Almost immediately after a runaway train derailed in Quebec over the weekend, the blame game began, with the head of the company blaming firefighters for shutting off the locomotive and thereby causing the brakes to fail, and firefighters saying they were just doing their job.

Allan Bonner, an expert in crisis management communication and the author of An Ounce of Prevention, says there are valuable lessons to be learned from the way the crisis has been handled by all sides.

Here are some of Bonner's key tips and lessons learned from the disaster:

Don't blame anyone in the early days

It may be true that firefighters shut down the locomotive, thereby causing the train's air brakes to release. But as of yet, that isn't a confirmed fact. And it's just one of many details that will be revealed over the course of multiple investigations.

Don't rush to lay the blame on someone else, Bonner says.

"What firefighter did is put out the fire. And perhaps they incorrectly turned of the gizmo that keeps the brakes running. But (MMA chairman Edward Burkhardt) owns the train, he could have had someone there to make sure in an emergency like that the train doesn't run away or he could have had a barrier -- who knows what. These are the mistakes made over and over again, it's very frustrating."

'Look like you belong there'

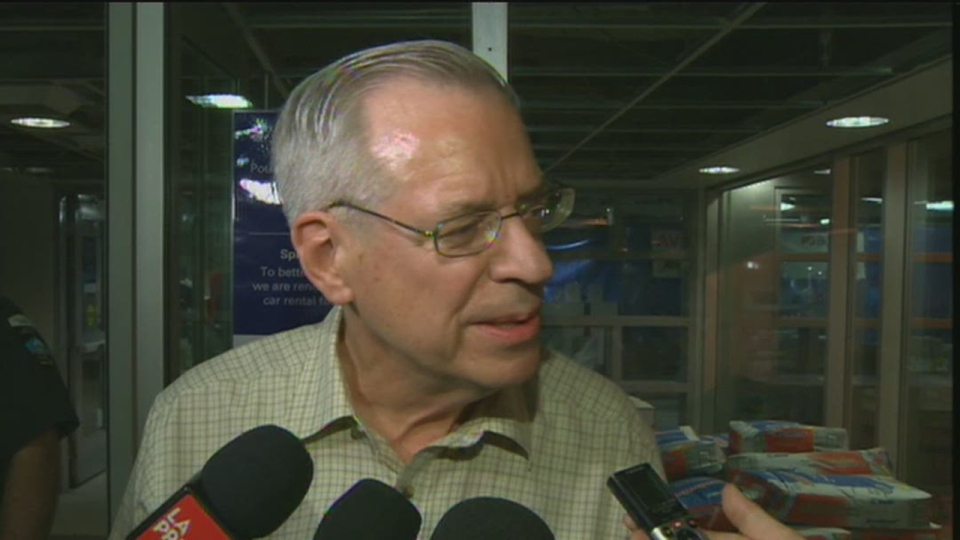

When Burkhardt, chairman of Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railways Inc., arrived at the Montreal airport on Tuesday night, he appeared surprised and unprepared to speak to the media who were ready to bombard him with questions. In fact, Burkhardt initially appeared to avoid reporters, before giving in and holding an impromptu news conference.

Bonner said a company leader who decides to go to the scene of a disaster must be prepared and in control of the situation, and ready to face the media -- on his or her own terms.

"This is a 74-year-old man who just got off the airplane and did a 15-minute scrum in the Montreal airport. I wouldn't advise anyone to do that of any age on any topic: it is too long, you cannot sustain that discussion, you get into wild speculation," Bonner said. "He should have made a statement or, better yet, got to Lac-Megantic privately."

Make a firm decision about whether to go to the location, and stick to it

"The debate about whether a CEO goes is an ongoing debate; you're damned if you do, you're damned if you don't," Bonner said.

He added that Burkhardt is a businessman and likely has little experience or expertise cleaning up a disaster scene, and likely would have been more effective working from his Chicago office as he did for the first four or five days after the accident.

"These people are where they are because they're good businesspeople, but they don't act as their own lawyers, if they're not a lawyer. And they should get the advice or hire someone who's a good spokesperson because this is a very important aspect of crisis management -- to calm people down, reduce liability, exhibit due diligence and on it goes."

However, from a public relations perspective, he said it often makes sense for the head of a company to go to the scene of a disaster and appear to deal with the issues face to face.