No matter how much advanced planning is done logistically, there is no way to predict what will happen, editorially, when you show up to cover a story - particularly one as fluid as a sprawling refugee camp spilling well beyond its front gate.

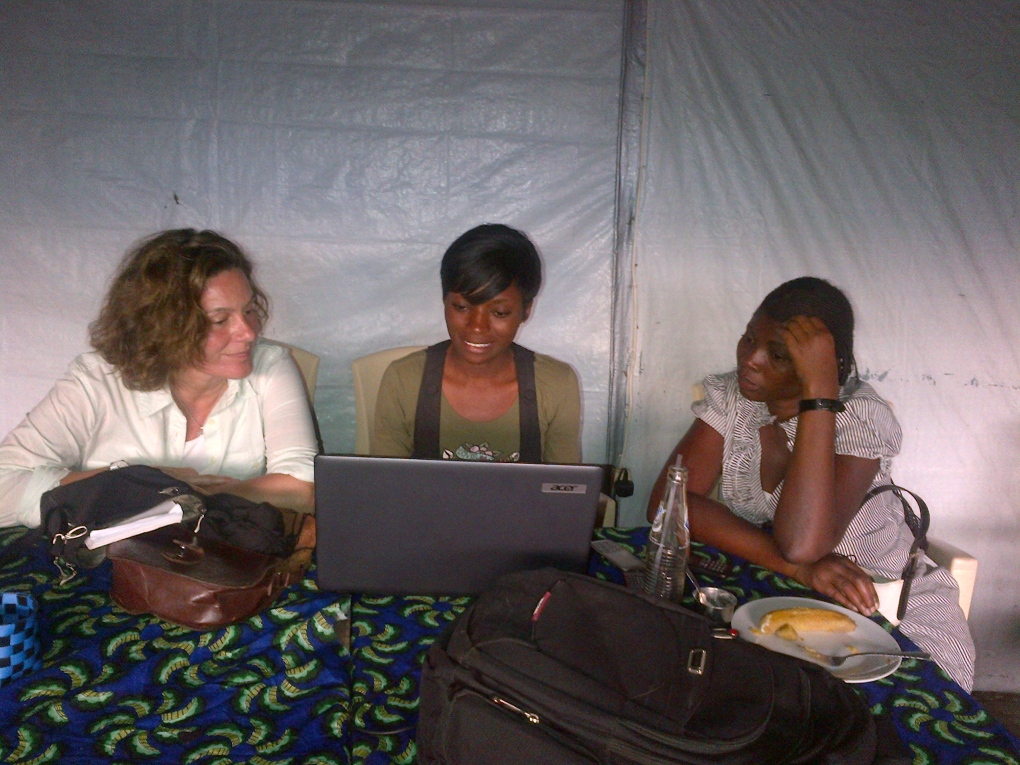

Today the goal was to "job shadow" five young local reporters through a Journalists for Human Rights project here in Goma, DR Congo.

They had their angles in mind:

- investigate the soaring number of rape cases in the camp (58 reported in the last four months)

- probe rumours of "fake refugees" taking advantage of the food distribution program

- discover the truth about accusations of severe food shortages in the camp

Sixteen thousand people live in Camp Mugunga on the outskirts of Goma. It's been here for about a year and is about as close to hell on earth as you could imagine.

It's built on the lava rock that spewed across this entire landscape when the Nyiragongo volcano erupted in 2002, destroying three-quarters of the city.

What is it like?

Imagine a village built on the surface of Mars - in fact, science may show water is more plentiful on the Red Planet than in Camp #3.

Imagine sleeping on this jagged ground in a pup tent with at least eight others - for more than a year and with no end in sight.

Imagine going for firewood behind a row of tents and getting brutally raped by a man in uniform.

Throw in cops that whip crowds of pregnant women jockeying for position in the food line.

It's ugly.

Things seemed ok for the first 20 minutes of this assignment. The reporters fanned out and started interviewing refugees. Almost immediately the subject of food shortages turned into a yelling match among the men who gathered to listen in.

It's important to note that we had full authorization from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to be there, to take pictures and to conduct interviews. For me that quickly went out the window.

A muzungu (a white person) in a crowd of angry, hungry, desperate Congolese and Rwandan refugees, is an obvious target.

Everyone believes a visiting "muzungu" can fix problems, find more food and stop the violence.

They didn't care that I was a journalist. I was "muzungu."

One of the camp's local coordinators tried to intervene by shuffling the "muzungu" into a clearing, but within minutes the crowds starting moving en masse into that clearing with lava rocks in hand.

I watched another cop use a stick to beat the crowds back - pregnant women, barefoot children, fist-clenched men.

About 40 minutes in, JHR Country Director Freddy Mata - who has been a lifeline through this entire journey, a great protector and also a great journalist - looked across the angry crowd at me and said: "It's time to leave. Now."

Accustomed to his mild manner, I knew this directive was urgent.

We made our way through the mobs and into the car that was now surrounded - mostly by children with their hands out, begging for food, money, anything.

I hate leaving a story, but in this case, at this camp, it was clear my role as a trainer for JHR was compromised. I didn't want to become the story - no journalist ever does.

The muzungu pulled out of the camp and the five local reporters were able to stay.

Hours later we met up for a final session to see what they'd uncovered:

- A man admitted he didn't live in the camp, he took the bus in today so he could score some free food on distribution day ("Fake refugees" - tick).

- They interviewed the woman in charge of sexual violence - it's so rampant there's even an association. She confirmed for them that the rapists are mostly military and since January there have been only a small number of police securing the camp because their pay was cut off. (The UN stopped paying police salaries when they asked the Congolese government to pay the tab - the government refused).

- They found out that the food rations, initially intended for one person, were now being split between, on average, six people. And instead of a 15-day distribution plan, it's more like 30 days before the next ration is doled out, they were told. I wasn't able to confirm this myself.

The reporters worked well past the city-imposed curfew to write and report their findings. In this city, because rape is more common than robbery, female reporters often sleep in the newsroom to avoid the risk of walking home.

It's hard to explain the satisfaction a reporter feels when they've filed a great story that can force change, but I saw it tonight in each one of their faces.

This was a difficult day to see firsthand the reality of life for so many victims of this war, but it was also an incredible day to see these young professionals at work.

I am leaving Goma tomorrow, one of the saddest places on earth. Change here will only come from the people themselves - and these five journalists can be (and I'm sure will be) part of that change.

Back to Kinshasa tomorrow.

Lisa