However, every patient is unique, so one drug isn't necessarily going to work on all patients with the same disease," Bear said in a statement.

"Take cancer, as an example. Each individual responds differently to each treatment. For some, a certain drug works and for others it doesn't. This tells us that we need to be prepared to find the best option for that individual patient."