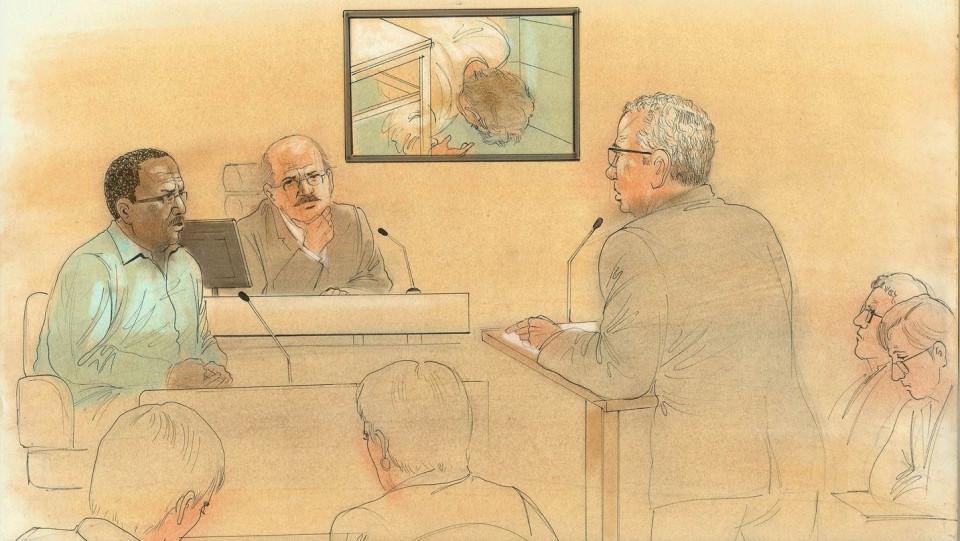

A video showing the last moments of teenage inmate Ashley Smith as she strangled herself to death was shown to jurors Monday at a coroner’s inquest.

The video shows guards and then emergency responders performing chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation after Smith was found unresponsive in her cell at Ontario’s Grand Valley Institution on Oct. 19, 2007.

Smith, clad in a restraint jacket, had strangled herself.

For several minutes, guards can be seen in the video watching Smith’s body, which rested between her steel cot and a wall, and calling out to her.

“It’s been long enough for me to take that off,” a guard yells through the door, referring to the ligature around her neck.

“Sit up so you can come over here and I can cut if off.”

There is no movement in Smith’s cell as the guard continues to call out to her.

At nearly the seven-minute mark of the video, guards enter the cell before quickly calling for a nurse. They also appeal to Smith to “wake up.”

The guards begin attempts to resuscitate her, and try to give her oxygen.

"Are you getting air in?" "No." "Ashley. Come on. Breathe."

Smith’s body is dragged from her cell as paramedics and firefighters arrive. They work on her for half an hour, before she is wheeled away.

The video was shot by a fill-in guard, Valentino (Rudy) Burnett, who was preparing to go home after a night shift.

Burnett told the inquiry that he responded to an all-call for help and was asked to operate a video camera in case guards had to enter Smith’s cell.

Burnett said he did not know Smith’s situation well, but had been told by other guards that she was a “problematic inmate.” He also said he had once seen guards drag Smith from an interview room with something tied around her neck.

He said he was not given any instructions for what to do in the event that he observed such an incident.

Smith, originally from Moncton, N.B., had arrived at Grand Valley on Aug. 31, 2007, and was placed in segregation right away. She remained there until her death.

Smith was first arrested at age 13 for assault and causing a disturbance, and was jailed at 15 after throwing crab apples at a postman. Her time in the federal prison system was marked by repeated incidents of self-harm.

Last November, Canada’s corrections watchdog said after reviewing videos related to Smith’s case, he found the teen to have been involved in a total of 160 “use of force” incidents during her 11-and-a-half months in federal custody. Videos previously shown at the inquiry show Smith in restraints and being tranquilized against her will.

Earlier Monday, an assistant warden at Grand Valley who had led a jury tour of the facility last week, answered questions about the institution, specifically about Smith’s cell.

Julian Falconer, a lawyer representing Smith’s family at the inquiry, asked Tony Simoes about the steel cot Smith slept on.

"There can be legitimate security reasons for making people sleep on metal?" Falconer asked.

"Is sleep deprivation part of (Correctional Service of Canada) punishment?"

"I cannot comment on that," Simoes responded.

"You don't know?"

Simoes said he could not answer questions about potential sleep-deprivation tactics.

The inquiry also saw photographs of the exercise yard for inmates in segregation, a concrete box topped with barbed wire measuring three metres by 10.5 metres.

Who was Ashley Smith?

Smith was a 19-year-old inmate at the Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ont. who strangled herself in her cell on Oct. 19, 2007.

Growing up in Moncton, N.B., Smith was a troubled child who first got arrested at age 13 for assault and causing a disturbance.

Why was she in custody?

At 15, Smith was sent to jail for throwing crab apples at a mail carrier. Once in the prison system, Smith often harmed herself and racked up numerous offences that kept her in jail. She was transferred in and out of nine institutions in five provinces before ending up at Grand Valley.

Why is there a second inquest?

The first inquest, under Dr. Bonita Porter, began in May 2011, but was marred by legal and procedural challenges. When Porter announced her retirement, another coroner was found to replace her, but the inquest was formally terminated later that year.

What does the coroner’s inquest hope to achieve?

The presiding coroner of the second inquest, Dr. John Carlisle, said the probe should help shape policies and procedures at correctional facilities. He also told the jury that the inquest is “the best memorial we can give to Ashley.”

With files from The Canadian Press