An offshore publishing company accused of disseminating junk science and duping researchers has taken over the publishing of several respected Canadian medical journals, a joint CTV News/Toronto Star investigation has found.

Researchers and editors are sounding the alarm about a company called OMICS Group Inc., saying it could hijack the Canadian journals’ names and reputations.

OMICS, a Nevada corporation with headquarters in India, purports to offer hundreds of “leading-edge,” peer-reviewed medical and scientific journals on its website. It also claims to work with thousands of “esteemed reviewers” and scientific associations around the world.

But in August, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission filed a lawsuit against OMICS, alleging that the company is “deceiving academics and researchers about the nature of its publications” and falsely claiming that its journals follow rigorous peer-review protocols.

OMICS operates under the open-access model, which makes scholarly articles freely available to readers online. Many other open-access publications, such as PLOS, have great reputations and a proven track record of rigorous peer review processes. But OMICS has attracted controversy around the globe.

Even before the FTC launched its lawsuit, critics have accused OMICS of being a so-called “predatory publisher,” by leading inexperienced researchers to believe their work is being vetted by well-respected scientists and academics.

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of predatory publishers around the world, and they are seriously compromising scientific research, experts say.

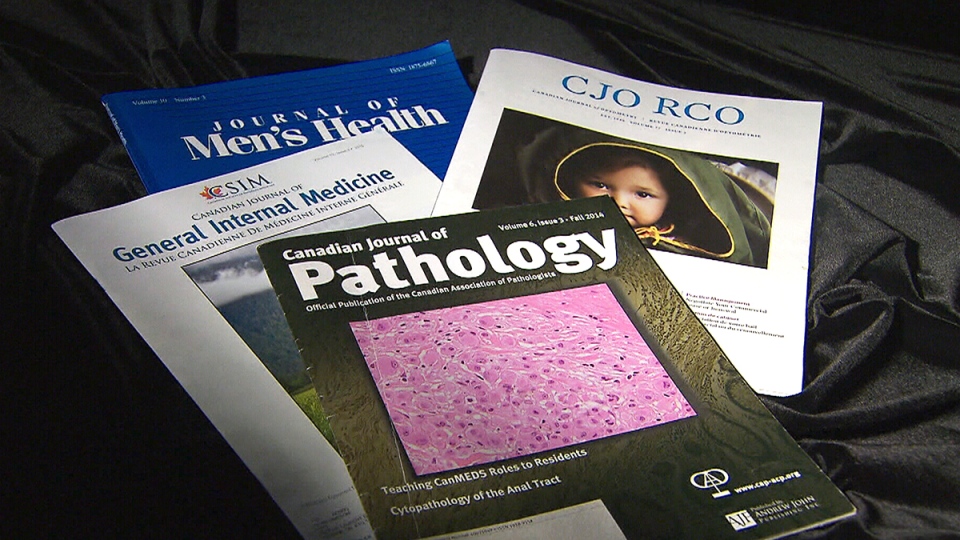

OMICS purchased two Canadian medical publishing companies this year: Andrew John Publishing and Pulsus Group. Their publications include journals such as Plastic Surgery, the Canadian Journal of Pathology, the Canadian Journal of Optometry and the Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine.

The pathology, optometry and general internal medicine journals have all moved to different publishers since the OMICS purchase.

Rose Simpson, the former managing editor of the Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine, said that after the OMICS deal was announced in January, she went on the company’s website and immediately noticed red flags as she started browsing through the journals.

“There were all kinds of typos, the grammar was wrong,” she said in an interview from Ottawa. “In medical journals, everything has to be accurate -- every comma, every word -- so that was my first suspicion.”

Simpson said she was eventually told that all operations and publishing work would be moved over to India -- including her job. Shortly after that, she was hired directly by OMICS, but decided to quit and start warning doctors and medical societies when she realized that OMICS was being sued by the FTC.

“This is a foreign company that has a questionable reputation that has bought up Canadian companies and is using their names as a front for whatever activities they are doing, which are not necessarily above board,” she said.

Simpson, who has been working with doctors and researchers for years, said many of them work tirelessly to conduct their research and spend countless hours analyzing it “for the betterment of the Canadian public.

“If they deal with a company that is not reputable then their manuscript becomes not reputable and they have wasted their time with their research,” she said.

‘False promises’

Experts say the proliferation of unchecked or bogus research ultimately poses a danger to patients, in cases where fake science ends up influencing health-care decisions.

The danger with junk science flooding the web is that looking up information on immunization, for example, may lead people to anti-vaccination articles in fake journals that are not based on real research, said Suzanne Kettley, a founding member of the Coalition for Responsible Publication Resources.

“So you can only imagine somebody (saying): ‘I found this article that was published in a scientific journal so therefore I don’t have to have my children vaccinated,’” she said.

Kettley, who is also the executive director of Canadian Science Publishing, a non-profit scholarly publisher, said predatory publishers may also use fake journals to promote certain agendas, such as publishing bogus research that says climate change isn’t real.

The FTC lawsuit states that, since at least 2009, OMICS has published hundreds of “purported online academic journals” with little to no peer review – expert evaluation of the research which is the gold standard in science and medical publishing.

The FTC alleges that OMICS claims to have prominent academics on its editorial boards, while in reality, many of those “editors” have never agreed to be affiliated with the journals published by the group.

The FTC suit also alleges that OMICS invites researchers around the world to submit papers for publication, but does not tell them that they must pay “significant” fees until after the article has been accepted.

“The defendants in this case used false promises to convince researchers to submit articles presenting work that may have taken months or years to complete, and then held that work hostage over undisclosed publication fees ranging into the thousands of dollars,” Jessica Rich, director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, said in a news release issued in August.

“It is vital that we stop scammers who seek to take advantage of the changing landscape of academic publishing.”

The FTC also alleges that OMICS has falsely advertised academic conferences around the world, telling paying attendees that prominent researchers will be among the speakers, when that is not the case.

Jeffrey Beall, a prominent academic librarian in the U.S. who has been keeping his own list of alleged predatory publishers, said he’s not surprised that OMICS is moving in on Canadian publications.

“Canada is an especially good country to break into because the scholarly publishing industry there is well respected,” he said.

Beall said Canadian scientists should be “extremely worried.” He alleges that OMICS exploits authors by demanding high fees to publish their research without vetting it and also promotes junk science.

OMICS responds

OMICS has denied allegations against the company listed in the FTC lawsuit and elsewhere, calling them “baseless” and “completely wrong.” In a letter to the FTC, the company’s lawyers demand that the U.S. agency “drop all the proceedings against our client.” You can read the company's 228-page response to the FTC lawsuit here.

In an interview, OMICS International CEO and managing director, Srinubabu Gedela, reiterated that allegations against his company are “completely false.”

“We are getting huge support from the scientific community for our open-access journal,” he said, speaking from Hyderabad, India. “All the allegations we are getting are from Western countries…and from a few publishers as well as their agents.

“We are disrupting their business by making scientific information open access and we are fighting for that,” he said, adding that the company’s profit margins are “less than 5 per cent.”

He said the OMICS website has millions of visitors who can access the publications for free. “That’s the beauty of open access.”

Gedela said OMICS now runs about 700 open-access journals and 3,000 conferences in 25 countries. He claims the company has “support” from about 50,000 editorial board members around the world and publishes more than 50,000 articles every year.

But one Canadian researcher listed as being on the editorial board of the OMICS journal Surgery: Current Research said he has never reviewed any articles for OMICS.

William Jia, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia’s Brain Research Centre, said he was invited to be an editor at the surgery journal and agreed, but never ended up doing any work for OMICS.

He now says that if there is a problem with the peer-review process at OMICS, he would like to remove his name from the editorial board.

“I don't want to be associated with that,” he said.

In an interview, Gedela denied allegations that OMICS-run journals publish articles that have not been peer-reviewed.

Gedela also said that OMICS staff will only do web hosting, PDF formatting and design for the newly acquired Canadian publishing groups.

“There is no control on content and editorial practice of Pulsus Group journals,” he said in an email before the interview.

The former publisher of Pulsus Group, one of the Canadian companies acquired by OMICS, said that only the Pulsus name was sold, “not the corporation itself.”

In an email, Robert Kalina said the Canadian medical journals themselves were not sold to OMICS either, and they are still owned by their respective medical societies, which control and review the editorial content.

Kalina went on to say that the medical societies don’t have to agree to OMICS’s publishing terms.

“And yes, all the societies knew as soon as the deal was concluded that OMICS was the purchaser,” he said in the email. “From what we understand, those that were disturbed by this publisher are moving to a new publisher, which they have every right to do.”

‘Zombie journals’

In some cases, the chief editors of affected journals have resigned. Others are trying to wrestle control away from OMICS.

Some of the journals that terminated their publishing with OMICS include the Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine, the Canadian Journal of Optometry and the Canadian Journal of Pathology.

Dr. Stephen Hwang, the president of the Canadian Society of Internal Medicine, which owns the Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine, said the society has taken steps “to ensure that the journal remains under our control and with full scientific integrity.

“As soon as we were alerted to the fact that (OMICS) had purchased these two publishing companies, we moved immediately to sever our connection with them and terminate our contract,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Hwang, who is also the director of the Centre for Urban Health Solutions at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, said publications run by predatory publishers are becoming “zombie journals.”

“Their scientific integrity is dead,” he said. “They keep shuffling along, publishing papers and people need to know that they are no longer the journal that they used to be.”

Some Canadian scientist and doctors, such as Dr. Madhukar Pai, are all too familiar with predatory publishers’ tactics.

Dr. Pai, Canada Research Chair in Epidemiology and Global Health and a professor at Montreal’s McGill University, said he receives several emails “every single day” from

predatory open-access journals. They ask him to submit papers, often on topics that have nothing to do with his expertise.

“This is a huge scam that is going on in the publishing world,” he told CTV News.

Dr. Pai said he has been a “big advocate” of open-access publications, but scammers have found a way to exploit and corrupt the concept.

Some publications will accept and publish “any garbage that we submit … so long as they get their cheque or their money,” he said. “They don’t care about science.”

Dr. Pai said he’s not really worried about savvy Canadian doctors and scientists falling for predatory publishers’ tactics, but he is concerned about companies such as OMICS taking over Canadian publications.

“It really pisses me off that this can even be happening in Canada,” he said.

This story is still unfolding, with scientists across Canada scrambling to find a solution. Some are trying to cancel their journal contracts or find new publishers.

In the meantime, they want to warn the public that some publishers are now using the good name of Canadian journals to damage scientific research.

The infiltration of predatory publishers threatens to destroy “the sacred trust” that doctors, academics – and the general public – have in reputable journals, said Simpson, the former editor of the Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Companies such as OMICS are “making a laughing stock of research and journals in general around the world,” she said.

With a report from CTV’s medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip and The Toronto Star’s Marco Chown Oved