Canadian women can first undergo screening for cervical cancer at a later age and have it done less frequently than currently recommended, according to new national guidelines issued Monday.

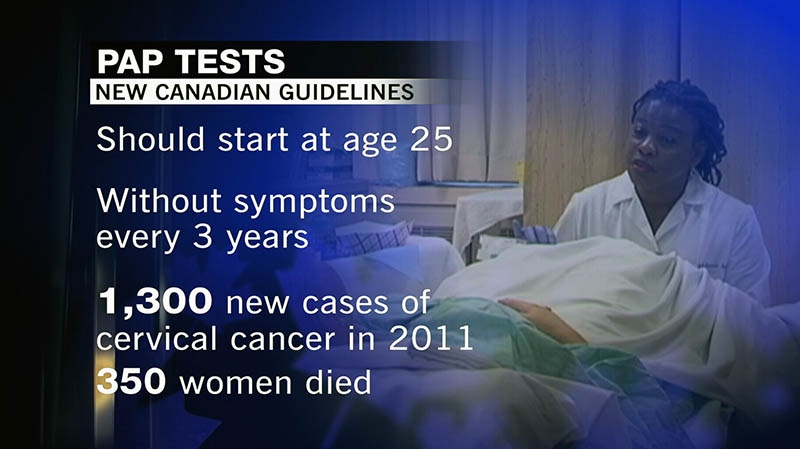

The guidelines, issued by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, suggest women should first be screened at age 25 and then only every three years until age 69. Currently, many doctors advise women to have a Pap smear every year, usually at the time of their annual physical.

"Every three years will do the job,” Dr. James Dickinson, task force chair and a professor of family medicine at the University of Calgary, told The Canadian Press. “Doing it every year doesn't really add very much (protection) but it adds a lot of inconvenience and some harm.”

In a note to clinicians, the task force said screening every three years leads to between 80 per cent and 90 per cent protection against cervical cancer, with more frequent screening offering little additional benefit.

The task force noted that it found “no benefit” to screening women under the age of 20 and little between the ages of 20 and 24 because cervical cancer is extremely rare in younger women. While younger women are at an increased risk of having abnormalities detected by a Pap smear, many of these will heal on their own and never threaten the woman’s health. Despite this, many young women with abnormal Pap tests are subjected to further testing and treatments that can cause harmful side effects, such as difficulty with pregnancy.

Under the new guidelines, women aged 70 and older no longer have to be screened if they have had three consecutive negative tests.

The new guidelines are published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The task force is a government-funded but independent panel that reviews the latest research and develops guidelines for preventive health care. The group’s last set of guidelines for cervical cancer screening were developed in 1994.

According to information released by the task force, an estimated 1,300 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2011. The disease kills approximately 350 women each year.

Incidences of cervical cancer rise significantly after age 25, with the most cases being diagnosed in women in their 40s. The group noted that routine screening is most effective for women aged 30 to 69, due to the increased cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates and lower risk of potential harm.

What the guidelines don’t include, however, is a recommendation that testing for the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) be done in conjunction with Pap tests to screen for cervical cancer. Research has proven that HPV can play a role in the development of the disease.

The task force said there is still “limited (though increasing)” evidence for HPV testing as a method for screening, and so will not make a recommendation until more data becomes available.

In Ontario, new provincial guidelines for cervical cancer screening suggest that HPV tests be the primary screening method for cervical cancer. In the case of a positive HPV test, a Pap smear would be conducted to confirm the findings.

Dr. Joan Murphy, who was head of the committee that developed Ontario’s new guidelines, said the province has yet to make the funding available that would allow the switch, in which case testing would be done every five years.

The Ontario guidelines also recommend screening for a broader age group, from 21 to 70.

Murphy said it’s not a serious concern that jurisdictions would differ slightly in their recommendations.

"I think for consumers, whether they be health-care professionals or the public, it's always easier when things are concordant,” Murphy told The Canadian Press. “So there is an unfortunate element. But it's not a disaster.”