Family members of Canadians with dementia are asking the Liberal government to reconsider plans for an assisted-dying law that won’t allow people to consent in advance to a medically assisted death.

Caron Leid has been caring for her mother Marlene Leid for 16 years. She has watched her deteriorate to the point where she is still alive, but unable to speak and at risk of choking, seizures and pneumonia.

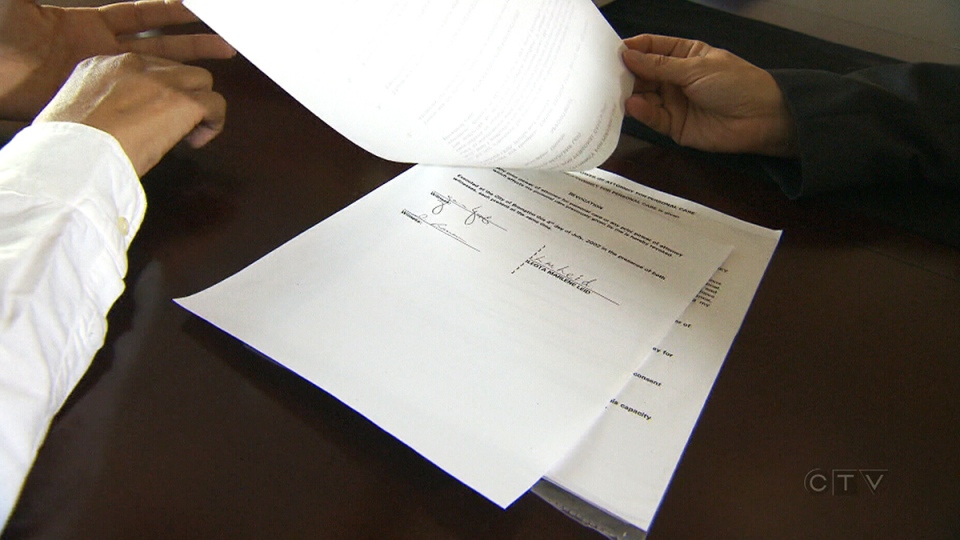

Leid said that her mother, a registered nurse, “knew that it would eventually get to this point … where there is zero quality of life” and that’s why she signed a “living will” in 2002. The document allows Leid and her brother to carry out their mother’s wishes on issues such as whether to insert a feeding tube, should her dementia reach a point that her body “forgets how to swallow.”

Leid said she is frustrated that the Liberal government’s proposed legislation won’t allow people like her mother to sign an “advance directive” that could have ordered an assisted-death at such an advanced stage of her mother’s disease.

“She wouldn’t want to go on like this,” Leid said. “It’s just impacting everybody. It’s like a long goodbye.”

Shanaz Gokool, CEO of the advocacy group Dying with Dignity, said she is hearing from many families going through the same thing.

“It is incredibly frustrating and disappointing that the government has drafted legislation that’s going to exclude potentially thousands and thousands of Canadians who will be suffering from dementia,” she said.

But others, including University of Toronto health law expert Trudo Lemmens, say that allowing advance directives would “open the door to abuse.”

Lemmens said the newly proposed law is correct to exclude advance directives, because the government must balance the right to die with concerns for vulnerable people.

“People with dementia are very vulnerable,” Lemmens said. “They cannot express a change in their opinion about a life-ending action that they may have agreed to on paper.”

The Supreme Court of Canada struck down the ban on medically assisted death last year, forcing the federal government to come up with new legislation.

The Liberals proposed last month that assisted death be allowed for consenting adults in "an advanced stage of irreversible decline" from a serious and incurable disease, illness or disability, for whom a natural death is "reasonably foreseeable."

The children of Kay Carter, who was a central figure in the court case, have expressed concerns that she wouldn't have been eligible, because she was suffering intolerably from pain but wasn’t close to a natural death.

Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould said that the legislation “finds balance between personal autonomy and ensuring that we protect the vulnerable and put in the necessary safeguards."

With a report from CTV National Medical Correspondent Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip, and files from The Canadian Press