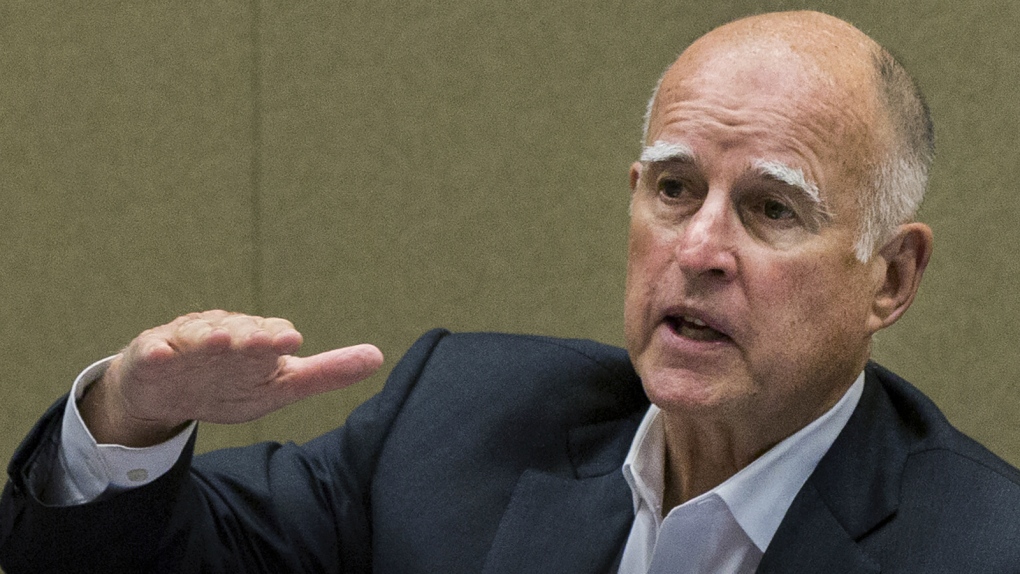

SACRAMENTO, Calif. - Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation Monday allowing terminally ill people in the nation's most populous state to take their own lives, saying the emotionally charged bill forced him to consider "what I would want in the face of my own death."

Brown, a lifelong Catholic and former Jesuit seminarian, said he acted after discussing the issue with many people, including a Catholic bishop and two of his own doctors.

"I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill," the governor wrote in a signing statement that accompanied his signature.

The 77-year-old Democratic governor said he would not deny those comforts to others.

The statement was Brown's first comment on the bill, which makes California the fifth state to allow terminally ill patients to use doctor-prescribed drugs to end their lives. The measure applies only to mentally sound people and not those who are depressed or impaired.

State lawmakers passed the bill last month. A previous version failed earlier this year despite the highly publicized case of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old California woman with brain cancer who moved to Oregon to end her life.

The measure was brought back as part of a special session intended to address funding shortfalls for Medi-Cal, the state's health insurance program for the poor. The law cannot take effect until the session formally ends, which probably will not happen until at least mid-2016.

Maynard's family attended the legislative debate in California throughout the year. Her mother, Debbie Ziegler, testified in committee hearings and carried a large picture of her daughter.

In a video recorded days before Maynard took life-ending drugs, she told California lawmakers that the terminally ill should not have to "leave their home and community for peace of mind, to escape suffering and to plan for a gentle death."

Religious groups, including the Catholic Church, and advocates for people with disabilities opposed the measure, saying it legalizes premature suicide and puts terminally ill patients at risk for coerced death.

Opponents said they were disappointed that the governor relied so heavily on his personal experience in his decision.

As someone of wealth with access to the world's best medical care, "the governor's background is very different than that of millions of Californians living in health care poverty without that same access," the group Californians Against Assisted Suicide said in a statement that warned of doctors prescribing lethal overdoses to patients who might not truly want them.

The bill includes requirements that patients be physically capable of taking the medication themselves, that two doctors approve it, that the patients submit several written requests and that there be two witnesses, one of whom is not a family member.

At least two dozen states introduced right-to-die legislation this year, though the measures stalled elsewhere. Doctors in Oregon, Washington, Vermont and Montana already can prescribe life-ending drugs.