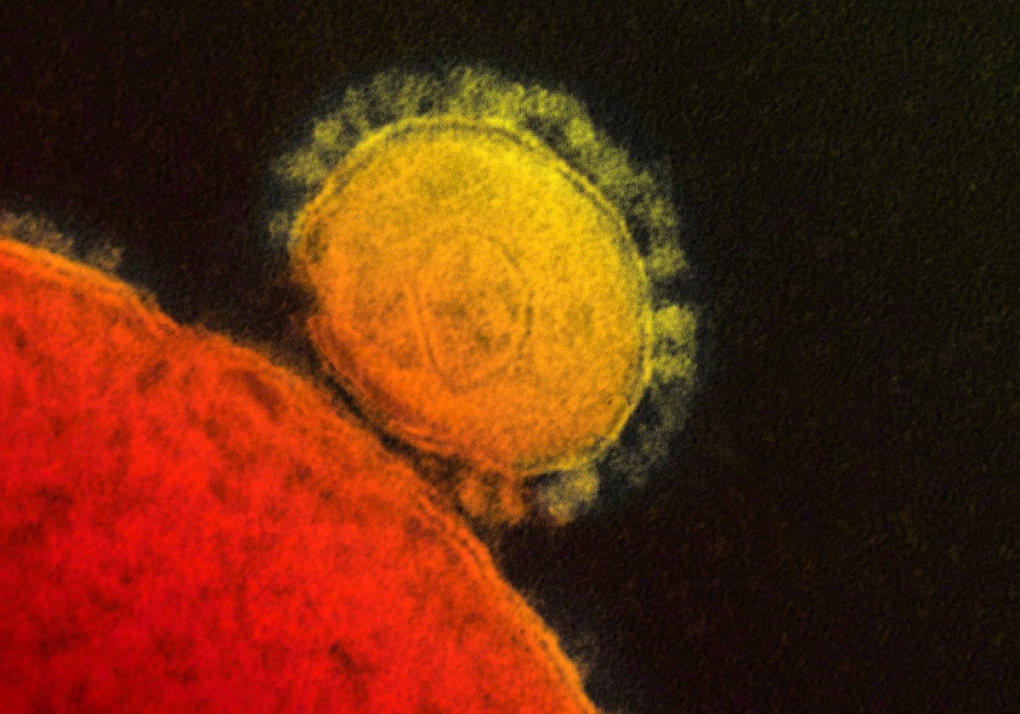

TORONTO -- Scientists from Italy are reporting having engineered a MERS virus that could be used in a vaccine, the second announcement in recent days of progress toward a preventive shot for the new coronavirus.

The developments will likely generate hopeful headlines and may create impressions that if MERS starts to spread globally a vaccine might be quickly available to help combat the new virus.

Don't bet on it.

It would take at least five to 10 years to make and test a MERS vaccine, get it approved by drug regulatory agencies and scale up production to the point where a commercial product is widely available, experts in vaccine development admit. And at the moment, it's not at all clear any company would take the financial risk involved in pushing a MERS vaccine project past the early scientific phases.

"There's a long way to go from showing in a research laboratory that you've got a potential candidate vaccine to actually producing a bottle of that vaccine that is going to be used or stockpiled," says Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the national school of tropical medicine at Baylor School of Medicine in Houston, Tex.

"Our technical ability to make (experimental) vaccines has sort of outpaced our social and political and economic infrastructure to figure out how to do this."

In fact, developing a vaccine to prevent infection in camels or whatever animal turns out to be transmitting the virus to people may be a more realistic and rapidly achievable goal, some experts following the MERS situation suggest.

Animal vaccines are far cheaper to make. Getting them through the approval process is also substantially easier than persuading regulators like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or Health Canada to green light a new vaccine for use in people.

"The first commercial West Nile vaccine for horses was licensed two years after the introduction in the U.S. of the virus (in 1999)," says Dr. Tom Monath, a vaccinologist who is a founder of One Health Initiative, an organization that focuses on the intersection of animal and human diseases.

"We still don't have a human vaccine. I mean, we have an experimental human vaccine, but nothing approved."

In the early days of a new disease threat -- like SARS in 2003 and its viral cousin MERS now -- scientists race to try to figure out how to design vaccines or drugs to prevent or cure the infection. Progress in those efforts is often trumpeted via publications in scientific journals and press releases from the academic institution or institute where the work was done.

But just because a vaccine can be made doesn't mean it will be. After all, vaccines aren't just health aids -- they are products. And producing them has to make economic sense.

"Companies don't make big investments in bringing forward new vaccines just because they think somebody might want it someday," says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

After the lab scientists and biotech companies lay the scientific groundwork for a new vaccine, they typically look for a partner with pockets deep enough to finance expensive rounds of clinical trials needed to apply for a licensure application.

"It costs roughly $200 million to $500 million to do that," Monath says of the costs of developing a vaccine. "That's really a low-ball estimate. Many vaccines cost $1 billion or more to develop."

The only players with that kind of dough are governments -- more on that option later -- and Big Pharma. But major pharmaceutical companies only push through their pipelines products that will sell.

"If there's a market, things get made," says Monath, who is a former chief scientific officer for vaccine maker Acambis, where he oversaw development projects on vaccines for C. difficile, West Nile virus and smallpox, among other diseases.

So rotavirus vaccines, which prevent a common diarrheal disease that afflicts rich and poor children around the world, make it to market. But if you want vaccines to protect against deadly Ebola viruses -- which trigger sporadic outbreaks that infect scores of people in some of the poorest countries of the world -- the math doesn't add up.

"There has to be a substantial demand," explains Osterholm. "That's why today we've not seen the commercialization and licensure for example for either of an Ebola virus or something as common as West Nile virus."

Childhood vaccines are a solid business because new customers are born every year. But to date, MERS fits more firmly into the Ebola model. It has infected around 130 people in four countries on the Arabian Peninsula over an 18-month period.

Its future path cannot be predicted, which is another strike against the business prospects of a MERS vaccine. While the virus could explode out of the region, as SARS did from Hong Kong, it could chug along in the way it has been so far -- infecting small numbers of people in a few countries. Or, like SARS, it could melt away.

If, as people fear, it spreads from Saudi Arabia when several million Muslims disperse back to their home countries after next month's Hajj pilgrimage, vaccine won't be in the medicine kit.

"Vaccines are slow-moving boats," says Hotez. "You could accelerate it so it's not going to take a decade. But it's not going to be done in two years either."

Osterholm and Monath both support the idea that developing a vaccine for camels -- or steering the current vaccine work toward an animal product -- would make more sense. That is, of course, if it's shown that camels are actually involved in the spread of the virus to people. To date the evidence is persuasive, but not proof positive.

Monath says, in general, more use should be made of animal vaccines to protect people. If horses don't contract Hendra virus from bats, for instance, they cannot pass the virus to trainers and others who have contact with horses. (Hendra infections have occurred in Australia.)

But Hotez points out that option will only work while MERS is still an animal virus that occasionally jumps into people. If it takes off and starts spreading person to person, it will be too late to try the animal vaccination approach.

Dr. John Treanor thinks the various obstacles shouldn't stop efforts to develop human MERS vaccines, saying work done now would help if the world needs a vaccine later.

Treanor, who is chief of infectious diseases at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, N.Y., suggests a MERS vaccine might be the type of product governments might want to develop and stockpile, in the way the U.S. government has done with smallpox, anthrax and H5N1 bird flu vaccines.

Still, most governments cannot afford such expensive emergency supplies. And even those that can may choose not to spend scarce funds on an expensive tool they may never need.

It all adds up to an iffy prognosis for MERS vaccine.

Says Monath: "I think we'll see whether the problem justifies the response, in this case vaccine development. It will take some time to know. But you have to be very cautious about promising vaccine in a short time frame on the human side."