Olana Tansley-Hancock was just eight years old when she had to start eating her meals in her bedroom because the sound of her family eating drove her mad.

- Scroll down or click here to vote in our poll of the day

“I can only describe it as a feeling of wanting to punch people in the face when I heard the noise of them eating – and anyone who knows me will say that doesn’t sound like me,” the 29-year-old who lives in Kent, England is quoted as saying in a Newcastle University press release about new research into why some people’s brains are sent into overdrive by the sounds of eating or breathing.

When Tansley-Hancock sought help, her family doctor laughed at her and counselling made it worse, she says. So she searched the internet and found the term misophonia.

She’s now part of a research project into discovering why some people are so sensitive to sound. Scientists report the first evidence of clear changes in the structure of the brain’s frontal lobe in those with misophonia in Friday’s edition of Current Biology.

“Misophonia is a condition in which strong negative emotions are triggered by certain specific sounds,” said Sukhbinder Kumar, a research fellow at Newcastle University. Those emotions are usually anger and anxiety, often an intense and immediate fight or flight reaction.

“The commonplace nature of these sounds makes misophonia a devastating disorder for sufferers and their families, and yet nothing is known about the underlying mechanism,” the researchers wrote.

Kumar said many in the medical community are skeptical that misophonia is a genuine disorder and it’s not recognized in any clinical diagnostic schemes. It is still not clear how common the disorder is and there is no clear way of diagnosing it.

To conduct their study, researchers classified sounds into three groups and measured the brain activity of people listening with an MRI. The first group was the trigger sounds of breathing, eating and chewing. The second group included other normally annoying sounds, such as someone screaming or a baby crying. The third group included neutral sounds, such as rainfall or a busy cafe.

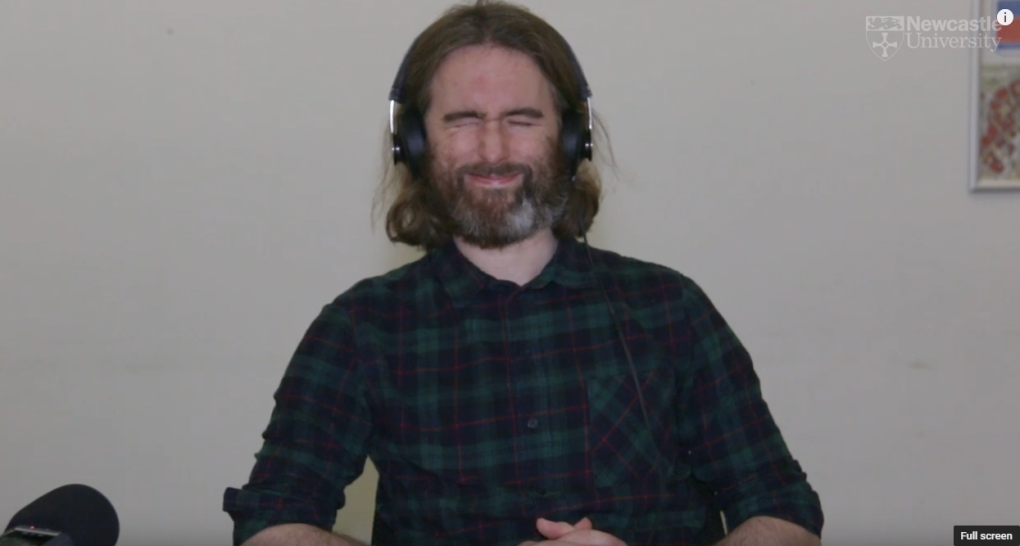

In a video posted to YouTube, test subjects are shown reacting to various sounds. A baby crying garners grimaces, a woman screaming generates wide eyes, but sounds of heavy chewing bring looks of disgust and clenched jaws. One man takes off the headphones with a groan. Researchers found trigger sounds elevated heart rates and sweating in misophonics.

Scientists then looked at the brain activity of those with misophonia while they listened and compared it to those without the condition.

The results were clear, says Kumar. In misophonics, the trigger sounds “evoked a much larger response in the part of the brain called anterior insular.” That part of the brain is involved in processing emotions and integrating signals both from the body and the outside world.

Researchers then discovered that in misophonics the anterior insular is connected in a different way to parts of the brain in the frontal lobe that govern control of emotions than in those without the condition.

Kumar says researchers believe the difference in connectivity is responsible for the “overdrive” reaction in misophonics. He’s hopeful that if he can identify the “brain signature” of the trigger sounds, that it can be used to teach people to self-regulate.

Tim Griffiths, a professor of cognitive neurology at Newcastle University and University College London, said: “I hope this will reassure sufferers.

“I was part of the skeptical community myself until we saw patients in the clinic and understood how strikingly similar the features are.

“We now have evidence to establish the basis for the disorder through the differences in brain control mechanism in misophonia.”

Tansley-Hancock says she copes with her condition through meditation, reduced intake of caffeine and alcohol and by using earplugs.

“This research is a huge relief as it shows there is a physical basis for misophonia which should help others understand the condition. It also opens up the opportunity for better management.”