WASHINGTON -- U.S. government health experts said Thursday there are few reasons to continue using metal-on-metal hip implants, amid growing evidence that the devices can break down early and expose patients to dangerous metallic particles.

The Food and Drug Administration asked its 18-member panel to recommend guidelines for monitoring more than a half-million U.S. patients with metal hip replacements. The devices were originally marketed as a longer-lasting alternative to older ceramic and plastic models. But recent data from the U.K. and other foreign countries suggests they are more likely to deteriorate, exposing patients to higher levels of cobalt, chromium and other metals.

While the FDA has not raised the possibility of removing the devices from the market, most panelists said there were few, if any, cases where they would recommend implanting the devices.

"I do not use metal-on-metal hips, and I can see no reason to do so," said Dr. William Rohr of Mendocino Coast District Hospital, who chaired the meeting.

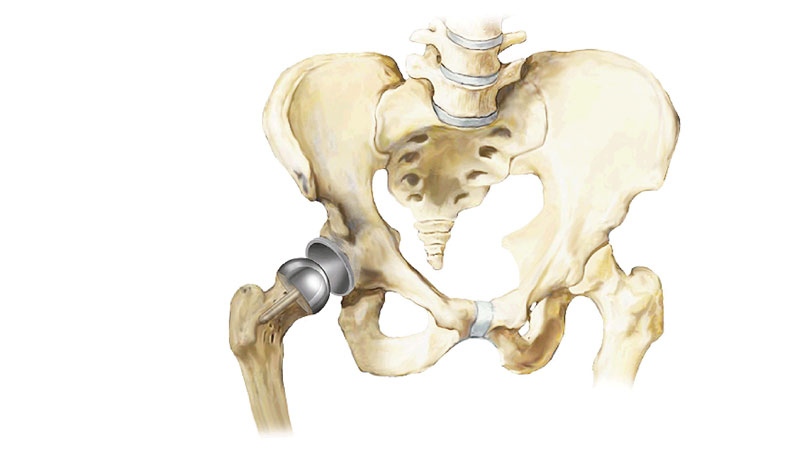

For decades nearly all orthopedic implants were coated with plastic or ceramic. But in the last 10 years some surgeons began to favor all-metal implants, after laboratory tests suggested the devices would be more resistant to wear and reduce the chances of dislocation.

But recent data gathered from foreign registries shows the devices fail at a higher rate than older implants. That information comes on top of nearly 17,000 reports to the FDA of problems with the implants, which sometimes require invasive surgery to replace them.

The pain and inflammation reported by patients is usually caused by tiny metal particles that seep into the joint, damaging the surrounding tissue and bone. The long-term effects of elevated metal levels in the bloodstream are not clear, though some studies have suggested links to neurological and heart problems.

About 400,000 Americans get a hip replacement each year to relieve pain and restore motion affected by arthritis or injury. Metal hips accounted for about 27 percent of all hip implants in 2010, down from nearly 40 percent in 2008. Doctors have begun turning away from the implants amid several high-profile recalls, including J&J's recall of 93,000 metal hips in 2010.

FDA's experts said Thursday that patients complaining of pain and other symptoms should get regular X-rays and blood testing for metal levels. However, panelists pointed out the problems with the accuracy of blood tests and the difficulties of interpreting the results. There are no standard diagnostic kits for sale that test for chromium and other metals

For patients who are not experiencing pain, panelists said annual X-rays would be sufficient to monitor their implants.

If the FDA ultimately follows the group's advice, U.S. recommendations would be less involved than those already in place overseas.

Earlier this year U.K. regulators recommend that all people who have the implants get yearly blood tests to make sure no dangerous metals are seeping into their bodies.

FDA regulators have suggested they want to take more time to sort out the differences between various implants and patient groups before making recommendations.

"The truth is there are different types of hips and different types of patients," said Dr. William Maisel, FDA's chief scientist for devices, in an interview last week. "Understanding the characteristics of patients who experience adverse events is very important."

Women and overweight people are among the groups that are more likely to have an implant failure.

With little definitive data on U.S. hip implants, the agency has asked manufacturers like Johnson & Johnson, Zimmer Holdings Inc. and Biomet Inc. to conduct long-term, follow-up studies of more than 100 metal-on-metal hips on the U.S. market.

FDA scientists say the studies will help "fill in the blanks" on a number of scientific questions, including the long-term effects of metal particles.

But public health advocates say it could take a decade before that information is available.

"Keeping these metal-on-metal hips on the market for the next five to 10 years while research is conducted is not ethical," said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Research Center for Women & Families, during a public comment session at the meeting. "If the companies want to sell metal-on-metal hips, they should be required to prove their safety first."