The head of the Assembly of First Nations is calling on Prime Minister Stephen Harper to make things right and improve funding for aboriginal child welfare in the wake of shocking revelations about nutritional experiments done on hungry children several decades ago.

Shawn Atleo says the federal government needs to work with First Nations to address what was done in the past and help ensure that aboriginal families today have access to healthy food.

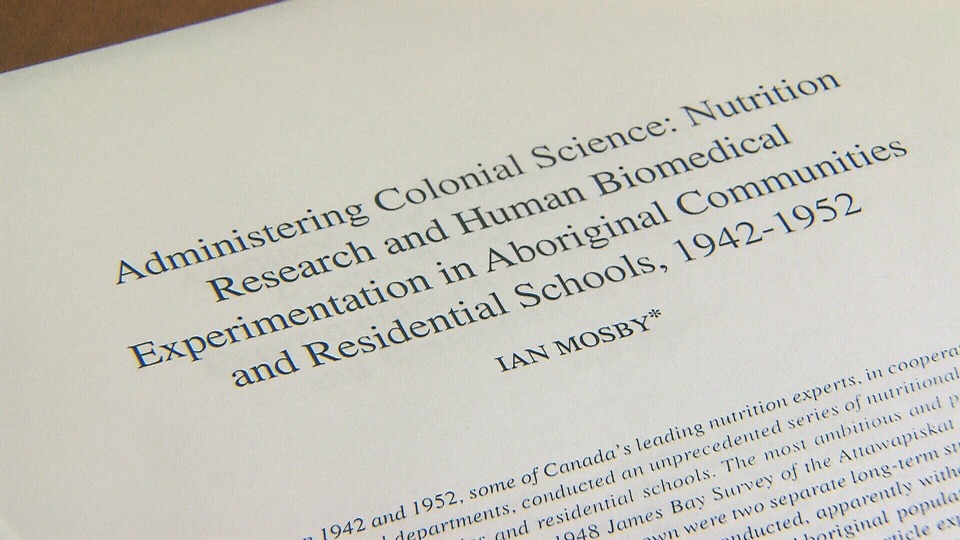

Recently published research by food historian Ian Mosby revealed that Canadian government researchers used hungry aboriginal children and adults in nutritional experiments in the 1940s and 1950s.

Starving people and kids became unwitting subjects in tests involving vitamins, minerals and caloric intakes. Nutritional supplements were given to some, but not to others to see how a starvation diet affects the body. Milk rations were kept low at one residential school and dental work was withheld from some children to determine the study’s effects on gums and teeth.

“Our children were literally lab rats for the most unconscionable, horrific testing,” Atleo said, adding that his own father was among the “lab rats” at a residential school in British Columbia.

The federal government released a statement saying it’s looking into the matter.

“If this story is true, it is abhorrent and completely unacceptable,” the statement said.

Mosby, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Guelph in Ontario, wrote in his paper that nutritional tests were conducted between 1942 and 1952 on northern Manitoba reserves and at six residential schools across Canada.

In the end, at least 1,300 aboriginals, most of them children, were involved in the experiments, Mosby’s report said.

But Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, whose own relatives were subjected to nutritional tests, says the number is likely much higher.

“It’s very likely this was a national program that involved tens of thousands aboriginal students, aboriginal peoples, aboriginal communities,” he said.

The experiments were conducted during the height of the Second World War and have drawn comparisons to inhumane tests done by Nazis.

Atleo and other critics point out that many First Nations children still live in poverty and often don’t have access to basic food items, such as fresh food and vegetables.

Systemic malnutrition still persists on northern reserves, where a jug of milk can cost $20 and junk food is usually cheapest.

With a report from CTV's Winnipeg Bureau Chief Jill Macyshon and files from The Canadian Press