TORONTO -- Revoking a criminal pardon solely on the basis that RCMP have accused a man of plotting to attack a passenger train is unfair and a violation of his right to remain silent, Federal Court heard Monday.

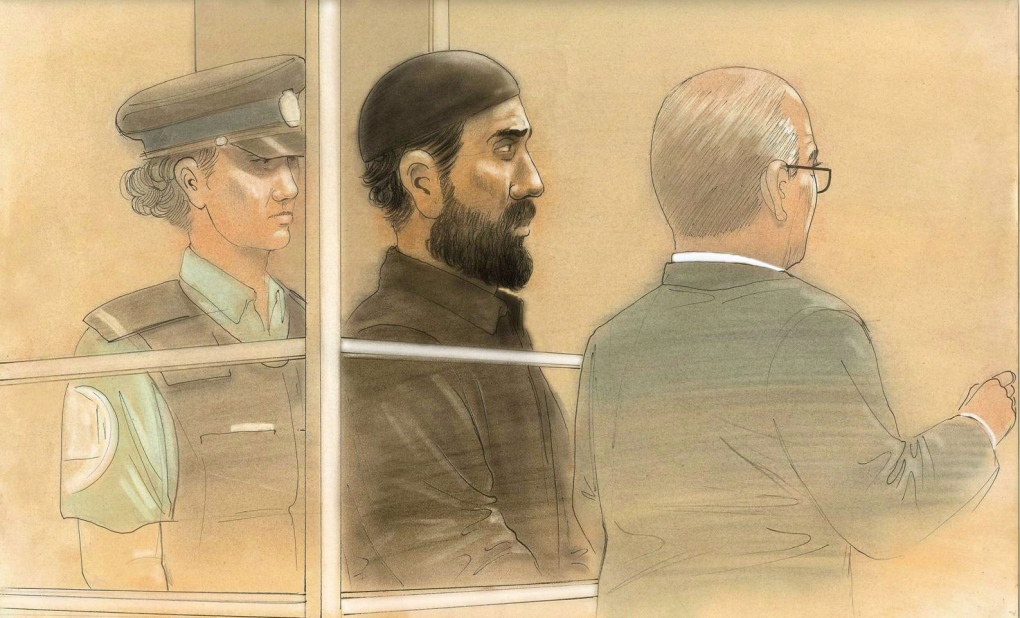

In fact, the lawyer for Raed Jaser argued, legislative provisions allowing a pardon to be set aside on the basis of unproven criminal allegations are unconstitutional.

"Nothing is added by proceeding while the charges are pending," lawyer John Norris told Judge Keith Boswell.

"Not only is there no gain, there is a significant cost."

Evidence of Jaser's criminal record -- if available to the prosecution -- could play a significant role when he stands trial on terrorism-related charges because, for example, it could be used to undermine his credibility.

The Toronto resident, 36, who is in custody pending trial expected to start in late winter, was convicted in 1997 of fraud for passing bad cheques, and in 2001 for uttering threats.

In 2009, the Parole Board of Canada issued him a pardon -- now known as a records suspension -- which it moved swiftly to revoke after he was charged last year along with Chiheb Esseghaier, of Montreal, with an al-Qaida-guided plan to derail a Via or Amtrak passenger train between Toronto and New York City.

When the board told him of its intentions and invited him to argue his case, Norris wrote to say his client would respond to the allegations at trial given his charter right to remain silent.

"Through the board's own motion, it has called upon him to account for the conduct that has led to these serious criminal charges," Norris said.

The board then revoked the pardon, saying Jaser had failed to provide sufficient information to show he continued to be of "good conduct."

Norris called the decision an abuse of process that violated the principles of fundamental justice by using Jaser's silence against him even though he is presumed innocent.

Speaking for the Crown, Michael Sims argued the parole board is an independent agency and the routine administrative proceeding unconnected to the criminal case was not aimed at furthering a police investigation or prosecution.

Jaser's only right was to receive notice of the pending revocation and the opportunity to make submissions on why his pardon should stand, court heard.

"He didn't address what the board was really eliciting comments on, which was that Mr. Jaser was no longer of good conduct," Sims said.

Norris pointed out that the board operates under Public Safety Canada, a "state adversary" in relation to his criminal charges, and there was no reason for the parole board to proceed given that it could still set aside Jaser's pardon even if he is ultimately acquitted. Revocation would be automatic if he's convicted.

"Holding fire, as it were, for the time being would not bring the administration of justice into disrepute," Norris said. "We don't need to move now, because the law will deal with this in due course."

Norris asked Boswell to undo the board's decision, and to strike down the relevant part of the Criminal Records Act. At the very least, he said, the judge should clarify the law to make clear the parole board could not use outstanding criminal charges to justify scrapping a pardon.

Boswell, who reserved his decision, said he was a "big believer" in the right to remain silent.

However, he noted, it can take several years for charges to be resolved and he worried aloud about hampering the parole board in its public-safety mandate.