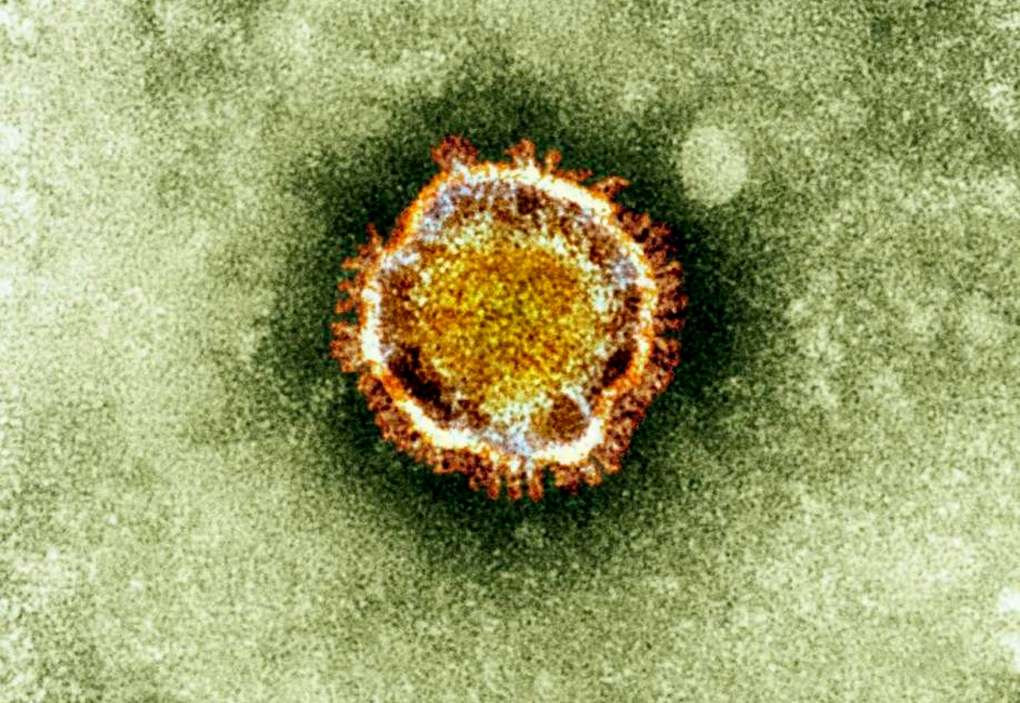

TORONTO -- A new Canadian-led study shows South Asia may be particularly vulnerable to importation of the MERS coronavirus, based on international air traffic patterns.

And in fact lead author Dr. Kamran Khan says the volume of travel between MERS source countries and low and lower-middle income countries raises questions about whether the virus may already be in nations that are not well equipped to detect or contain it.

Khan says there may be international blind spots where MERS could gain a foothold, moving in unnoticed by national health authorities or the global community.

Khan and colleagues from Canada, the United States and Britain published their analysis of airline traffic out of the four MERS source countries in the journal PLoS Currents Outbreaks.

They report that nearly 17 million travellers flew on commercial flights out of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates during the six-month period in 2012 running from the month before Ramadan to the month after the major pilgrimage, the Hajj.

While Muslims make pilgrimages to the holy sites of Saudi Arabia all year long, the volume of pilgrims is highest in the periods around Ramadan and the Hajj.

Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting, is currently underway; it runs until Aug. 7 or 8, depending on the waning of the moon. This year the five-day Hajj will take place in mid-October.

Khan, an infectious diseases specialist at Toronto's St. Michael's Hospital, uses International Air Transport Association data to plot the movement of air travellers as a way of predicting the possible spread of diseases. The association's data captures 93 per cent of commercial air traffic and it uses market intelligence to produce estimates for the remainder of the traffic.

He notes, however, that many international pilgrims to the Hajj travel via unscheduled charters which do not show up in this database. But he and his colleagues can estimate a country-by-country breakdown of Hajj pilgrims based on the formula the Saudi government uses to allocate visas for the pilgrimage. Each country is granted a number of visas based of the percentage of its population that is Muslim.

Showing the patterns of travel in and out of these four countries -- the only ones so far where people have been infected with MERS from its as-yet-undetected source -- helps countries figure out how vulnerable they may be to importation of the new coronavirus, Khan said Friday in an interview.

The analysis highlights reasons to be concerned about the possibilities for global spread of the virus.

"I think one of the things that was quite important to find here is that in contrast to SARS, where a lot of the cases ended up going to the world's industrialized countries, here the majority of travellers and of pilgrims are coming from low and lower-middle income countries where the capacity to detect imported cases in a timely manner might be limited ... (and) responding and controlling potential transmission is going to be far more limited," he warns.

Just over half of the travellers went to eight destinations: India, Egypt, Pakistan, Britain, Kuwait, Bangladesh, Iran and Bahrain. And of the 1.74 million foreign pilgrims who performed the Hajj last year, about 65 per cent were from low and lower-middle income countries.

During the period, nearly 97,000 people travelled to Canada from the four source countries. Canada sent an estimated 3,548 pilgrims to the 2012 Hajj.

Of the 90 confirmed cases of MERS so far, 71 have originated in Saudi Arabia. While all cases link back to the four source countries, cases have popped up -- and triggered limited onward spread -- in Britain, Tunisia, Italy and France. As well, two infected people travelled by air ambulance to Germany seeking care.

Khan says given that only about seven per cent of travel from the source countries went to the four countries that imported cases, it seems statistically unlikely that infected people haven't taken the virus elsewhere as well. For instance, 27.7 per cent of the travellers flew to Bangladesh, Pakistan and India during that six-month period last year, he says.

"And this sort of raises the question in our mind: Are there potentially cases already there but we actually just don't know about it? And maybe the country isn't aware that there are cases there," he says.

"In many previous outbreaks we've been able to see that look, the correlation between the movements of people and the movements of disease. They align quite nicely. Right now in the case of MERS, they don't align in the way that we would expect to see them align."

It is conceivable that cases could be missed. In the worst infections, MERS triggers a severe pneumonia that can be fatal. But while the death rate among known cases is high -- 50 per cent -- not all cases experience that degree of lung devastation. And infections with many bacteria and viruses can develop into pneumonia. In fact, hospitals don't always find the source of the infection when they treat people with pneumonia.

"It's something we should probably be mindful of, that there may be places where this virus could fly under the radar for a period of time," Khan says.

"That ... could have very significant local implications to countries. And then subsequently if the disease were able to gain some momentum locally, that of course could have international implications as well."