Around five years ago, 31-year-old Chantelle Petersen had a bad fall, and couldn't get up.

But it wasn't the first time. The native of Peterborough, Ont., had been falling a lot, and had no idea why.

But after meeting with her doctor, the graduate student at Trent University found out that she might have Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, widely known as ALS.

"I was in quite a bit of shock ... so much so that it didn’t quite register (and) I still went to class that day and broke down there," she told CTV News.

Petersen later received the confirmation that she had the neuromuscular disease, and since then the life that she had just started to carve out for herself has been thrown into disarray.

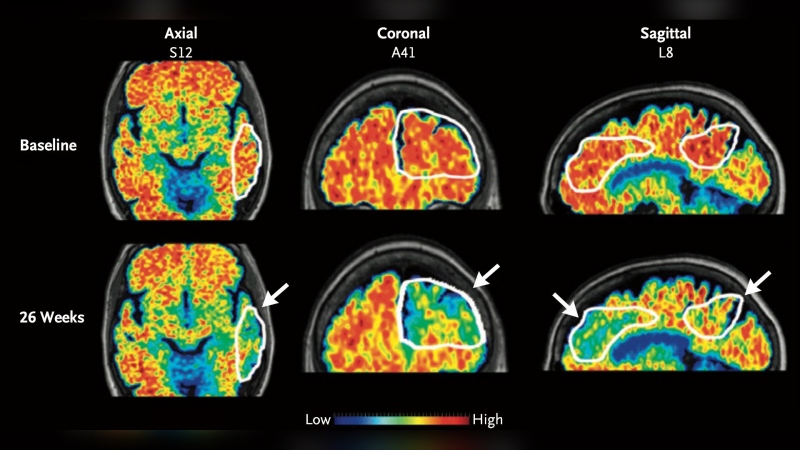

ALS, or Lou Gherig's disease, is a progressive illness that kills nerve cells and paralyzes muscles. The disease is fatal, and there is currently no effective treatment or cure. More than 4,000 Canadians live with ALS, and it usually strikes in middle and late adulthood. But it is not uncommon for young people to be affected by the disease, and new studies by the ALS Society of Canada are investigating whether the number is increasing.

"We see it quite frequently -- it’s not a rare thing to have young people diagnosed with ALS," said David Taylor, the director of Research at the ALS Society of Canada.

"We are currently going through a number of research studies to try to understand whether or not the number of young people is increasing, and we also have a national registry run out of the University of Calgary."

The disease carries an enormous financial cost.

And that burden may be the most difficult to handle for these young people who are just hitting their stride.

"What we find is that a young person who is diagnosed with ALS in their twenties and thirties are just starting out in life … this (diagnosis) will obviously throw everything into disarray and unfortunately then there is a huge burden not only economically for those families, but also emotionally," said Taylor.

And that was case for Petersen, who says she can no longer walk or get out of bed by herself, and requires help to shower and eat.

The 31-year-old was also forced to drop out university because she has trouble using her hands and can't type.

"It is not easy on my family, everybody has been pulling together to make sure I can make it, and it is hard," said Petersen.

"I try not to think about what I have lost. I try and think about what I still have, which is great friends and family," she added.

Taylor says that the young people who have been diagnosed with the disease are often in precarious financial positions as they are just beginning their careers, and may have student loans, a new mortgage and young children.

He added that these problems are compounded by the fact that people with ALS can expect to pay an average $30,000 per year to cover the costs of home renovations, transportation, palliative medication, home care and equipment.

In addition to these direct costs, Taylor says that there often is a loss of income from family members who are forced to quit their jobs, or cut down on their work hours, and stay home to provide care for their loved ones.

"On average, the loss of income is over $50,000 a year per person, so … over a couple of years you are talking about … hundreds of thousands of dollars that a young family will lose.”

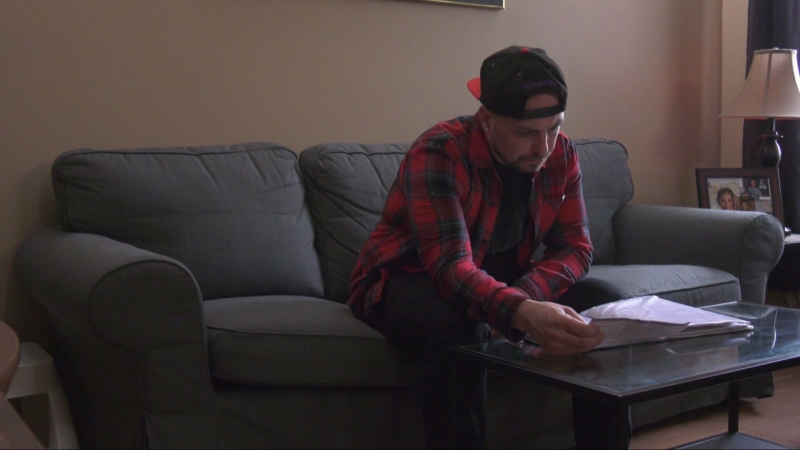

Petersen's husband, Philip Green, helps care for his wife, and is trying to start a computer-based business so he can work from home.

Green says that while there are support services for seniors and retirees, there is little available for young people with the disease. And for Green, who is still dealing with student debts, that means sometimes bills get pushed to the back burner.

"I see which bills literally have to be ignored because we have no money for them. I think, ‘How long can I defer this payment? How long can this be held back? Do I have to really ask one of my family members to help with this when they have done so much?'" Green said.

"I most definitely get scared, mainly that I am not going to be able to support … Chantelle in what is needed financially, emotionally," he added.

To help families cope with the disease, the ALS Society is pushing Ottawa for more compassionate care benefits, which would allow caregivers to stay home longer.

Caregivers and loved ones of people with a terminally ill disorder are currently entitled to six weeks of benefits.

The non-profit is hoping to boost that period to 35 weeks, so that families have more of a financial buffer.

"ALS is a disease that can't wait (and) there are no effective treatments to slow down or stop the disease at this point, so … what we can do is help those vulnerable young Canadians … to move forward in a productive and high quality of life way ," said Taylor.

"For every year we put off any programs like this, you will have more and more Canadian families -- young families – who are going to be put into poverty," he added.

With a report from CTV’s medical specialist Avis Favaro and senior producer Elizabeth St. Philip