The current whooping cough outbreak in New Brunswick continues to grow, with an increasing number of children and adolescents implicated.

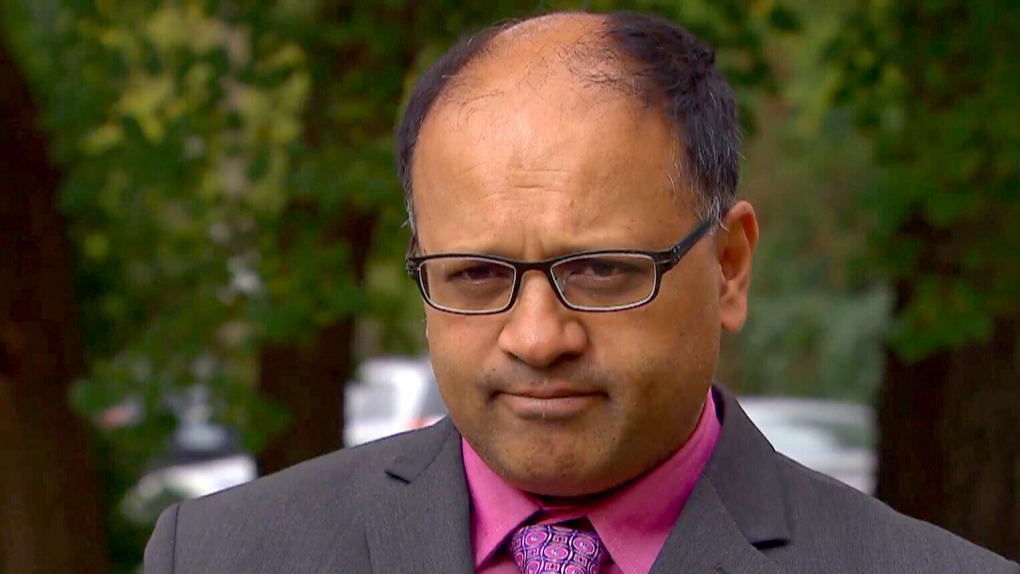

According to Dr. Yves Leger, Medical Officer in the Eastern Region of New Brunswick, which is at the centre of this outbreak, most people who have whooping cough symptoms have been vaccinated.

Another outbreak in Northern Alberta and Saskatchewan earlier this year similarly involved fully immunized populations. By contrast, an Ontario outbreak in 2012 involved unimmunized Mennonite communities, leading to the death of three infants.

Given the mixed history of outbreaks, some have concluded that so-called “anti-vaxxers” are to blame for the recent New Brunswick outbreaks of whooping cough, also known as pertussis.

Although I am a strong proponent of vaccination, the anti-vaxxer explanation is incorrect. Here’s why:

Some facts about pertussis and its vaccine

-

Pertussis continues to circulate among adults and adolescents, even in communities with high immunization levels. For infants under three months of age, pertussis remains a potential killer. But for adults and adolescents, the disease mimics a common cold, or at worst, causes a bad cough illness. In fact, the early phase of pertussis features a runny nose, and is indistinguishable to most doctors from other viral infections, including the common cold. Pertussis in older children and adults is often so mild that patients don’t seek medical attention. And when they do, the special tests needed to pick out the disease are seldom performed, and the patients are sometimes misdiagnosed as having something else, such as asthma. In short, most cases of whooping cough in older children and adults stay under the radar because they are inconsequential.

-

Protection from the pertussis vaccine falls over time. This is why five doses are required in childhood, along with “booster” doses in adolescence and adulthood to maintain protection. In contrast, most who receive the measles vaccine have life-long protection, explaining why measles does not circulate much amongst vaccinated populations.

-

The whole cell pertussis vaccine was replaced by the acellular pertussis vaccine in 1997, as the latter had fewer side effects. By 2012, it was becoming evident that the change in vaccine came with a trade-off: the acellular vaccine -- which contains only part of the pertussis bacterium -- has become less effective. A credible explanation is that the evolution of circulating pertussis strains are missing a protein called pertactin. Pertactin is an important component of the vaccine; if a strain is deficient in this protein, those who have received the vaccine are less able to mount an immune response to such strains. Multiple other outbreaks of pertussis in fully immunized children and adolescents have followed in the U.S. and Western Europe over the past three years. I suspect that the current New Brunswick outbreak falls into the same category, and may feature pertactin-deficient strains.

- Despite the shortcomings of the acellular vaccine, we remain miles ahead of the prevaccination era of the 1940s, when four times more cases of pertussis were reported. The current vaccine is still effective – just not 100 per cent effective. Better vaccines are the subject of research.

What should parents know?

Vaccinate mothers in pregnancy

As mentioned earlier, infants are the most vulnerable to pertussis and are therefore the greatest focus of prevention efforts. Unfortunately, infants have “immature” immune systems that do not provide good protection from the pertussis vaccine, which can’t be given until two months of age. The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) now recommends that pregnant mothers receive the vaccine between 27 and 36 weeks with every pregnancy. The Canadian recommendations, updated in February 2014, differ and suggest vaccination of pregnant women in regional outbreak settings, but not as a routine. Will this change given the emergence of whooping cough outbreaks across Canada?

Create a 'cocoon' for the infant

Since infants under the age of three months do not have good direct protection from the vaccine, immunizing adults who are in contact with infants with a single dose of the TdaP vaccine -- which protects against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussi -- is recommended. This would apply to those who work in child care, emergency rooms and pediatric wards, as well as parents and grandparents. Vaccination for adults in these categories is not funded by provincial health programs, but is relatively inexpensive.